13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(8):4042-4057. doi:10.7150/thno.127053 This issue Cite

Review

From 2D cultures to 3D systems: evolving cancer models at the interface of functional precision medicine and theranostics

1. Department of Pathology and Neuropathology, University Hospital and Comprehensive Cancer Center Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

2. Werner Siemens Imaging Center, Department of Preclinical Imaging and Radiopharmacy, University of Tübingen, Germany.

3. Cluster of Excellence iFIT (EXC 2180) "Image-guided and Functionally Instructed Tumor Therapies", University of Tübingen, Germany.

*Joint first authors

#joint senior authors.

Received 2025-10-21; Accepted 2025-12-27; Published 2026-1-21

Abstract

Advances in patient-derived cancer models are pushing precision oncology by linking functional testing directly to therapeutic decision-making. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cancer cell culture systems have long served as accessible tools for studying cancer biology and drug responses, but their inability to replicate the complexity of the tumor microenvironment limits their translational value. In recent years, advances in culture and imaging technologies have enabled the development of three-dimensional (3D) cancer models, such as spheroids, organoids, and patient-derived explants, that more accurately represent tumor architecture and behavior in vivo. These models better capture cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions and allow to study immune-tumor dynamics, providing critical insights into therapeutic efficacy and drug resistance of chemotherapies, targeted therapies, and immunotherapies. Notably, the integration of 3D modeling with functional precision medicine approaches, such as ex vivo drug screening using patient-derived samples, has opened new avenues for individualized cancer treatment. Coupling these advanced models with advanced imaging readouts for spatially resolved and functional analysis further transforms them into quantitative theranostic platforms that link biological mechanisms to clinical decision-making. In this review, we explore the evolution from 2D to 3D cancer models, examine their respective advantages and limitations, and highlight their role in advancing functional precision oncology and immuno-theranostics.

Keywords: functional precision medicine, cell culture, spheroids, organoids, cancer-on-a-chip, tumor explants, PDX, tumor microenvironment

Introduction

Cancer is a long-lasting global health challenge and the gap between preclinical promise and clinical benefit remains large [1,2]. One reason for this is the fact that most of the commonly used models do not replicate the cellular heterogeneity, spatial organization, and dynamic signal transduction of the human tumor microenvironment (TME), conflating treatment response. In addition to this, the TME is significantly influenced by mechanobiological factors, including extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness, physical confinement, and shear stress from fluid flow. These mechanical drivers are responsible for the migration of cancer cells; immune-cell trafficking; delivery of foreign products, including drugs; and for the development of treatment resistant TMEs [3-6]. These considerations are particularly relevant when selecting experimental models since 2D cultures, 3D matrices, organoids, tissue slices, and microfluidic systems each vary significantly in their ability to recapitulate physiologically relevant mechanical contexts. For that reason, treatments that appear appealing in vitro or in animal models are often poorly reported in patients. This inspires a renewed emphasis on models that retain better the native human tumor biology [7,8].

Over the last ten years, 3D culture systems, such as spheroids, organoids, scaffold-based constructs, microfluidic cancer-on-chip platforms and patient-derived xenografts (PDX), have expanded our toolbox. Each model represents a balancing act that involves scalability, biological realism, and translational applicability. However, none by itself can fully recapitulate the intact human TME with its stromal, vascular and immune constituents arranged in native architecture. Importantly, this limitation is particularly consequential for immuno-oncology, since the spatial context and quality of immune-tumor interactions are pivotal.

Functional Precision Medicine (FPM) is a developing aspect of personalized oncology seeking to match patients with a more potent regimen of drugs through testing the drug on their own tumor cells [9]. In contrast to previous precision medicine approaches based on genomic profiling of patients and predicting drug sensitivity, FPM assesses the real-time functional behavior of living cancer cells when exposed to therapeutic agents [9,10]. This enables direct assessment of drug effectiveness in clinically relevant patient scenarios, particularly when genomic alterations are absent or non-actionable.

Among the crucial factors making FPM successful is the development of biologically relevant culture systems or cancer models for cancer. HeLa cells were isolated as the first immortalized human cancer cell line in 1951 and transformed the field of in vitro cancer studies [11]. Since then, 2D cell cultures have evolved as cost-effective and important instruments of exploration of basic cancer biology, drug discovery, and molecular pathway detection with the help of model constructs [12]. These models have been used in the investigation of cancer cell behavior and to research potential therapies in lab-controlled microenvironments. Nonetheless, their intrinsic simplicity has considerable drawbacks, since simplistic models struggle to mimic the 3D geometry and complex TME including interactions of the cell-cell and cell-ECM [12,13]. More complex cancer models such as tumor spheroids, organoids, cancer-on-a-chip systems, and bioreactors better mimic from duplicating cancer complexity in the TME as well as cellular interactions within the TME. With 3D culture systems that can also adopt patient-specific features of the TME, such as patient-derived organoids (PDOs) and patient-derived tissue slice cultures, these technologies have become valuable assets for personalized medicine [13]. Moreover, PDX models are commonly used to serve as in vivo 3D models for drug screening and mechanistic studies [14]. However, PDX models are also limited in their clinical applicability because engraftment and expansion require weeks to months, which is too slow for many treatment-decision timelines [15]. The species-specific immune cellular components and metabolic differences could also reduce the accuracy of prediction [16].

This review discusses the current state of science of cancer models within FPM context, including their increasing significance within immuno-oncology and theranostic applications. We describe conventional 2D and 3D culture systems in order to compare strengths and limitations, and discuss recent developments in patient-derived tissue explants and dynamic culture platforms that can directly assess therapeutic and immune responses within a preserved TME. Additionally, we demonstrate to what extent spatially resolved and dynamic analytical modalities, such as live microscopy and multiplex tissue imaging, can complement these models, connecting molecular mechanisms with therapeutic efficacy in situ. No model is ever perfect, but there are systems now in practice which can facilitate the selection of the most appropriate approach for the biological question or clinical decision. Together, these developments emphasize the extent to which advanced cancer models are changing the interface between experimental studies and clinical decision-making to a theranostic field, one that integrates functional testing, mechanistic knowledge and individualized therapeutic planning within one experimental framework.

Functional Precision Medicine

Accurately predicting cancer behavior requires not only static genomic, proteomic, and metabolic profiles but also an understanding of how these components interact across different cellular states [17]. While genomic profiling reveals accumulated mutations, it does not capture dynamic functional responses [18]. FPM, which tests live patient-derived materials, provides more direct and actionable insight into therapeutic sensitivities and has shown clinical value, particularly for patients without actionable mutations or those resistant to standard therapies [19]. As immuno-oncology advances, models that incorporate interactions between tumor and immune cells enable the evaluation of checkpoint inhibitors, adoptive cell therapies, and vaccines under near-physiologic conditions, expanding FPM from drug-response testing to predictive immune theranostics.

The idea of FPM originated decades ago with assays that exposed patient-derived samples to drugs and measured cell death, initially focusing mainly on hematologic cancers [20-22]. Advances in culture systems have since expanded FPM from simple drug-sensitivity testing to evaluating TME influences, immune interactions, and therapy-induced cellular changes [23,24]. Modern platforms integrate immune-competent co-cultures, tumor explants, and functional assays such as dynamic BH3 protein profiling and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assays to characterize drug-induced apoptotic priming and treatment-associated cytotoxic responses [25-27]. Integration of multimodal data, supported by artificial intelligence (AI)-driven analysis, now enables biomarker discovery and therapeutic target identification that can be validated in patient-derived models, positioning FPM firmly within the theranostic framework [28,29]. In parallel, advances in machine learning enable automated analysis of high-content imaging, single-cell phenotyping, and complex drug response patterns. Integrative models that combine multiomics, clinical, and biological data enhance patient stratification and improve predictions of disease progression, treatment response, and risk, thereby increasing the clinical utility of FPM platforms [30,31].

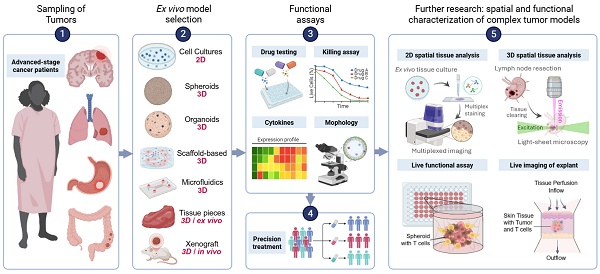

A standard FPM workflow consists of patient enrollment, tumor sampling and generation of patient-derived 2D or 3D models for drug sensitivity testing, with results being integrated alongside clinical and molecular data and reviewed by an FPM tumor board. More recent pipelines leverage sophisticated 3D and tissue-explant systems to better preserve the TME and immune context. Microfluidic or perfused bioreactors also contribute to maintenance of immune-tumor interactions and support longitudinal functional readouts. Ultimately the effectiveness of FPM is assessed through iterative comparison of model predictions with patient outcomes (Figure 1).

As functional assays diversify, the choice of model system becomes central to both technical feasibility and diagnostic relevance. In a theranostic context, the model itself serves as a biosensor, translating biological complexity into measurable treatment response. The following sections therefore compare available model formats and illustrate how their design, ranging from simple 2D cultures to dynamic explant bioreactors, determines their suitability for personalized therapy and immuno-oncology applications.

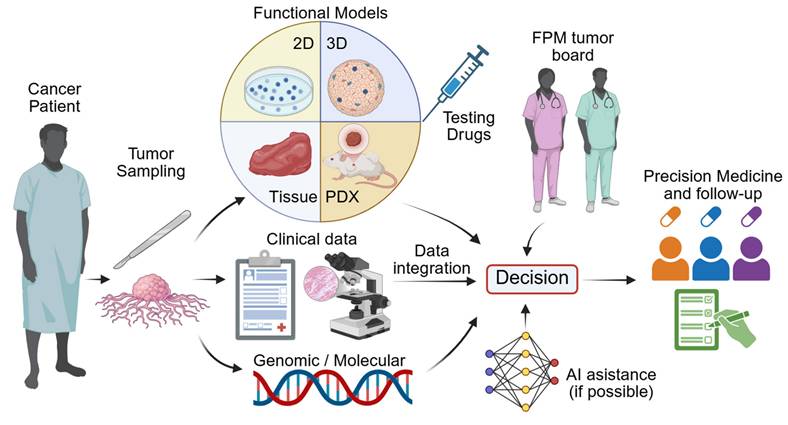

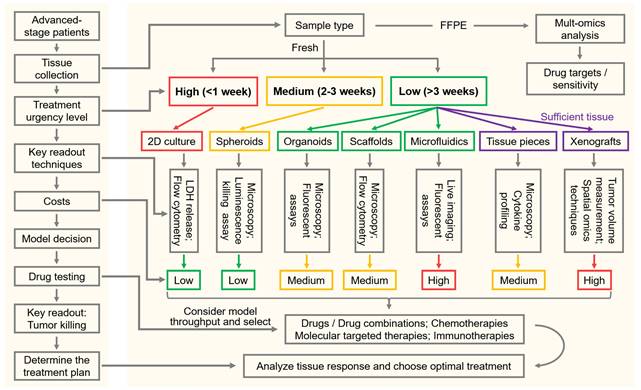

FPM in Cancer Management. Generally, advanced-stage cancer patients enroll at treatment centers, and tumor tissue is collected via surgery or biopsy. Following that, the functional models are then selected according to tumor type and urgency of treatment. The FPM tumor board reviews drug sensitivity results along clinical and genomic data with AI assistance to guide precision therapy and follow-up.

Patient-Derived Cancer Models for Drug Sensitivity Evaluation

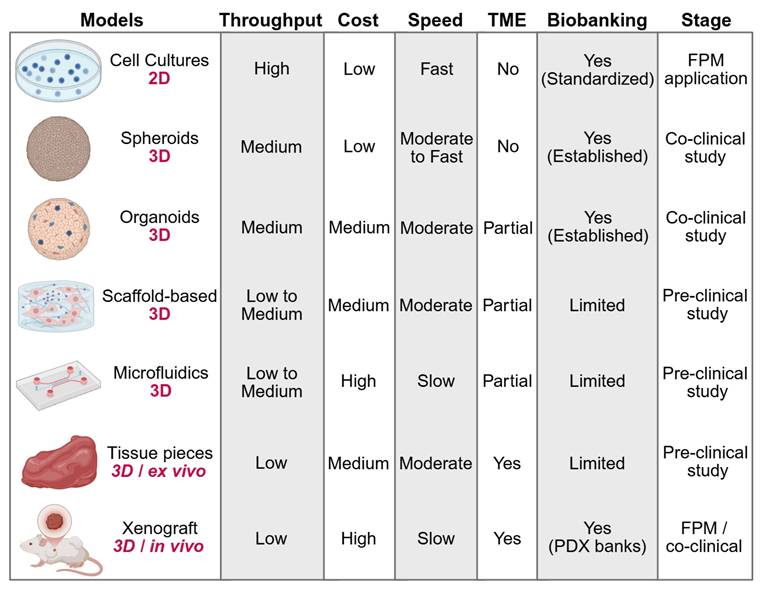

The evolution of various cancer models has helped FPM by allowing direct measures of patient-specific drug responses. Its cost, throughput, speed, and preservation of TME characteristics vary for each model, influencing its application in different clinical settings. In immuno-oncology, these properties also determine whether a model is capable of sustaining meaningful interactions between tumor, stromal and immune compartments, which is a prerequisite for evaluating checkpoint blockade, adoptive cell transfer or cytokine-modulating therapies. 2D cultures are still fast, cost-effective, but have operationally straightforward nature, thus aiding in timely clinical decisions in FPM pipelines. Nevertheless, due to their low structural complexity and lack of immune context their applicability is restricted to either cytotoxic or targeted-agent screening purposes. By contrast, 3D models better mimic both tumor architecture and heterogeneity and yield accurate therapy predictions. By combining various cell types together and sustaining spatial gradients, 3D models also support immune infiltration and drug distribution, which are increasingly important parameters of immuno-oncology testing and theranostic assay development. While their costs, complexity, and longer duration can restrict their applications in the clinic and they are valuable tools for mechanistic finding, biomarker discovery and selective FPM applications [19]. We compare these models and describe their advantages and disadvantages, as illustrated in Figure 2, Table 1 and also given in the following text, and how they help to influence FPM. Particular emphasis is added to new patient-derived 3D systems, such as organoids, explants, and perfused cultures, which link mechanistic research and clinical decision-making and represent the way in which cancer modeling is advancing into a theranostic field.

2D cell culture

2D monolayer cultures remain the simplest and most widely used patient-derived cancer models. They are inexpensive and suitable for large-scale drug screening but inherently lack the 3D architecture, stromal signaling, and immune context that shape real tumor responses [28]. This loss of microenvironmental signaling can limit their predictive accuracy for complex tumor behaviors, including metabolic dependencies and interactions with stromal or immune cells, and may underestimate drug resistance mechanisms that depend on tissue architecture [32]. Moreover, inconsistent isolation procedures and low culture initiation success rates hamper the reproducibility of 2D cultures [33].

Comparison of Cancer Models for FPM. Models are compared by dimensionality, throughput, cost, culture speed, TME preservation, biobanking potential, and stage of clinical application. The FPM application stage indicates models used to directly inform patient treatment decisions. The co-clinical study stage refers to models used alongside standard patient treatment to evaluate therapeutic responses. The preclinical study stage includes models used for basic and translational research. Additional study details are provided in Table 1.

Suspension-based 2D models were initially developed for hematological malignancies, where tumor cells naturally exist as single-cell suspensions compatible with high-throughput drug screening [29,34]. Several clinical studies have demonstrated that such functional testing can guide therapy selection and improve outcomes in relapsed or refractory leukemia and lymphoma patients [22,35]. In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which included 78 relapsed and 41 refractory cases, 2D suspension cultures were used for screening 515 drugs, which promoted clinical response in 59% of patients that received treatment including 45% complete remission [36] (Table 1). Suspension-based 2D models in hematologic cancers are gaining popularity in the clinic, and there is increasing evidence that they can be used in FPM on a regular basis [22,36,37].

Likewise, monolayer 2D cultures are among the most technically accessible models for studying solid tumors in FPM. Several clinical studies have demonstrated their utility in predicting therapeutic responses [10] (Table 1). As example, in one large-scale study involving 568 tumor biopsies from various solid cancer types, drug sensitivity was quantified using 2D monolayer cultures with 6 tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and the observed sensitivities were found to reflect actual clinical responses [38]. Thus, despite their simplicity, 2D monolayer models remain relevant and effective tools for rapid, cost-effective screening in FPM, although their lack of microenvironmental context remains an important limitation to consider when interpreting results.

3D spheroids

3D spheroids are widely recognized as one of the earliest and most fundamental forms of 3D cell culture. Cells in spheroids aggregate and interact in all three dimensions. Although most spheroid models lack the cellular heterogeneity and architectural complexity of native tumor tissues, they were developed to overcome the limitations of traditional 2D cultures. Spheroids better mimic critical tumor characteristics, including cell-cell interactions, oxygen gradients, drug penetration, and resistance patterns [39,40]. Such properties are of paramount importance in the field of FPM for more accurately predicting therapeutic responses. When co-cultured with autologous immune or stromal cells, spheroids can also recapitulate immune cell infiltration and cytokine signaling, providing a simple but useful assay for immunotherapy evaluation.

Beyond conventional low-adhesion and hanging-drop techniques, emerging material-engineering approaches based on liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) offer new strategies for controlling spheroid formation. LLPS, a process in which a homogeneous mixture separates into distinct liquid phases, has been recognized in biological systems as a mechanism for organizing non-membrane cellular compartments and coordinating biochemical processes. When applied to soft material engineering, LLPS-based systems enable customizable microenvironments that support controlled cellular organization and may facilitate the generation of more physiologically relevant spheroid structures for cancer modeling [41].

Spheroids, as the simplest, most cost-effective, and rapid-to-establish 3D cancer models, are widely used in clinical FPM studies. Their ability to better mimic the tumor architecture compared to 2D cultures makes them valuable for drug sensitivity testing. In a lung cancer study, cancer spheroids generated from 20 patient biopsies were used to evaluate responses to 6 tyrosine kinase inhibitors, achieving a strong predictive accuracy of 85% in co-clinical trials [42] (Table 1). In another study involving 44 newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients, drug testing with six chemotherapy agents based on 3D spheroids reached an overall prediction accuracy of 89% [43]. Collectively, these studies position spheroids as a practical bridge between high-throughput drug screening and more advanced patient-derived 3D or ex vivo systems, although the absence of an TME constrains their relevance for immunotherapy evaluation.

Organoids

Organoids have greater structural and biological complexity compared to spheroids, preserving the histological, genetic, and phenotypic features of the original tumor and their ability to self-organize into tissue-like structures. Long-term expansion is maintained and they can incorporate multiple cell types, which better resemble the heterogeneous TME [44]. This complexity allows the examination of immunotherapies that depend on the interaction of immune and cancer cells [45]. Such characteristics further promote the accuracy of clinical drug response prediction, improve the modeling of tumor heterogeneity, and offer a basis for personalized treatment strategies with higher translational relevance.

Recent work has also contributed to the development of PDOs as a central instrument in FPM. Novel investigations suggest a transition from genomics-only guidance toward ex vivo functional testing on living patient-derived tumor models, including PDOs, directly exposed to therapeutics to characterize patient-driven responses [46]. Meanwhile, recent developments in biofabrication and organoid-microfluidic system integration have yielded a number of cancer-on-a-chip platforms capable of more closely mimicking the complexity of TME and to conduct high-content assessment of therapeutic effectiveness [47]. Together, these advances have highlighted a growing place for PDO-based systems in next-generation cancer modeling and personalized therapy design.

PDOs have also recently emerged as powerful co-clinical models for the analysis of functional drugs for solid tumors because they recapitulate important features of patient tumors. In a study on metastatic gastrointestinal cancers, 29 biopsy samples from 21 patients were used to generate organoids and screen 55 drugs, achieving a high predictive accuracy with 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity [48]. Similarly, in breast cancer, PDOs derived from 35 patients were tested on a panel of 49 drugs that included immunotherapies, achieving 82.35% sensitivity and 69.23% specificity to predict clinical response [49] (Table 1). Currently, due to their broad application and extensive study, PDOs show strong potential to become the most widely used 3D model for FPM. Their compatibility with imaging, omics, and multiplex profiling further positions PDOs as a central model of emerging theranostic workflows.

Scaffold-based cancer models

3D culture systems based on scaffolds fall under the category of 3D models that include physical frameworks to help and organize cell growth. Scaffold-based systems deliver superior mechanical support, a clear architecture, and much higher reproducibility [50]. Several scaffold types have been established, all of which have their advantages: synthetic polymer scaffolds are easily adaptable and are suitable for large-scale manufacture, but surface coatings are necessary for better biocompatibility, hydrogels imitate ECM characteristics and facilitate cell viability, and decellularized scaffolds retain native tissue architecture and allow cell function [51]. Few significant limitations also appear. Natural polymer scaffolds have significant batch-to-batch variability as well as immune response induction. By comparison, synthetic degradable polymers result in more uniform consistency, but have potential to impair biocompatibility as cytotoxic degradation products can arise and also have limited support for their native cell functions. Hydrogels, while tunable, often have low mechanical strength and long-term stability. Decellularized tissues also experience issues with availability, substantial batch-to-batch variation, and residual xenogenic components which compromise the reproducibility and translational reliability [51]. These models nevertheless represent a unique recapitulation of the structural TME and are useful for studies where biomechanical characteristics of the tissue are of benefit. Scaffold systems can further model gradients of cytokines or cell distributions that are also relevant in studies on immune exclusion and mechanical mechanisms of immune cell trafficking in tissues, when seeded with immune or endothelial cells [52,53].

Currently, scaffold-based cancer models are primarily investigated in the fields of materials development and preclinical research. These systems show considerable promise in evaluating patient-specific drug responses across various tumor types. For instance, polymer scaffold based models for breast cancer and hydrogel based models for prostate cancer have demonstrated the feasibility of drug screening in a personalized context [54,55]. In colorectal cancer , decellularized tissue scaffold-based cancer models constructed from 23 patient samples were used to assess responses to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or FOLFIRI (folinic acid, fluorouracil, and irinotecan), providing a patient-specific platform for functional drug evaluation [56] (Table 1). Collectively, these studies highlight the potential of scaffold-based systems in advancing functional precision oncology. By combining mechanical tunability with cellular complexity, scaffold platforms may serve as modular components of hybrid 3D ex vivo systems, bridging material science and (immuno-) oncology within a theranostic framework.

Cancer-on-a-chip

Cancer-on-a-Chip (CoC) is an in vitro model based on microfluidics which is developed to more accurately mimic the TME. The challenges of such systems include a lack of standardization, high cost, and low throughput, but also bring advantages in a different way. Their underlying principle is based on fluid flow to create shear stress, oxygen gradients, and controlled nutrient delivery in a way that imitates the physical, chemical, and biological environment of cancer tissues in a controlled, small-scale fashion [57,58]. The combination of the patient-derived cells with the ECM provides the means for monitoring the performance of real-time cell behavior, how cells interact and are activated or inhibited by drugs to identify and control behavior and drug response. Some of those more sophisticated models have the capability to incorporate multiple organ-like compartments on a single chip, thus making these models valuable for basic studies and FPM application in specific applications [57]. For immuno-oncology, CoC systems allow spatial separation of immune and tumor compartments connected by microchannels, permitting quantitative analysis of immune-cell migration, tumor infiltration, and cytokine gradients under defined flow conditions [59], which is an emerging frontier for functional immunotherapy testing.

Nonetheless, while still in its infancy, CoC technology is proceeding fast, underscoring its potential for personalized immunotherapy in increasing numbers of new studies. For instance, in a preclinical breast cancer study conducted from 2 breast cancer patients' samples, a CoC was used to measure CAR-T cell therapy, facilitating a target dose-response assessment on an individual basis for both efficacy and safety [60]. Similarly, a trial of 12 lung cancer patients utilizing CoC to model anti-PD-1 immunotherapy enabled us to evaluate patient-specific drug response [61] (Table 1). These proof of concept studies demonstrate how CoC technologies can be developed into miniaturized theranostic devices for the application of real-time, immune-competent drug testing.

Although microfluidic platforms can improve microenvironmental regulation at the level of microenvironment, they possess small tissue masses. To preserve native tumor architecture and immune cell assembly on a greater scale, ex vivo tumor explants and perfusion-culture bioreactor technologies, which maintain spatio-functional integrity of patient tissue and facilitate dynamic therapy evaluation have been investigated.

Tumor explants

Tumor explant cultures, consisting of small tissue fragments and slices, narrow the divide between in vitro and in vivo models by preserving the native tumor architecture and cellular composition of the TME. By preserving innate cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions, such cultures maintain essential spatial relationships among cancer, stromal, and immune cells that are otherwise lost during tissue dissociation [62]. Tumor tissues are normally cut into small fragments or thin slices to improve viability and oxygenation, which act as a pathway to nutrient diffusion and waste removal. Nevertheless, in conventional static cultures that are only temporarily viable, the gradients of oxygen and nutrients result in progressive cell death and loss of immune function.

To address these restrictions, perfusion-based culture systems are fabricated for continuous circulation of medium throughout or across the tissue. These bioreactor platforms prolong culture duration from days to weeks while preserving tissue morphology, metabolic activity, and immune competence [63,64]. The system has varied from basic microfluidic flow-through platforms to perfusion bioreactors, which trade throughput with the need for physiological fidelity in the system. Perfused explants have also been extensively applied for evaluation of chemotherapy, targeted therapy and immunotherapy responses for various tumor types including glioblastoma, pancreatic cancer and lymphoma [62,65,66].

In immuno-oncology, perfused tumor and lymphoid explants offer a unique opportunity to evaluate checkpoint inhibitors, CAR T cells, or oncolytic viruses in the patient's TME. Studies in glioblastoma and melanoma have revealed that both ex vivo immune activation and T cell infiltration patterns observed in perfused explants correlate with clinical response [62,67]. Imaging T cell migration and tumor cell killing in real time, within such systems, adds a mechanistic layer linking immune dynamics to therapeutic outcome.

Consequently, from a theranostic point of view, the perfused tissue models have emerged as living diagnostic devices that generate clinically relevant functional information on therapy efficacy and provide molecular data for biomarker discovery. Their capacity to extract patient-specific readouts within actionable timelines renders them an exciting tool for the FPM pipeline, complementing organoids and xenografts rather than displacing them.

Xenografts

Whereas perfused tumor explants allow for the viability of human tissue beyond the body, PDX represent their in vivo counterpart where patient tissue is engrafted into immunodeficient mice to study tumor growth and therapy response under systemic physiological conditions [68,69]. PDX models are a unique in vivo platform to explore drug distribution, metabolism, elimination, and toxicity. By accurately simulating the native tumor biology and treatment response, these models provide valuable insights [14,19].

Humanized PDX systems allow the reconstitution of human immune components in the host mouse and, with that, partial modeling of tumor-immune interactions. These features render them especially important for preclinical immunotherapy studies that can be used for the screening of immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T cell therapies, or combination regimens in a human-like immune context [70].

However, the lengthy engraftment process, high cost, variable success rates, and ethical concerns limit the feasibility of PDX models for routine clinical application in FPM [71]. Nevertheless, PDX models are an important way to analyze drug sensitivity and to investigate the mechanism of drug resistance, providing a viable in vivo platform for validation of new therapeutics and drug delivery strategies. In gallbladder cancer, a clinical study involving 12 patients demonstrated that PDX-guided chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival and disease-free survival [72]. Similarly, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, a cohort of 49 PDX models was used to evaluate individual responses to cetuximab [73] (Table 1). To enhance their translational application in FPM, future efforts should focus on optimizing and standardizing PDX workflows to better meet clinical demands.

Spatial and functional readouts for theranostic applications

With increasingly sophisticated model systems available, equal attention must be given to the technologies that are used to extract meaningful data from these models. As the complexity of 3D and ex vivo culture strategies increases, advancements in technologies to quantify spatial and functional parameters of (immune) cell response in tumor tissues have been made [74,75]. High-content microscopy, multiplex immunofluorescence, and spatial transcriptomics now permit quantitative mapping of drug responses within intact tissues [76-78]. Such approaches show spatial heterogeneity, for example differential drug penetration, localized apoptosis, or immune exclusion, that bulk assays cannot capture. In combination with confocal or multiphoton time-lapse imaging, they allow visualization of dynamic phenomena, such as immune-cell trafficking and tumor-cell killing in real time.

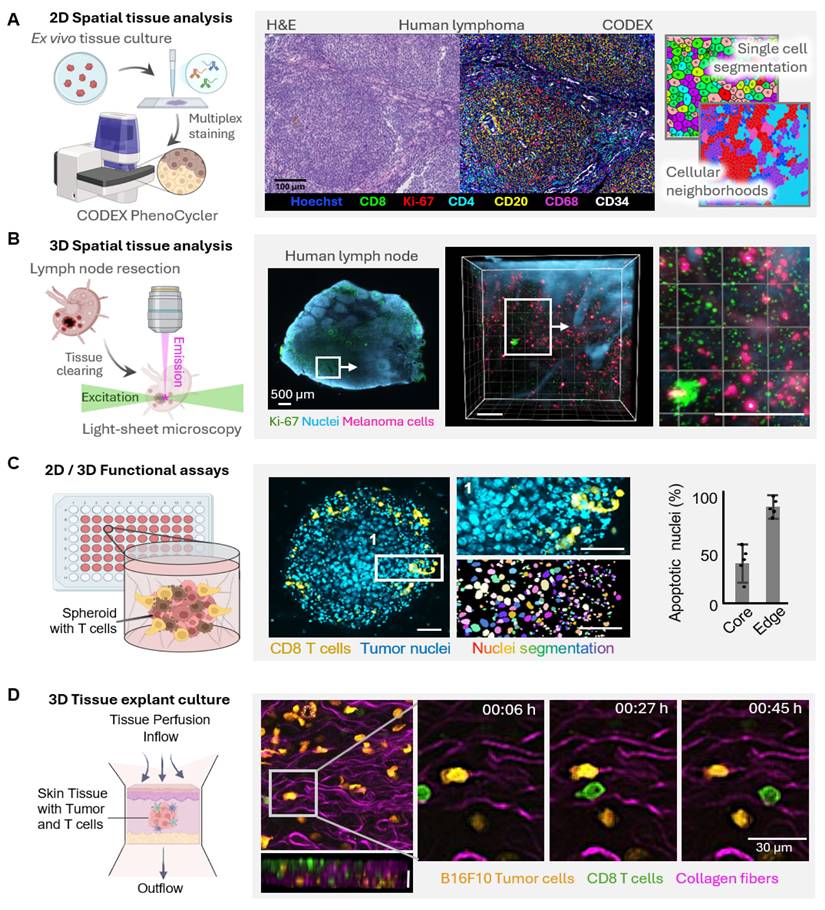

Given that cancer models transitioning from 2D monolayers to complex multicellular 3D systems and ex vivo tissues have developed, analytical methodologies must evolve in synchrony to accommodate their dynamic spatial and functional complexity (Figure 3). High-content microscopy and multiplex immunofluorescence currently provide high-dimensional mapping of immune cell phenotypes and spatial relationships in tumor models, elucidating infiltration patterns and cellular neighbourhoods (Figure 3A). In intact tissues, tissue clearing together with light-sheet microscopy enables the volumetric visualization of the tumor and immune architectures at cellular resolution (Figure 3B). Dynamic live-cell imaging of 3D spheroids allows time-resolved readouts of immune-tumor interactions showing, among other things, spatial gradients in cytotoxic efficacy between spheroid peripheries and hypoxic cores (Figure 3C). Multiphoton imaging of ex vivo tissue explants, in addition, allows for the preservation of native TMEs, provides access to the migration, infiltration, and tumor-immune contact dynamics in real time, complementary to the TMEs methods described (Figure 3D). Taken together, these emergent imaging techniques enable a holistic, spatiotemporal, and functional outlook of cancer models, linking molecular mechanisms to therapeutic effectiveness, and advance their status as quantitative theranostic platforms at the crossroads of experimental oncology and clinical translation.

These spatially resolved readouts provide dual value in theranostics by functioning as diagnostic tools, identifying predictive tissue signatures of response, and as mechanistic assays that guide therapeutic optimization. For instance, correlating PD-L1 expression patterns with T cell localization in treated tumor slices can clarify why certain regions resist immune attack. Integrating these spatial data with transcriptomic or metabolomic profiles enables multiscale models of treatment efficacy. Ultimately, applying these technologies to patient-derived explants transforms them into quantitative theranostic platforms, thereby linking drug exposure, biological mechanism, and clinical outcome in one experimental system.

From modeling to decision-making

Across a spectrum of cancer models from rapid 2D assays to complex in vivo xenografts, each platform addresses a different stage of the translational continuum. Simple models offer speed and scalability for early drug triage, whereas complex 3D systems deliver patient-specific biology at high spatial and temporal resolution. Such a blend of strategies in the context of FPM provides both throughput and physiological relevance. For theranostic purposes, the model itself becomes part of the diagnostic process and works as a living sensor reporting functional responses to therapy in real time. The selection of the best model is in turn subject to answering the clinical question: Is a rapid cytotoxicity screen needed for immediate therapy selection, or is an immune-competent tissue assay required to predict the efficacy of checkpoint blockade? This comprehensive perspective paves the way for the next generation of ex vivo culture platforms that aspire to combine clinical practicality with microenvironmental fidelity.

Evolving analytical strategies for spatial and functional characterization of complex tumor models. As cancer models advance from simple monolayers to complex multicellular systems, analytical tools must equally evolve to capture the increasing spatial and functional. (A) 2D spatial tissue analysis enables high-dimensional mapping of immune cell phenotypes within complex tumor models. Representative images illustrate immune infiltration patterns of immune cells in human lymphoma, with single-cell segmentation revealing phenotypic diversity and cellular neighborhoods. Scale bar, 100 µm. (B) Tissue clearing and light-sheet microscopy enables 3D spatial analysis and resolves the volumetric organization of tumor models and associated immune structures at cellular resolution. Shown is a resected and cleared human lymph node imaged by light-sheet microscopy, revealing infiltration with melanoma cells. Scale bars, 200 µm. (C) Dynamic functional assays based on live imaging of 3D tumor spheroids provide functional readouts in real-time. Here, a B16F10 melanoma spheroid is infiltrated by CD8⁺ T cells (green). Quantitative analysis of apoptotic nuclei (cyan) shows that killing efficacy is highest at the spheroid periphery, whereas tumor cells in the hypoxic core resist immune attack. Scale bars, 100 µm. (D) Ex vivo tissue explant cultures preserve the structural integrity and TME of intact tissue while enabling time-resolved observation of immune-tumor cell interactions. Multiphoton imaging of mouse skin explants containing melanoma cells (magenta) and CD8⁺ T cells (green) illustrates cytotoxic T cell infiltration and tumor-immune cell interactions and a z projection depicting a cross section of the tissue. Scale bar, 30 µm.

The ultimate vision reflects the theranostic principle by linking diagnostics directly to therapeutic decision-making. Utilizing patient-derived 3D models as personalized avatars, they are able to predict therapeutic benefit, explain resistance mechanisms, and identify companion biomarkers in this paradigm. As bioengineering, imaging, and computational analytics become increasingly intertwined, these living tumor systems will further cement the FPM role in creating a bridge between preclinical modelling and bedside decision-making.

Across different platforms, these models also serve important roles in the development and evaluation of diagnostic tools and theranostic agents. 2D cell cultures support high-throughput screening that can be used for early diagnostic triaging, and rapid cytotoxicity readouts such as LDH-release assays can quickly identify drug sensitivity profiles that guide early treatment decisions [36]. 3D spheroids and PDOs enable real-time imaging of drug distribution, retention, and treatment response, providing functional readouts that more closely approximate in vivo behavior [79]. Scaffold-based models can recapitulate specialized tissue structures such as skin, bone, or other organ-specific architectures, offering platforms for validating structure-dependent scenarios and localized theranostic delivery strategies [51]. Microfluidic systems further enable dynamic monitoring of drug perfusion, biomarker release, and cell-cell interactions under controlled flow conditions, making them valuable for testing pharmacokinetics-linked diagnostic markers and evaluating tracer transport [80]. Ex vivo tissue piece cultures and xenograft models preserve the native TME, allowing assessment of immune-tumor interactions, immune-cell infiltration, and TME-dependent imaging signatures [81]. Together, these complementary model systems create a translational continuum for optimizing diagnostic modalities and theranostic approaches, from rapid drug-sensitivity assessment to biologically faithful validation of imaging-based therapeutic monitoring.

To support practical decision-making in FPM, we provide a model-selection guiding flowchart that integrates clinical urgency, tissue availability, assay requirements, and model complexity (Figure 4). The workflow begins with the patient's clinical question, typically the need to identify an effective therapy within a defined treatment window, and links this directly to the type of tissue obtained (fresh vs. FFPE) and the amount available. For cases with very high treatment urgency (<1 week), rapid, low-cost 2D cultures, which can deliver fast cytotoxicity or flow cytometry-based readouts should be prioritized. For a window of 2-3 weeks, simple 3D systems like spheroids can be used, which maintain reasonable turnaround times and potentially improved readouts compared to 2D cultures. Low-urgency scenarios (>3 weeks) allow the use of more complex systems, such as organoids, scaffold-based models and microfluidic CoC platforms, in which live microscopy can be applied, e.g., to identify T-cell motility in response to immunotherapies. When larger tissue resections are available, ex vivo tissue pieces or xenografts can be performed, which provide the highest physiological relevance including intact TME architecture and tumor heterogeneity. At each step, the flowchart pairs available models with recommended readouts to assess tumor cell killing and antitumoral (immune) mechanisms, such as real-time microscopy, fluorescent assays, cytokine measurements, or tissue-level biomarkers. It also indicates cost and throughput to facilitate a balanced selection. By presenting these options side-by-side, the guide offers default choices for common clinical situations.

Integration, translation and innovation

As cancer modelling continues to evolve, the next step is not only the creation of ever more complex systems, but the integration of existing models into coherent translational pipelines. Rapid 2D and spheroid assays can serve as front-line functional screens, while organoids, perfused explants, and xenografts provide higher-fidelity validation. The incorporation of immune components and advanced imaging makes these models particularly relevant for personalized immunotherapy. Standardization and scalability remain essential for the routine clinical application of these tools. Protocols for tissue handling, culture conditions, and data interpretation must be harmonized across centers.

To support immunotherapy evaluation across diverse experimental systems, Table 2 provides a practical summary of how immune cells can be incorporated into common 2D, 3D, ex vivo, and in vivo tumor models. For each platform, we outline straightforward co-culture starting procedures, key time-course readouts, including infiltration, killing activity, and cytokine changes, and frequent technical challenges with troubleshooting solutions. Presenting these considerations side-by-side offers an accessible operational guide to help researchers select and implement the most suitable immune-competent model for functional precision immunotherapy studies.

Model-selection workflow for FPM. Flowchart guides tumor model selection by linking clinical urgency, tissue availability, readouts and costs to support FPM decisions. Multiomics analysis of FFPE tissues enable the characterization of the immune TME to guide immunotherapy selection as well as the identification of drug or antibody targets on tumor cells. While antitumoral killing assays of fresh tissue will be used for treatment sensitivity predictions. Treatment urgency (high, medium and low) determines culture models. Sufficient tissue quantity enables testing with ex vivo tissue pieces culture or xenografts. Each model is paired with its suitable readout technologies and costs. Left: general workflow; right: detailed workflow.

Clinical and Preclinical Use of Patient-Derived Cancer Models in FPM

| Cancer | Patient Samples | Study Type | Model & Approach | Major Significance | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML | 133/78/41 diagnosed/ relapsed/refractory | Prospective, clinical trial | 2D-Suspension, 515 drugs screened | Led to 59% response rate in R/R AML, including 45% complete remission | Malani et al. [36] |

| Hematologic Cancers | 143 patients, and 56 treated based on FPM | Prospective, clinical trial | 2D-Suspension, Single-cell FPM, 139 drugs screened | 54% of patients showed improved PFS, with 40% experiencing prolonged responses | Kornauth et al. [22] |

| AML | 28 patient samples, FPM study | Prospective, clinical trial | 2D-Suspension, 187 drugs screened | Induces clinical responses in progressive AML and predicts emerging drug resistance | Pemovska et al. [35] |

| Solid Tumors | 568 biopsies of various cancer types | Prospective, co-clinical trial | 2D-Monolayer, 6 TKIs tested | Quantify drug sensitivity and reflect clinical response | Kodack et al. [38] |

| Pediatric Cancers | 21 R/R patients, FPM study | Prospective, clinical trial | 2D cell cultures, 125 drugs screened | 5 cases out of 6 experienced an improvement in PFS, after FPM-guided treatments | Acanda et al. [10] |

| Lung Cancer | 20 biopsies of lung cancer | Prospective, co-clinical trial | 3D-Spheroids, 6 TKIs tested | Strong predictive performance in co-clinical trials, with an accuracy of 85% | Shie et al. [42] |

| Ovarian Cancer | 44 newly diagnosed eligible patients | Prospective, co-clinical trial | 3D-Spheroids, 6 chemotherapy drugs | High overall prediction of clinical response accuracy of 89% | Shufordet al. [43] |

| mGI cancers | 29 biopsy samples from 21 patients | Prospective, co-clinical trial | 3D-Organoids, 55 drugs screened | High predictive accuracy, 100% sensitivity and 93% specificity | Vlachogiannis et al. [48] |

| Breast cancer | 35 patients | Prospective, co-clinical trial | 3D-Organoids, 49 drugs screened | Predicting clinical response with 82.35% sensitivity and 69.23% specificity | Chen et al. [49] |

| Breast cancer | 2 patient samples | Pre-clinical study | Polymer Scaffold, 2 chemotherapy drugs | Discover heterogeneity in drug response | Nayak et al. [54] |

| Prostate cancer | 2 patient samples | Pre-clinical study | 3D-Hydrogels, Docetaxel treated | Demonstrated potential for drug screening | Fong et al. [55] |

| CRC | 23 patient samples | Pre-clinical study | Tissue scaffolds, 5-FU and FOLFIRI | Serve as a patient-specific platform for drug testing | Sensi et al. [56] |

| Breast cancer | 2 patient samples | Pre-clinical study | Cancer-on-a-chip, CAR T cell therapy | Enables personalized CAR-T efficacy and safety evaluation | Maulana et al. [60] |

| Lung Cancer | 12 patient samples | Pre-clinical study | Cancer-on-a-chip, Anti-PD-1 therapy | Enables assessment of patient-specific anti-PD-1 response | Veith et al. [61] |

| GBM | 7 grade IV samples | Pre-clinical study | Tumor fragments, 2 Immunotherapies | Enables multidimensional personalized assessment of immunotherapy response | Shekarian et al. [62] |

| PDAC | 3 patient samples | Pre-clinical study | Tumor Slices Chemotherapy | Enables chemotherapy testing and personalized therapy assessment | Hughes et al. [65] |

| Gallbladder cancer | 12 patients treated based on FPM | Prospective, clinical trial | Xenografts, 5 chemotherapy drugs | PDX-guided chemotherapy significantly upregulated OS and DFS of patients | Zhan et al. [72] |

| HNSCC | 49 patient samples, PDX clinical trial | Pre-clinical study | Xenografts, Cetuximab tested | Serve as a patient-specific platform for testing drug sensitivity | Yao et al. [73] |

Abbreviations: AML, Acute Myeloid Leukemia; R/R, Relapsed/Refractory; PFS, Progression-Free Survival; TKIs, Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors; mGI cancer, metastatic gastrointestinal cancer; CRC, Colorectal Cancer; GBM, Glioblastoma Multiforme; PDAC, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma; OS, Overall Survival; DFS, Disease-Free Survival; HNSCC, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

Immune co-culture workflow, readouts, and troubleshooting across cancer models

| Model | Basic Co-culture Setup | Key Readouts | Common Issues | Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Cell Culture | Tumor cells in plate and add activated T cells (Chakraborty et al. [89]) | Killing assays such as LDH release and flow cytometry, cytokine assay by ELISA | Over-rapid cancer cell killing, non-physiological interactions, not ideal for immunotherapy test | Lower E:T ratio, reduce activation strength or only for non-immunotherapies |

| 3D Spheroids | Form spheroids with ultra-low attachment plates or hydrogel matrix and co-incubate immune cells (Lo et al. [90]) | Live-cell imaging of infiltration, confocal microscopy, apoptosis markers, viability dyes | Limited immune infiltration, spheroid size variability | Standardize spheroid size, optimize matrix stiffness |

| Organoids (PDOs) | Grow tumor cells and peripheral T cells or NK cells in Matrigel domes (Sun et al. [91]) | Imaging-based killing assays, cytokines, single-cell profiling, flow cytometry after dissociation | Dense Matrigel barrier, contamination by fibroblasts, slow establishment | Use diluted ECM, mechanical dissociation for uniformity, pre-expand TILs |

| Scaffold-based Models | Seed tumor cells in scaffolds and add immune cells (Mistretta et al. [92]) | Infiltration depth, matrix remodeling, live imaging, killing assays | Immune cells trapped at scaffold surface; irregular perfusion | Adjust pore size, reduce hydrogel density, use dynamic flow |

| Microfluidic CoC | Load tumor cells and other TME components into microfluidic channels (Ao et al. [93]) | High-resolution monitoring of infiltration dynamics, killing, cytokine gradients | Channel clogging; shear-stress-induced immune dysfunction | Reduce cell density, optimize flow rate, pre-coat channels with ECM |

| Tissue Pieces (Ex vivo Slices) | Culture 250 µm tumor slices (Jiang et al. [94]) or tissue pieces (Zhang et al. [66]) to maintain TME for immunotherapy assays | Multiphoton imaging (motility, contacts), histology, multiplex microscopy, cytokine secretion | Rapid tissue decay; poor penetration of immune cells | Use oxygenated media, maintain <48h, cut thinner slices, embed in agarose |

| Xenografts / PDX | Engraft tumor (immunodeficient mice for adoptive transfer of T cells, Stenger et al. [95]) or humanized mice (Meraz et al. [96]) | In vivo immune cell infiltration (histology, flow cytometry), tumor size, serum cytokines | Human T-cell exhaustion; variability between animals | Use fresh T cells, optimize dosing schedule, include ≥5-6 mice per group |

ECM, extracellular matrix; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; E:T, effector:target; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NK cells, natural killer cells; TILs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; TME, tumor microenvironment; PDOs, patient-derived organoids; PDX; patient-derived xenografts

In efforts to enhance reproducibility, we outline recommendations for feasible actions to decrease batch-to-batch variation across tumor model systems. For 2D cultures, ensuring strictly controlled seeding density and the use of aliquoted master stocks significantly enhances consistency [82]. When producing spheroids, plate format, cell aggregation time, and initial cell counts should be standardized to minimize this variability by batch [83]. Organoid variability may be reduced by establishing well-defined protocols for tumor tissue dissociation, ECM embedding, serial passaging, and morphological assessment, as well as applying strict quality control programs [84]. The variability of scaffold and microfluidic models can be minimized by using commercially standardized fabrication parameters and calibrating flow rates before each experiment [85]. For tissue slices, consistency improves when cuts are made using automated vibratomes at fixed thickness and when sampling is taken from equivalent tumor regions. While xenografts inherently demonstrate a greater biological variability, standardized implantation site, fragment size, or cell number and treatment schedules can increase the robustness of these assays [86]. Incorporating these strategies enhances the reproducibility of studies and enables more accurate model selection.

In addition to traditional small molecule- and antibody approaches, new molecular platforms such as supramolecular systems and DNA-based nanotechnology have begun to gain significance in cancer theranostics. Supramolecular systems are organized structures formed through reversible, non-covalent molecular interactions, and can form dynamic assemblies with advantages including low immunotoxicity, target delivery and controlled release, making them well suited for precision medicine applications [87]. Another example is DNA nanostructures, such as DNA origami, enable programmable spatial organization of therapeutic and diagnostic components, supporting precise delivery, targeting and imaging [88]. When evaluated in FPM models, these platforms provide powerful tools for the systematic assessment of patient-specific uptake, efficacy, and toxicity, while the integration of advanced culture models with these technologies represents a promising direction for future innovation.

Ethical and governance considerations

The use of patient-derived material in FPM also raises important ethical and governance issues. In most settings, participation requires written informed consent that specifies how fresh tissue will be used for ex vivo testing, what level of clinical interpretation can be expected, and under what conditions data may be shared. All assay-derived data should be stored on secure, access-controlled institutional servers and handled in accordance with local data protection regulations [97,98]. Functional readout interpretation is typically carried out by a multidisciplinary tumor board or equivalent oversight group to ascertain that experimental findings are contextualized against known clinical, pathological, and genomic information. Due to the uncertainty intrinsic in functional assays, results should be communicated to clinicians and patients in unambiguous, standardized language, and avoid overstating predictive value [99]. The implementation of these ethical and governance checks is a prerequisite to the responsible and clinically meaningful application of FPM approaches.

Summary

FPM has shown substantial clinical utility, and the rapid advancement of culture technologies has greatly expanded its application potential. However, translation of complex cancer models into widespread FPM clinical practice is not without its challenges. Importantly, complexity of a model should not be sought simply for its own sake. Although advanced models like scaffold-based cancer models, tumor explants and PDXs present better representations of the biology of tumors, the complexity and cost in this approach render them less generally applicable to the clinic but still powerful tools in preclinical research. Simpler methods such as 2D suspension cultures, however, remain essential, particularly for the FPM application of hematological malignancies, for their cost-effectiveness and time value with predictive potential in clinical practice. In the case of solid tumors and immunotherapy, however, maintenance of the stromal and immune elements is key, as therapeutic success is often contingent upon the preservation of TME interactions. In this regard, 3D spheroids and organoids are the currently most established systems for performing FPM studies, and in vivo validation by PDXs complementarily supports this development. Recent advancements such as hybrid 3D constructs, and perfused tissue explant or bioreactor systems, continue this momentum by sustaining complex human tissues ex vivo for functional evaluation and mechanistic investigation.

In summary, FPM is advancing rapidly, and the growing array of cancer models brings many new possibilities while posing ongoing challenges for standardization and clinical integration. The next step will be harmonized standards for model selection and analytical readouts, ensuring that these innovations can be integrated into routine precision oncology and theranostic practice.

Future outlook

As new anticancer agents continue to be added to the treatment pipeline, it is becoming ever more critical to determine which treatment is the best for each patient. Analogous to the development of antibiotic medications, antibiotics such as penicillin and other agents have existed and remain evidence-based treatment options; however, the increasing presence of a spectrum of antibiotics as well as antibiotic resistance has accelerated the implementation of antimicrobial susceptibility testing, leading to more targeted activity against susceptible agents [100]. All indications now, excluding surgery, for treatment of cancer generally follow the same standard protocols followed for the treatment of the malignancy and there is typically a progression of cancer with first-line, second- and third-line drugs in the event that other cancer therapies fail. Although this progressive approach has historically helped the vast majority of patients, this stepwise pathway has led to some patients missing out on receiving suitable pharmacotherapies [101]. FPM, which offers a rapid and direct method of matching drugs to patient-specific responses, holds great promise for transforming this paradigm and personalizing cancer treatment more effectively in the future. When integrated with imaging and spatially resolved analyses, FPM could evolve into a fully theranostic approach by linking predictive diagnostics directly to therapeutic decision making.

FPM has demonstrated great adaptability and strong benefits in hematologic malignancies owing to the relative ease of sampling and model development. Its remarkable improvement of treatment accuracy and effectiveness is already documented in several prospective studies and can help initiate a wider range for therapeutic incorporation [22,36]. The question is how to maximize this success into immunotherapy of solid tumors where TME complexity and analytical depth are required.

Moving forward, it will be essential to establish standardized protocols and readouts, which are critical for integrating FPM into routine clinical practice across cancer types. Applying FPM to solid tumors remains particularly challenging. Very few prospective studies have been conducted, and researchers must identify suitable models for different tumor types that are both practical and cost-effective [102]. Nonetheless, growing evidence from preclinical and co-clinical studies suggests that FPM in solid tumors is steadily advancing toward clinical translation. Future efforts should integrate immune-competent 3D and ex vivo tissue platforms with quantitative spatial and functional readouts, ensuring that the next generation of FPM assays not only predict response but also explain it, thereby realizing the vision of cancer theranostics.

Abbreviations

2D: two-dimensional; 3D: three-dimensional; TME: tumor microenvironment; ECM: extracellular matrix; PDX: patient-derived xenografts; FPM: Functional Precision Medicine; PDOs: patient-derived organoids; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; AI: artificial intelligence; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; LLPS: liquid-liquid phase separation; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; FOLFIRI: folinic acid, fluorouracil, and irinotecan; CoC: Cancer-on-a-Chip.

Acknowledgements

We thank Isabelle Rottmann (Werner Siemens Imaging Center, University of Tübingen) for providing light-sheet images of antibody-stained and cleared human lymph nodes. C.M.S. was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, University of Tübingen; the Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Tübingen; the State of Baden-Württemberg within the Centers for Personalized Medicine Baden-Württemberg (ZPM); the Mach-Gaensslen-Stiftung Schweiz; the Dres. Bayer-Foundation; Swiss Cancer Research (KFS-5114-08-2020); the European Union (ERC, 101116768); the German Research Foundation (EXC 2180 - 390900677; INST 37/1228-1 FUGG; INST 37/1302-1 FUGG; INST 37/1310-1 FUGG); the Brigitte und Dr. Konstanze Wegener-Stiftung; the Werner Jackstädt-Stiftung; and the Leukemia Research Foundation (1077776). B.W. was supported by the Adolf Leuze Stiftung and the German Research Foundation (DFG) (SFB TRR156, project number 555063886-WE6800/4-1 and 556020868-WE6800/5-1). C.M.S. and B.W. were supported by the Cluster of Excellence iFIT (EXC 2180) 'Image-Guided and Functionally Instructed Tumor Therapies', University of Tübingen and by the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung, BfR) under grant number 60-0102-01.P641-12572660. Y.Z. was supported by the China Scholarship Council (202107040026). N.P. was supported by the Promotionskolleg, Faculty of Medicine, University of Tübingen. We acknowledge support from the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Tübingen.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Y.Z., C.M.S.

Writing - Original Draft: Y.Z.

Writing - Review & Editing: All authors

Visualization: Y.Z., N.P., B.W.

Supervision: B.W., C.M.S.

Project Administration: Y.Z., C.M.S.

Funding Acquisition: B.W., C.M.S.

Competing Interests

C.M.S. is a cofounder and shareholder of Vicinity Bio GmbH, and is a scientific advisor to and has received research funding from Enable Medicine Inc. C.M.S. and B.W. are listed inventors on European patent application No. EP4563690A1 describing a bioreactor system for multiphoton microscopy of ex vivo tissue explants. Y.Z. and N.P. declare no competing interests related to this work.

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-63

2. Wells JM. Cancer burden, finance, and health-care systems. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:13-4

3. Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT. et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891-906

4. Baker BM, Chen CS. Deconstructing the third dimension - how 3D culture microenvironments alter cellular cues. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:3015-24

5. Tchafa AM, Ta M, Reginato MJ, Shieh AC. EMT Transition Alters Interstitial Fluid Flow-Induced Signaling in ERBB2-Positive Breast Cancer Cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;13:755-64

6. Yadav C, Evtushenko AS, Popov AB, Torres BL, Ahmed I, Dvinskikh L. et al. A 3D spheroid model for assessing nanocarrier-based drug delivery to solid tumors. NPJ Biomed Innov. 2025;2:37

7. Wang X. Highlights the recent important findings in cancer heterogeneity. Holist Integr Oncol. 2023;2:15

8. Gutmann DH, Boehm JS, Karlsson EK, Padron E, Seshadri M, Wallis D. et al. Precision preclinical modeling to advance cancer treatment. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2024 djae249

9. Letai A. Functional precision cancer medicine—moving beyond pure genomics. Nat Med. 2017;23:1028-35

10. Acanda De La Rocha AM, Berlow NE, Fader M, Coats ER, Saghira C, Espinal PS. et al. Feasibility of functional precision medicine for guiding treatment of relapsed or refractory pediatric cancers. Nat Med. 2024;30:990-1000

11. Scherer WF, Syverton JT, Gey GO. Studies on the propagation in vitro of poliomyelitis viruses. IV. Viral multiplication in a stable strain of human malignant epithelial cells (strain HeLa) derived from an epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix. J Exp Med. 1953;97:695-710

12. Kapałczyńska M, Kolenda T, Przybyła W, Zajączkowska M, Teresiak A, Filas V. et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures - a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Arch Med Sci AMS. 2018;14:910-9

13. Jubelin C, Muñoz-Garcia J, Griscom L, Cochonneau D, Ollivier E, Heymann M-F. et al. Three-dimensional in vitro culture models in oncology research. Cell Biosci. 2022;12:155

14. Liu Y, Wu W, Cai C, Zhang H, Shen H, Han Y. Patient-derived xenograft models in cancer therapy: technologies and applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:1-24

15. Bhimani J, Ball K, Stebbing J. Patient-derived xenograft models—the future of personalised cancer treatment. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:601-2

16. Wen S, Lin X, Luo W, Pan Y, Liao F, Wang Z. et al. Metabolic difference between patient-derived xenograft model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and corresponding primary tumor. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:485

17. Duan X-P, Qin B-D, Jiao X-D, Liu K, Wang Z, Zang Y-S. New clinical trial design in precision medicine: discovery, development and direction. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:1-29

18. Zareian S, Sardari S. From Molecules to Medicine: Navigating the Challenges of Network Science in Precision Medicine. J Mol Clin Med. 2024;7:2

19. Flobak Å, Skånland SS, Hovig E, Taskén K, Russnes HG. Functional precision cancer medicine: drug sensitivity screening enabled by cell culture models. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2022;43:973-85

20. Salmon SE, Hamburger AW, Soehnlen B, Durie BG, Alberts DS, Moon TE. Quantitation of differential sensitivity of human-tumor stem cells to anticancer drugs. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1321-7

21. Shoemaker RH, Wolpert-DeFilippes MK, Kern DH, Lieber MM, Makuch RW, Melnick NR. et al. Application of a human tumor colony-forming assay to new drug screening. Cancer Res. 1985;45:2145-53

22. Kornauth C, Pemovska T, Vladimer GI, Bayer G, Bergmann M, Eder S. et al. Functional Precision Medicine Provides Clinical Benefit in Advanced Aggressive Hematologic Cancers and Identifies Exceptional Responders. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:372-87

23. Turpin R, Peltonen K, Rannikko JH, Liu R, Kumari AN, Nicorici D. et al. Patient-derived tumor explant models of tumor immune microenvironment reveal distinct and reproducible immunotherapy responses. Oncoimmunology. 14: 2466305.

24. Magré L, Verstegen MMA, Buschow S, van der Laan LJW, Peppelenbosch M, Desai J. Emerging organoid-immune co-culture models for cancer research: from oncoimmunology to personalized immunotherapies. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e006290

25. Friedman AA, Letai A, Fisher DE, Flaherty KT. Precision medicine for cancer with next-generation functional diagnostics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:747-56

26. Kropivsek K, Kachel P, Goetze S, Wegmann R, Severin Y, Hale BD. et al. P856: A SINGLE-CELL FUNCTIONAL PRECISION MEDICINE LANDSCAPE OF MULTIPLE MYELOMA. HemaSphere. 2022;6:749-50

27. Potter DS, Du R, Bhola P, Bueno R, Letai A. Dynamic BH3 profiling identifies active BH3 mimetic combinations in non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:741

28. Dinić J, Jovanović Stojanov S, Dragoj M, Grozdanić M, Podolski-Renić A, Pešić M. Cancer Patient-Derived Cell-Based Models: Applications and Challenges in Functional Precision Medicine. Life. 2024;14:1142

29. Drexler HG. Establishment and culture of leukemia-lymphoma cell lines. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;731:181-200

30. Dellamonica D, Ruau D, Griffiths B, Rossi G, Li BT, Razavi P. et al. The AI revolution: how multimodal intelligence will reshape the oncology ecosystem. Npj Artif Intell. 2025;1:40

31. Hsu C-Y, Askar S, Alshkarchy SS, Nayak PP, Attabi KAL, Khan MA. et al. AI-driven multi-omics integration in precision oncology: bridging the data deluge to clinical decisions. Clin Exp Med. 2025;26:29

32. Van Zundert I, Fortuni B, Rocha S. From 2D to 3D Cancer Cell Models—The Enigmas of Drug Delivery Research. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:2236

33. Fu Y, Khoo BL, Lim CT. Advancements and challenges in culturing patient-derived cancer cells for personalized therapeutics. Front Lab Chip Technol. 2025;4:1663420

34. Dietrich S, Oleś M, Lu J, Sellner L, Anders S, Velten B. et al. Drug-perturbation-based stratification of blood cancer. J Clin Invest. 128: 427-45.

35. Pemovska T, Kontro M, Yadav B, Edgren H, Eldfors S, Szwajda A. et al. Individualized Systems Medicine Strategy to Tailor Treatments for Patients with Chemorefractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1416-29

36. Malani D, Kumar A, Brück O, Kontro M, Yadav B, Hellesøy M. et al. Implementing a Functional Precision Medicine Tumor Board for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2022;12:388-401

37. Rosenquist R, Bernard E, Erkers T, Scott DW, Itzykson R, Rousselot P. et al. Novel precision medicine approaches and treatment strategies in hematological malignancies. J Intern Med. 2023;294:413-36

38. Kodack DP, Farago AF, Dastur A, Held MA, Dardaei L, Friboulet L. et al. Primary Patient-Derived Cancer Cells and Their Potential for Personalized Cancer Patient Care. Cell Rep. 2017;21:3298-309

39. Costa EC, Moreira AF, de Melo-Diogo D, Gaspar VM, Carvalho MP, Correia IJ. 3D tumor spheroids: an overview on the tools and techniques used for their analysis. Biotechnol Adv. 2016;34:1427-41

40. Rodrigues T, Kundu B, Silva-Correia J, Kundu SC, Oliveira JM, Reis RL. et al. Emerging tumor spheroids technologies for 3D in vitro cancer modeling. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;184:201-11

41. Xu Z, Wang W, Cao Y, Xue B. Liquid-liquid phase separation: Fundamental physical principles, biological implications, and applications in supramolecular materials engineering. Supramol Mater. 2023;2:100049

42. Shie M-Y, Fang H-Y, Kan K-W, Ho C-C, Tu C-Y, Lee P-C. et al. Highly Mimetic Ex Vivo Lung-Cancer Spheroid-Based Physiological Model for Clinical Precision Therapeutics. Adv Sci. 2023;10:2206603

43. Shuford S, Wilhelm C, Rayner M, Elrod A, Millard M, Mattingly C. et al. Prospective Validation of an Ex Vivo, Patient-Derived 3D Spheroid Model for Response Predictions in Newly Diagnosed Ovarian Cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9:11153

44. Zhao Z, Chen X, Dowbaj AM, Sljukic A, Bratlie K, Lin L. et al. Organoids. Nat Rev Methods Primer. 2022;2:94

45. Mei J, Liu X, Tian H-X, Chen Y, Cao Y, Zeng J. et al. Tumour organoids and assembloids: Patient-derived cancer avatars for immunotherapy. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e1656

46. Mann B, Artz N, Darawsheh R, Kram DE, Hingtgen S, Satterlee AB. Opportunities and challenges for patient-derived models of brain tumors in functional precision medicine. Npj Precis Oncol. 2025;9:47

47. Hwangbo H, Chae S, Kim W, Jo S, Kim GH. Tumor-on-a-chip models combined with mini-tissues or organoids for engineering tumor tissues. Theranostics. 2024;14:33-55

48. Vlachogiannis G, Hedayat S, Vatsiou A, Jamin Y, Fernández-Mateos J, Khan K. et al. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science. 2018;359:920-6

49. Chen P, Zhang X, Ding R, Yang L, Lyu X, Zeng J. et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Can Guide Personalized-Therapies for Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer. Adv Sci. 2021;8:2101176

50. Hippler M, Lemma ED, Bertels S, Blasco E, Barner-Kowollik C, Wegener M. et al. 3D Scaffolds to Study Basic Cell Biology. Adv Mater Deerfield Beach Fla. 2019;31:e1808110

51. Abuwatfa WH, Pitt WG, Husseini GA. Scaffold-based 3D cell culture models in cancer research. J Biomed Sci. 2024;31:7

52. Kim T-E, Kim CG, Kim JS, Jin S, Yoon S, Bae H-R. et al. Three-dimensional culture and interaction of cancer cells and dendritic cells in an electrospun nano-submicron hybrid fibrous scaffold. Int J Nanomedicine. 2016;11:823-35

53. Aguado BA, Hartfield RM, Bushnell GG, Decker JT, Azarin SM, Nanavati D. et al. Biomaterial Scaffolds as Pre-metastatic Niche Mimics Systemically Alter the Primary Tumor and Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7:e1700903

54. Nayak B, Balachander GM, Manjunath S, Rangarajan A, Chatterjee K. Tissue mimetic 3D scaffold for breast tumor-derived organoid culture toward personalized chemotherapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2019;180:334-43

55. Fong ELS, Martinez M, Yang J, Mikos AG, Navone NM, Harrington DA. et al. Hydrogel-Based 3D Model of Patient-Derived Prostate Xenograft Tumors Suitable for Drug Screening. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:2040-50

56. Sensi F, D'Angelo E, Piccoli M, Pavan P, Mastrotto F, Caliceti P. et al. Recellularized Colorectal Cancer Patient-Derived Scaffolds as In Vitro Pre-Clinical 3D Model for Drug Screening. Cancers. 2020;12:681

57. Cauli E, Polidoro MA, Marzorati S, Bernardi C, Rasponi M, Lleo A. Cancer-on-chip: a 3D model for the study of the tumor microenvironment. J Biol Eng. 2023;17:53

58. Jouybar M, de Winde CM, Wolf K, Friedl P, Mebius RE, den Toonder JMJ. Cancer-on-chip models for metastasis: importance of the tumor microenvironment. Trends Biotechnol. 2024;42:431-48

59. Mehta P, Rahman Z, ten Dijke P, Boukany PE. Microfluidics meets 3D cancer cell migration. Trends Cancer. 2022;8:683-97

60. Maulana TI, Teufel C, Cipriano M, Roosz J, Lazarevski L, van den Hil FE. et al. Breast cancer-on-chip for patient-specific efficacy and safety testing of CAR-T cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31:989-1002.e9

61. Veith I, Nurmik M, Mencattini A, Damei I, Lansche C, Brosseau S. et al. Assessing personalized responses to anti-PD-1 treatment using patient-derived lung tumor-on-chip. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5:101549

62. Shekarian T, Zinner CP, Bartoszek EM, Duchemin W, Wachnowicz AT, Hogan S. et al. Immunotherapy of glioblastoma explants induces interferon-γ responses and spatial immune cell rearrangements in tumor center, but not periphery. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabn9440

63. Powley IR, Patel M, Miles G, Pringle H, Howells L, Thomas A. et al. Patient-derived explants (PDEs) as a powerful preclinical platform for anti-cancer drug and biomarker discovery. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:735-44

64. Avena P, Zavaglia L, Casaburi I, Pezzi V. Perfusion Bioreactor Technology for Organoid and Tissue Culture: A Mini Review. Onco. 2025;5:17

65. Hughes D, Evans A, Go S, Eyres M, Pan L, Mukherjee S. et al. Development of human pancreatic cancer avatars as a model for dynamic immune landscape profiling and personalized therapy. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadm9071

66. Zhang Y, Foth I, Makky A, Bucher P, Grimm M, Bruch P-M. et al. Modeling Immunotherapies in Live 3D Human Cancer Tissue Bioreactors. Theranostics. 2026;16:3928-45

67. Hulen TM, Friese C, Kristensen NP, Granhøj JS, Borch TH, Peeters MJW. et al. Ex vivo modulation of intact tumor fragments with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 influences the expansion and specificity of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1180997

68. Okada S, Vaeteewoottacharn K, Kariya R. Application of Highly Immunocompromised Mice for the Establishment of Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) Models. Cells. 2019;8:889

69. Goto T. Patient-Derived Tumor Xenograft Models: Toward the Establishment of Precision Cancer Medicine. J Pers Med. 2020;10:64

70. Wang M, Yao L-C, Cheng M, Cai D, Martinek J, Pan C-X. et al. Humanized mice in studying efficacy and mechanisms of PD-1-targeted cancer immunotherapy. FASEB J. 2018;32:1537-49

71. Collins AT, Lang SH. A systematic review of the validity of patient derived xenograft (PDX) models: the implications for translational research and personalised medicine. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5981

72. Zhan M, Yang R, Wang H, He M, Chen W, Xu S. et al. Guided chemotherapy based on patient-derived mini-xenograft models improves survival of gallbladder carcinoma patients. Cancer Commun. 2018;38:48

73. Yao Y, Wang Y, Chen L, Tian Z, Yang G, Wang R. et al. Clinical utility of PDX cohorts to reveal biomarkers of intrinsic resistance and clonal architecture changes underlying acquired resistance to cetuximab in HNSCC. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:73

74. Bollhagen A, Bodenmiller B. Highly Multiplexed Tissue Imaging in Precision Oncology and Translational Cancer Research. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:2071-88

75. Ineveld RL van, Vliet EJ van, Wehrens EJ, Alieva M, Rios AC. 3D imaging for driving cancer discovery. EMBO J. 2022.

76. Pourmaleki M, Socci ND, Hollmann TJ, Mellinghoff IK. Moving Spatially Resolved Multiplexed Protein Profiling toward Clinical Oncology. Cancer Discov. 2023;13:824-8

77. Cao J, Li C, Cui Z, Deng S, Lei T, Liu W. et al. Spatial Transcriptomics: A Powerful Tool in Disease Understanding and Drug Discovery. Theranostics. 2024;14:2946-68

78. Way GP, Sailem H, Shave S, Kasprowicz R, Carragher NO. Evolution and impact of high content imaging. SLAS Discov. 2023;28:292-305

79. Chen L, Luo X, Zhang J, Zhang J, Yang C, Zhao Y. Harnessing Organoid Platforms for Nanoparticle Drug Development. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2025;19:6125-43

80. Li C, Holman JB, Shi Z, Qiu B, Ding W. On-chip modeling of tumor evolution: Advances, challenges and opportunities. Mater Today Bio. 2023;21:100724

81. Eguren-Santamaria I, Melero I, Rodríguez I, Ortego I, Armero M, Galvez-Cancino F. et al. Preclinical ex vivo and in vivo models to study immunotherapy agents and their combinations as predictive tools toward the clinic. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e011279

82. Kusena JWT, Shariatzadeh M, Studd AJ, James JR, Thomas RJ, Wilson SL. The importance of cell culture parameter standardization: an assessment of the robustness of the 2102Ep reference cell line. Bioengineered. 12: 341-57.

83. Saydé T, Hamoui OE, Alies B, Bégaud G, Bessette B, Lacomme S. et al. Reproducible 3D culture of multicellular tumor spheroids in supramolecular hydrogel from cancer stem cells sorted by sedimentation field-flow fractionation. J Chromatogr A. 2024;1736:465393

84. Sahin A, Sener-Akcora D, Yilmaz AM, Cakir MO, Karademir-Yilmaz B. Patient-Derived Cancer Organoids: Standardized Protocols for Tumor Cell Isolation, Organoid Generation, and Serial Passaging Across Multiple Cancers. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2025.

85. Piergiovanni M, B. Leite S, Corvi R, Whelan M. Standardisation needs for organ on chip devices. Lab Chip. 2021;21:2857-68

86. Evrard YA, Srivastava A, Randjelovic J, Doroshow JH, Dean DA, Morris JS. et al. Systematic Establishment of Robustness and Standards in Patient-Derived Xenograft Experiments and Analysis. Cancer Res. 2020;80:2286-97

87. Liu L, Huang F, Liu J, Xiao M. Recent advances of supramolecular systems in precise cancer theranostics. Supramol Mater. 2025;4:100116

88. Chen R, Jia X, Pang W, Yang Y, Zhou H, Gao Z. Applications of DNA origami in biomedicine: advances, challenges, and prospects. Adv Compos Hybrid Mater. 2025;8:375

89. Chakraborty S, Sridhar S, Ventura K, Sritharan R, Tocheva A, Sen T. Protocol to co-culture SCLC cells with human CD8+ T cells to measure tumor cell killing and T cell activation. STAR Protoc. 2025;6:103767

90. Lo HC, Choi H, Kolahi K, Rodriguez S, Gonzalez L, Chu F. et al. A 3D tumor spheroid model with robust T cell infiltration for evaluating immune cell engagers. iScience. 2025;28:112996

91. Sun H, Shi C, Fang G, Guo Q, Du Z, Chen G. et al. Functional tumor-reactive CD8 + T cells in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44:253

92. Mistretta KS, Coburn JM. Three-dimensional silk fibroin scaffolded co-culture of human neuroblastoma and innate immune cells. Exp Cell Res. 2024;443:114289

93. Ao Z, Cai H, Wu Z, Hu L, Li X, Kaurich C. et al. Evaluation of cancer immunotherapy using mini-tumor chips. Theranostics. 2022;12:3628-36

94. Jiang X, Seo YD, Chang JH, Coveler A, Nigjeh EN, Pan S. et al. Long-lived pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma slice cultures enable precise study of the immune microenvironment. OncoImmunology. 2017;6:e1333210

95. Stenger D, Stief TA, Kaeuferle T, Willier S, Rataj F, Schober K. et al. Endogenous T-cell receptor promotes in vivo persistence of CD19-CAR-T cells compared to a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated T-cell receptor knockout CAR. Blood. 2020;136:1407-18

96. Meraz IM, Majidi M, Meng F, Shao R, Ha MJ, Neri S. et al. An Improved Patient-Derived Xenograft Humanized Mouse Model for Evaluation of Lung Cancer Immune Responses. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1267-79

97. Stenzinger A, Moltzen EK, Winkler E, Molnar-Gabor F, Malek N, Costescu A. et al. Implementation of precision medicine in healthcare—A European perspective. J Intern Med. 2023;294:437-54