13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(7):3286-3320. doi:10.7150/thno.128348 This issue Cite

Review

Nanomedicine in Organ Transplantation: From Graft Preservation and Repair to Immunomodulation and Monitoring

1. Department of Radiology, Huaxi MR Research Center (HMRRC), Institution of Radiology and Medical Imaging, Liver Transplant Center, Organ Transplant Center, Department of General Surgery, Frontiers Science Center for Disease-Related Molecular Network, State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China.

2. Glasgow College, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 611731, China.

3. XiangYa School of Medicine, Central South University, Changsha 410013, China.

4. Psychoradiology Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, and Research Unit of Psychoradiology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China.

5. Laboratory of Liver Transplantation, Institute of Organ Transplantation, Key Laboratory of Transplant Engineering and Immunology, NHC, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China.

6. Xiamen Key Lab of Psychoradiology and Neuromodulation, Department of Radiology, West China Xiamen Hospital of Sichuan University, Xiamen 361021, China.

#These authors contributed equally: Leyi Wang and Chen Jin.

Received 2025-11-14; Accepted 2025-12-11; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

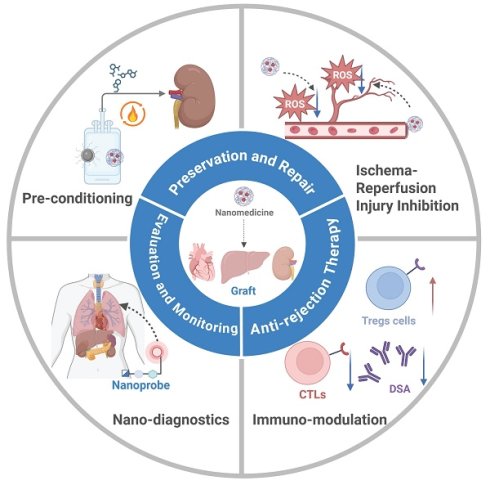

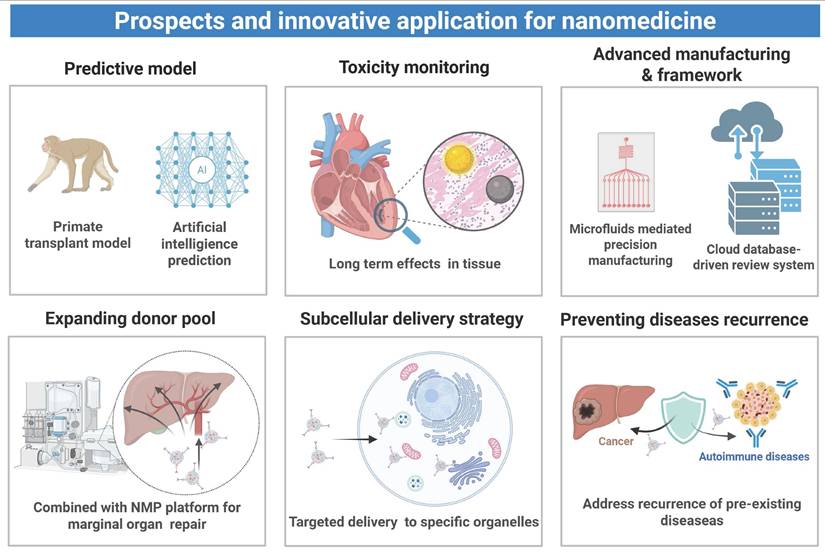

Organ transplantation remains a life-saving intervention for end-stage organ failure. However, its long-term success has been constrained by a few critical challenges, including few noninvasive diagnostic technologies for graft assessment, a lack of effective organ preservation and rewarming techniques to mitigate ischemic damage, the issue of ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), the risk of immune-mediated rejection and the requirement of advanced postoperative management. Nanomedicine has been explored for overcoming these challenges for organ transplantation. A myriad of polymeric, inorganic and hybrid nanocarriers have been employed for nanomedicine. Targeting and stimuli-responsive nanomedicine has been developed to improve drug distribution and enhance its therapeutic/diagnostic efficacy. Nanomedicine has been applied for rewarming of large-sized organs, IRI mitigation, immunomodulation, and real-time monitoring. This review examines the mechanisms, elaborates design principles, and covers the application of nanomedicine in organ transplantation at stages of pre- to post-transplantation. The challenges in clinical translation of nanomedicine are discussed and future research directions are proposed. This review will provide a consolidated framework for the development and application of nanomedicine for organ transplantation, ultimately improving the quality of life of transplant recipients.

Keywords: organ transplantation, nanomedicine, transplant rejection, ischemia-reperfusion injury

1. Introduction

Organ transplantation is a revolutionary treatment by itself that has significantly enhanced the lives and survival of a patient and continues to serve as an effective treatment to most of the terminal diseases [1]. Nonetheless, there are some challenges encountered in this area. The most urgent is the lack of organs donors in the world, as it make many patients live with life threatening complication in expectation of transplantation [2]. The risks of posttransplant rejection and complications are high including acute and chronic rejection, graft dysfunction, infection, and cancer all of which could not allow long-term survival of patients [3]. There were also some few organs (e.g., the lung, heart, liver, and kidney) clinically transplanted, and also the individual organs pose their own immunological problems. Liver is more immunologically tolerant compared to other ones [4], but transplantation in lungs, and islet cells usually produces intense immune response and auto immunity, and stronger immunosuppressive treatment is needed to tolerate the transplantation [5]. In addition to this, another unavoidable complication of transplantation is ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI). Its pathology also involves hypoxic injury during ischemia and oxidative stress and inflammation that occurs during reperfusion that results in the development of graft dysfunction, delayed recovery, and transplant failure [6]. Also, technical barriers exist in the monitoring of the postoperative abode things are very few effective noninvasive ways of detecting the delayed graft function at an early stage and in managing the complications caused by IRI or immunosuppression [7]. Novel approaches, including xenotransplantation, 3D bioprinting, nanoscale targeted delivery and diagnostics and mechanical perfusion, have been established to address the lack of organs, provide resistance against rejection, better graft preservation, and finally improve the graft function and long-term survival.

Nanomedicine is one of such strategies that has been extensively pursued in organ transplantation because of its size, which can be adjusted, surface properties customization, and targeting capability. It has carried out protective, regulatory and monitoring functions in the significant transplantation stages. Nanoparticles may be administered to eliminate and manage IRI by providing armed categories of active agents to curtail the circulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and to control oxidative tension, effectively decreasing tissue pathophysiology [8]. To resolve the problem of rejection, nanomedicine is capable of providing immunosuppressive agent at the site of grafting. This is the local method that would reduce side effects that may occur throughout the entire system, changes antigen-presenting cells to suppress immune response and fosters tolerance reducing the risk of rejection [9]. Moreover, cellular and molecular alterations of the transplanted organ can be accurately followed with the help of nanotechnology-based image techniques. Such methods provide noninvasive postoperative diagnosis, which is effective and assists it to detect the graft dysfunction in its initial stages [10]. Nanomedicine has therefore become a prospective transplantation medicine to aid in addressing the current clinical complications and enhance availability of organs and success of transplantation.

In this review, the mechanisms, designs, and applications of nanomedicine in organ transplantation are fully discussed. The main problems of organ transplantation have been described: invasive nature of biopsy-based checking of the organs, the inevitability of the effects of IRI at preservation, technical challenges of vitrification, and side effects of the existing immunosuppressants in dealings with the rejection. To solve these issues, benefits and designing concepts of nanomedicine are expounded. The strategy of nanocarriers to nanomedicine is classified and its targeting and ability to respond to stimuli are addressed. The use of nanomedicine in organ transplantation in recent applications is explained. Lastly, challenges of nanomedicine during translation into clinical practice are discussed and recommendations given on future directions. This review will offer a unified guide of application of nanomedicine in organ transplantation to enhance the living standards of transplant patients.

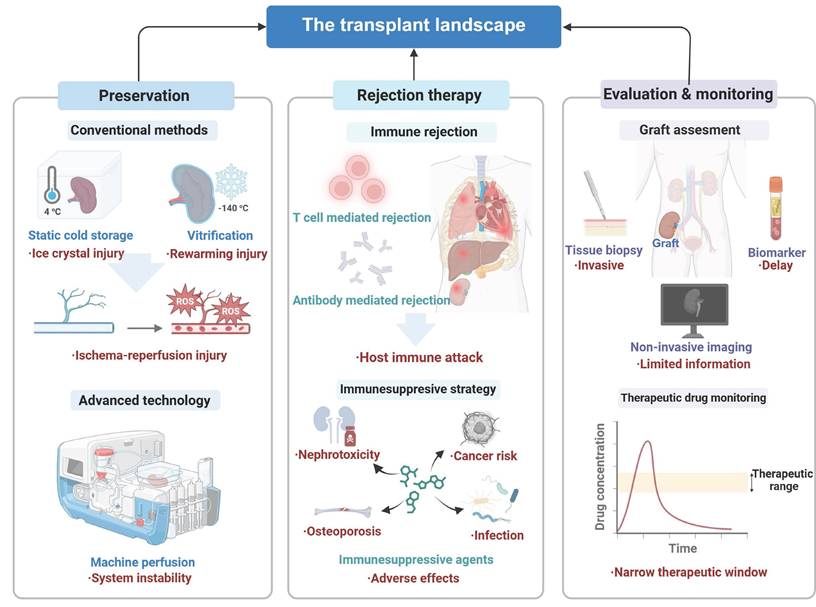

2. Current status and challenges in organ transplantation

The long-term survival rate and the quality of life of patients after organ transplantation are modulated by a multitude of factors, encompassing current diagnostic technologies, the quality of preserved organs, rewarming techniques, IRI, and postoperative management of rejection. Currently, principal impediments for successful organ transplantation include invasive biopsy-based methods for organ evaluation, cold IRI during preservation, bottlenecks in cryopreservation and rewarming technologies, and the complexity of postoperative immune rejection in conjunction with very few immunosuppressive therapeutic options (Figure 1).

2.1 Organ preservation and IRI

Organ preservation is a critical stage whereby the physiological process and structural integrity of the graft is maintained after it has been taken off the body of the donor. This is a preservation process which helps in transporting organs and preparing them to undergo transplantation surgery and perform pre-transplant evaluations of organ viability and execution of organ repair measures. The inherent drawbacks of the preservation methods and unavoidable damage of transplants are some of the current issues faced in the preservation process [11]. Preferably, organ preservation intervention would preserve the structural and functional integrity of the organ in an ex vivo state and enable the most protractable length of the transplantable period [12]. Normal processes like static cold storage (SCS) result in the development of ice crystals to destroy intracellular and extracellular materials [13]. In comparison, ultralow-temperature (-140 oC) vitrification, involving CPAs and propylene glycol, freezes organs much faster to avoid the formation of ice and reduce the effects of ice on tissues, and allows the storage of organs over a long period. Although this is an advantage, the method is hindered by low success in thawing organs [14]. Vitrified organs require rapid and constant warming to thaw successfully. Recrystallization is triggered by slow warming at between -40 °C and -60 °C, and the resulting ice crystals infiltrate and damage the cellular and mitochondrial membrane. The injury causes the discharge of damage-related molecular patterns (DAMPs) among other cellular content, which worsens oxidative stress and inflammation in case of severe IRI [15]. Moreover, extensive organs experience internal stress due to imbalanced thermal conductive effects during thawing and may lead to structural damage. Although convective techniques are fast and evenly distributed and have been successfully used to warm small samples very fast, they are not yet prepared to scale to organ scale [16].

Machine perfusion (MP) as an organ preservation method and dynamic lie on its lab-bench discovery finding to clinical practice. MP has also solved the limitations of the conventional immobile cold storage by replicating physiological conditions to provide continuous access to nutrients and oxygen to improve the quality of organs and broaden the donor population [17]. Two clinical modalities are commonly utilized, namely: NMP (normothermic machine perfusion) (35-38 °C) and hypothermic MP (0-12 °C). NMP is known to enhance metabolic activity and precise redox balance regulation is aware but hypothermic MP has the potential to compromise functional recovery by inhibiting metabolism [18]. MP helps in the use of marginal donor organs by increasing the preservation period. It has been shown to transport and evaluate organs, support early graft functional repair, and deliver drugs to specific areas of the body to reduce systemic side effects [19]. Nonetheless, MP has been faced with practical problems, whereby, the lengthening of the preservation time has been inadequate; functional recovery has been inadequate, and more organ loss has been witnessed as a result of system instability or perfusion failure [20].

Landscape of organ transplant management. The standard clinical management of organ transplants involves (1) preservation methods such as static cold storage, vitrification, and machine perfusion, (2) rejection therapy by addressing immune rejection with optimized immunosuppressive strategies, and (3) comprehensive evaluation including graft assessment and therapeutic drug monitoring. Created with BioRender.com.

An essential issue of MP to use as a mitigation strategy is IRI. The injury is started in the cold ischemia period and the duration of organ maintenance in a cold solution has a positive correlation with the amount of organ risks [21]. Transplantation normally goes hand in hand with IRI. Reproximal restoration of a hypoxic tissue causes a major generation of ROS, which induces cellular injury and inflammation, which causes IRI [22]. The impact of IRI varies significantly for different transplant types. In kidney transplantation, IRI causes acute tubular necrosis, delayed graft function, and reduced long-term survival [23]; in liver transplantation, it often results in graft dysfunction and post-surgical mortality, with a continued lack of effective interventions [24]; and in lung transplantation, it predominantly induces damage to an alveolar barrier and vascular endothelial cells [25]. Additionally, IRI also reduces the quality of donor organs of extended criteria donors (ECDs) as they are prone to damage by virtue of an advanced donor age, comorbidity, or unstable capillary functions of the body. The organs are frequently wasted following IRI, a fact that enhances the global organ shortage [26]. The existing clinical care of the IRI is not effective as a supportive care, and nanomedicine solutions have been researched in the context of amelioration of better targeting and regulated drug delivery.

Many donor organs are underused due to quality issues such as functional impairment or damage, as well as a higher risk of IRI. Tackling IRI during transplantation and repairing marginal organs could be innovative approaches to addressing these quality issues, and NMP perfusion emerges as a key platform for mitigating IRI through physiological maintenance and direct restorative effects [27]. For instance, NMP helps reduce fatty degeneration to remove excess lipids in steatotic livers which are common from marginal donations [28]. Moreover, grafts can be maintained in a perfusion system for several days before surgery, facilitating the clearance of potential infections [29].

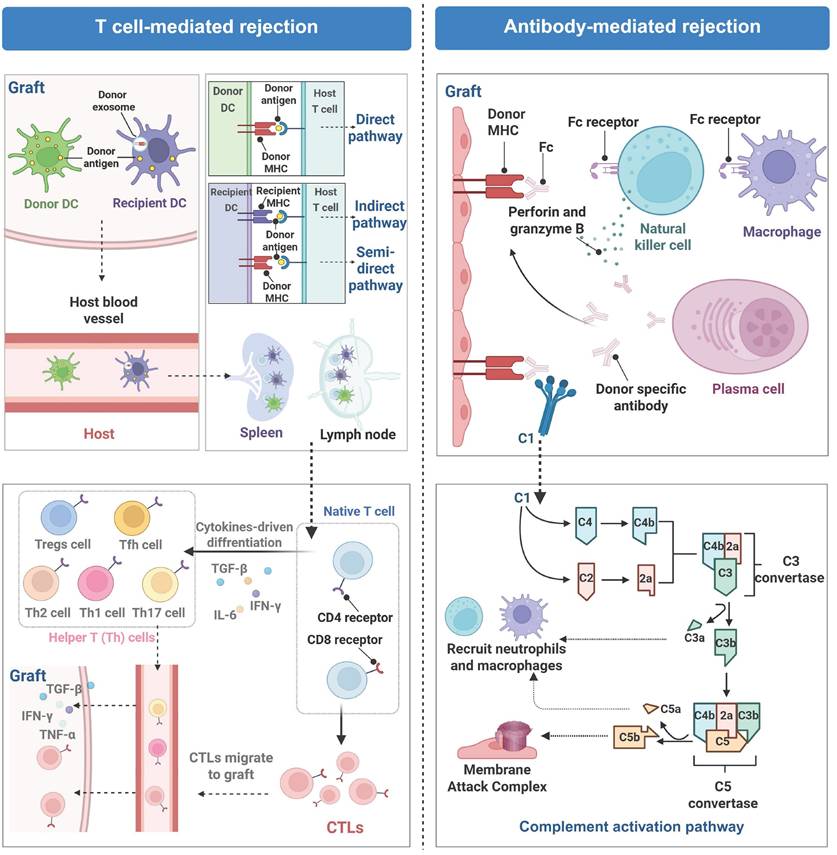

2.2 Posttransplant anti-rejection therapy

Rejection is a principal complication after organ transplantation and is characterized by an immune response triggered by the immune system of the recipient because the immune system treats the graft as a foreign or allogeneic tissue and initiates to eliminate it [30]. This response is fundamentally a defense mechanism of the host against allogeneic antigens while it results in structural damage to the graft and loss of its biological function [31]. On the basis of immune mechanisms and pathological characteristics, rejection is categorized into two primary types: T cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) and antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR). These two types may occur independently or coexist within the same graft (Figure 2).

TCMR is predominantly mediated by host effector T cells (including CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells), and they initiate rejection responses by recognizing mismatched signals from human leukocyte antigens (HLA) between a graft from a donor and its original organ in the recipient via their T-cell receptors (TCRs) [32]. Dendritic cells (DCs), professional APCs, present donor antigens through three pathways. The direct pathway involves recognition of foreign major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-antigen complexes on donor APCs by T cells; the indirect pathway involves recognition of donor antigens presented on their own MHC by T cells after processing by APCs. A recently discovered semidirect pathway involves acquisition of intact donor MHC-antigen complexes by recipient DCs through engulfing donor-derived extracellular vesicles (e.g., exosomes) and directly presenting them to naive T cells for antigen recognition [33]. Upon recognition of antigens presented by APCs and costimulatory molecules, T lymphocytes become activated, undergo differentiation, and clonally proliferate. The activation results in the secretion of inflammatory cytokines to facilitate local immune cell infiltration at the site of the graft, leading to tissue damage via cytotoxic mechanisms and inflammatory responses [34]. ABMR, which is characterized primarily by the presence of donor-specific antibodies (DSAs). DSAs specifically attack HLA class I or II molecules present on the surface of vascular endothelial cells of the graft and the attack is notably prevalent in cases of late-stage graft injury [35]. The endothelial damage is realized through complement activation and Fc receptor-mediated effector pathways, which subsequently trigger the recruitment of inflammatory cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, and B cells, to infiltrate the graft [36]. Acute ABMR typically manifests as tissue edema and vascular inflammation, whereas chronic ABMR results in intimal fibrosis [37].

In clinical practice, immune rejection is primarily managed through immunosuppression. The widely used drugs include tacrolimus (FK506) that blocks calcineurin; antimetabolites (e.g., rapamycin (RAPA) and everolimus) that curb immune cell growth; and glucocorticoids (e.g., methylprednisolone) that suppress inflammation and immune activity. Additionally, lymphocyte-depleting agents are used, including alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 antibody, and rituximab, a B-cell-targeting drug [38-42]. Although these treatments significantly improve short-term graft survival, long-term use of immunosuppressants carries severe risks, including a high rate of infection, cancer initiation, and chronic rejection [43]. Furthermore, these agents often have a narrow therapeutic window and display off-target toxicity, which prevent their application over an extended period.

Molecular mechanisms of T-cell-mediated rejection (TCMR) and antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR). TCMR involves migration of dendritic cells (DCs) to lymph nodes and spleens, where they activate T cells to initiate cellular immune responses against the graft. ABMR is primarily driven by donor-specific antibodies, leading to Fc receptor-mediated engagement and complement pathway activation, which collectively lead to graft endothelial injury. Created with BioRender.com.

2.3 Organ evaluation and outcome monitoring

The evaluation of the overall life cycle of handling organ transplantation such as organ functioning, timely disease identification, and examining the effectiveness of treatment also allow dynamically assessing the gland functioning ability and assist in timely clinical decision-making. Nonetheless, transplantation experiences significant diagnostic and follow-up problems. To avoid use of substandard grafts, tissue biopsy, which is the gold standard way of detecting abnormality in donor organs, may be invasive and is associated with sampling errors, complications, high cost, and damage of organs [44]. Moreover, noninvasive techniques that monitor tissue biopsy tend to fail to offer real-time but effective functional data of the donor organs, whether as a pre-transplant measure or even as a monitor to the organ recipient after transplantation. The tools that currently are noninvasive like the identification of blood or urine biomarkers are usually not specific or sensitive, which results in diagnosis delays [45, 46]. The state-of-the-art imaging procedures like MRI cannot see through molecule level graft operation, thus hampering accurate treatments in transplantation medicine [47].

The main challenges in the real-time monitoring are presented by two factors in the sphere of real-time monitoring: monitoring dynamic concentrations of drugs and their therapeutic effects, detecting the dynamics of pathological processes, and their progress. Indicatively, FK506 that has been largely used in clinical practice has a remarkably small therapeutic index. Even minor changes in drug levels in blood may lead to the development of serious side effects, such as nephrotoxicity, or insufficient immunosuppression, so, very specific monitoring of the drug concentration in blood is the key of immunosuppressive therapy [48]. Dynamic and complicated nature of IRI is what made the real-time monitoring of the pathological process hard. IRI plays an important role in dysfunction of posttransplant. There is a high speed of pathological processes, including localized reactive oxygen species (ROS) burst, mitochondrial dysfunction, and microenvironmental instability, hence, single-marker detection techniques cannot fully show the entire scope of damage [49]. The conventional biomarkers of serum like transaminases and tissue biopsies are mainly used to ascertain the end-stage of tissue damage. Currently, there are no successful ways of detecting early signs and tracing dynamic development of IRI. The difference in type and quality of organ donor also is an added complication to diagnosis [50]. Anxious oxidative injury patterns are revealed in different organs in IRI, and modern diagnostic tools are not able to recognize the differences between these patterns posing the threat of misdiagnosis. For instance, marginal donor organs, such as those from donors with fatty livers or elderly donors, are more vulnerable to IRI than organs from healthy donors. In the current diagnostic framework, these organ-specific physiological differences have not been comprehensively considered, and there is no standardized risk assessment to address the variation in the transplant [51]. Therefore, highly sensitive diagnostic tools are needed to real-time monitor dynamic processes of IRI across different organ types and donor qualities. The mechanisms of rejection include TCMR, as well as ABMR or a combination of both. As each type involves distinct immune activation pathways, accurate molecular-level diagnosis requires combining multiple specific biomarkers.

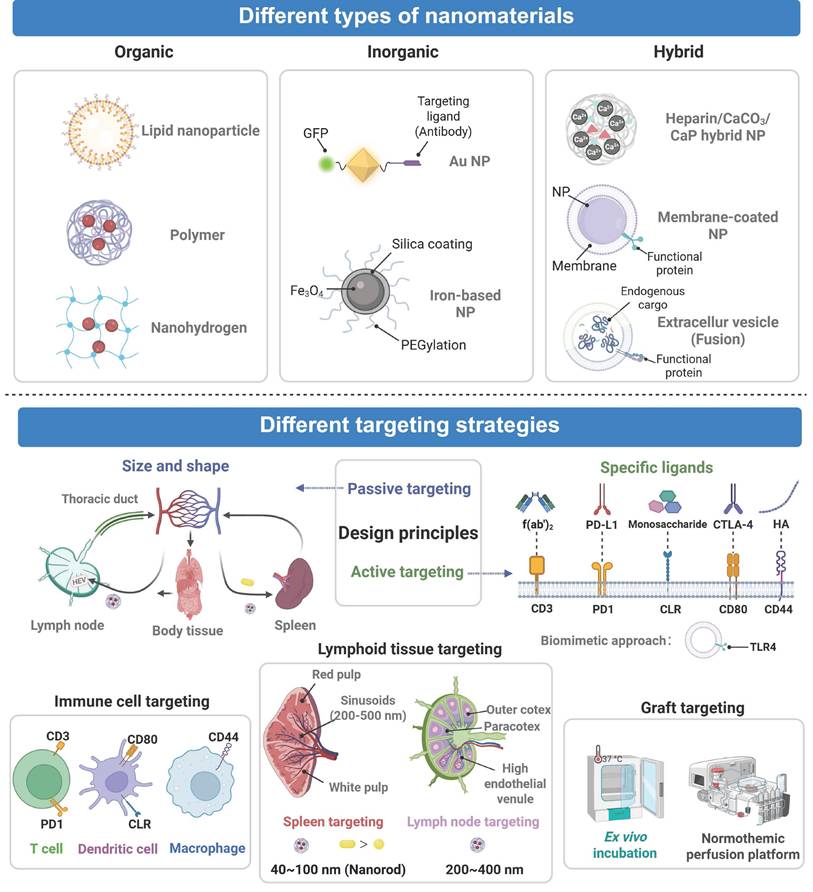

3. Design strategies and principles of nanomedicine in organ transplantation

Nanotechnology has been harnessed to address key challenges in organ transplantation. It improves diagnostic precision by enhancing target specificity and amplifying signals in a diseased area, and it allows the integration of high sensitivity, noninvasiveness, and multimodality in a single platform for earlier and more accurate real-time diagnosis. Meanwhile, nanomedicine has been used for organ preservation through magnetically induced uniform rewarming and targeted delivery of protective agents to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation caused by IRI. These nanomedicine approaches help improve the organ quality and expand the donor pool. Moreover, advanced nanocarriers have been innovatively applied to optimize immunosuppressive therapy by enhancing solubility and bioavailability of poorly soluble drugs including FK506 and RAPA. Through targeted design, nanocarriers help achieve localized drug accumulation at the graft site, effectively reducing systemic drug exposure and improving drug safety.

3.1 Fundamental design principles for nanomedicine in organ transplantation

Nanomedicine is a drug delivery system in which active pharmaceutical ingredients are encapsulated within nanoscale carriers. Drugs are loaded onto these nanocarrier systems through encapsulation, adsorption, or chemical bonding to realize targeted drug delivery and responsive activation to specific stimuli [52]. Compared with traditional pharmaceutical formulations, a high specific surface area of nanomedicine enhances the bioavailability of a barely soluble drug and protects the active component from premature degradation. They can be actively or passively deposited in diseased tissues or in certain cells through functional alterations and, therefore, toxic by side effects on healthy tissues are reduced as much as possible [53]. Moreover, nanomedicine was also used in the noninvasive diagnostics to evaluate pathological conditions and therapy responses in real time [54]. Thus, nanomedicine undoubtedly has opportunities to improve the results of treatment and the quality of diagnostics, and the opportunities in the field of organ transplantation can be exploited to overcome the obstacles. Accurate and effective nanomedicine specific to organ transplantation can be designed through the employment of fundamental principles of design of nanocarriers.

The main design concept of the nanocarrier is to adjust physicochemical characteristics of its resulting nanomedicine to provide targeting delivery and homogenous distribution in the transplanted organs, such as size, surface charge, and functionality moiety alterations [55]. These properties are optimally useful in minimizing systemic exposures of the immunosuppressants to normal tissues. The size of nanomedicine is a very important factor in transplantation site as it travels through the biological barriers. For example, due to difference in microcapillary endothelial gaps in distinct organs, kidney (70-90 nm), liver (50-100 nm), and spleen (200 nm), nanomedicine that has been prepared at a given size range will easily traverse the respective capillary walls, thus increasing organ-specific accumulation [56]. It has been established that nanomedicine with very small size (less than 5mm) is rapidly excreted through the kidneys, but the large size (more than 200mm) of nanomedicine is readily taken up by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS). Thus, the optimization of off-target effects requires the optimization of the particle size [57]. Also, nanomedicine has an effect on delivery based on its surface charge. Nonspecifically binding of positively charged nanomedicine to cell membranes and neutral or slightly negative biosensing of nanomedicine surfaces have been observed to minimize protein adsorption and increase the circulation [58]. Additionally, the nanomedicine can be modified to include functional moieties that can help in advancing the precision of the immunosuppressant delivery. Indicatively, nanomedicine modification with polyethylene glycol (PEG) renders high effectiveness in extending the systemic circulation period [59]. Specific targeting ligands conjugation confers upon nanomedicine the capacity of accurately identifying and accumulating in particular organs or cell kinds thus enabling accurate immune modulation [60] (Figure 3).

Additionally, stimuli-responsive nanomedicine is highly beneficial in that it can react to endogenous or exogenous signals, and with specificity of the drug release process via regulated physicochemical changes. Diagnostic functions are combined with therapeutic functions in nanomedicine, which allows constant monitoring and regulation of the therapeutic intervention during the organ transplantation process [61]. As a summary, these general principles can help develop nanomedical designs useful in organ transplantation to reach the targeted, controlled drug delivery, integrated diagnosis and treatment. This approach synergistically enhances the efficacy of immunosuppression, protects transplanted organs from IRI, supports noninvasive monitoring and realizes personalized precision medicine after transplantation (Table 1).

3.2 Classification of nanocarriers for organ transplantation

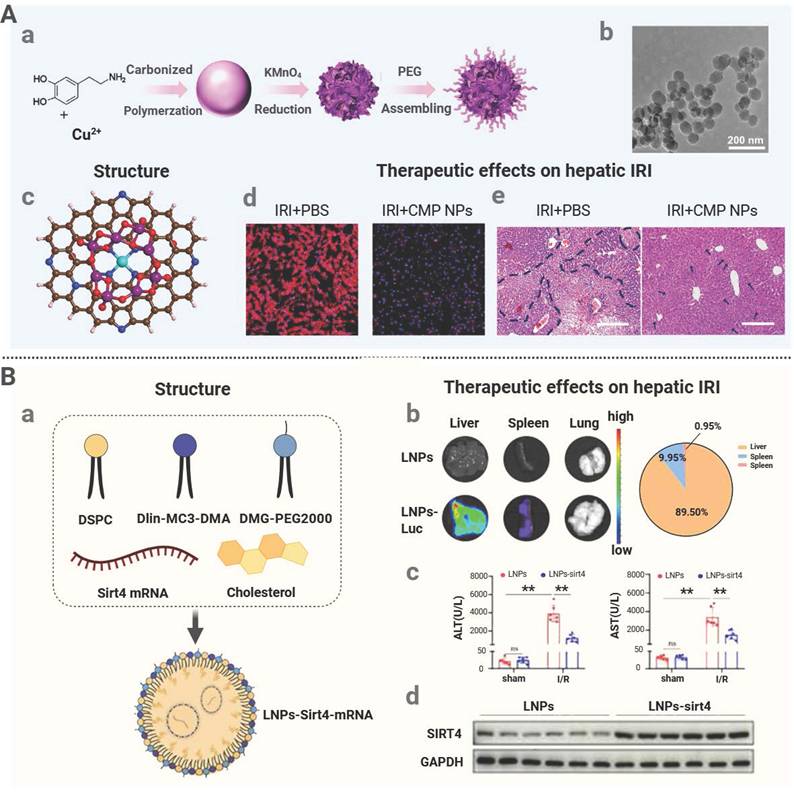

Nanomedicine used in organ transplantation can be classified into organic, inorganic, and hybrid nanomaterials according to their material composition and each category has distinct structural and therapeutic advantages. Organic nanomaterials, including polymeric nanoparticles and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), are highly biocompatible and biodegradable. Their surfaces can be readily functionalized with targeting molecules to achieve precise drug delivery [92]. The most representative polymer, PLGA, exhibits excellent biocompatibility and low immunogenicity. PLGA has been used to effectively encapsulate immunosuppressants and realize sustained drug release. For instance, Deng et al. developed FK506-loaded PLGA nanoparticles that helped prolong the survival of cardiac grafts in a rat model [62]. In addition, LNPs are composed of biocompatible lipids and their physicochemical properties can be precisely regulated. They have been employed to efficiently encapsulate and deliver nucleic acids, proteins, and small-molecule drugs to achieve potent targeted delivery. It has been recently reported that liver-targeting LNPs composed of an ionizable lipid SM102, DSPC, and cholesterol were applied to encapsulate SIRT4 mRNA via microfluidic technology. These LNPs increased the level of SIRT4, hindered ferroptosis, and decreased IRI following the liver transplantation [63]. PEG and polyacrylamide are organic polymeric coatings that enhance biocompatibility and extend systemic circulation and increase the therapeutic activity [93, 94]. Indicatively, PEG-ami-PEGylation was incorporated into an oligolycine surface to lower the non-specific uptake of nanoparticles by liver endothelial cells, which reduce clearance by the liver and enhance its targeting [64]. Natural polysaccharides are also good in the construction of nanomedicine since they are not toxic and immunogenic. The biomaterials include chitosan, hyaluronic acid, trehalose, dextran and heparin which are very cheap but are highly biocompatible naturally. They contain polysaccharides that facilitate the uptake into cells and allows the long release of the drug to be performed [95]. Nanohydrogels based on polysaccharides contain a three-dimensional crosslinked structure that has high water absorption and retention. They are composed of a similar material like one of a natural tissue and their application can result in a lower chance of immune rejection post-transplantation [96]. As an example, a porous chitosan amino acid hydrogel has been reported to be able to create a good sustenance of drugs release. It is a biodegradable and biocompatible hydrogel that can be used in delivery of drugs locally [65].

A framework for nanomedicine in transplantation. Nanomedicine in transplantation employs engineered nanomaterials (organic, inorganic, hybrid) and rational design to achieve precise targeting of lymphoid tissues, immune cells, and grafts by employing either active or passive strategies. Created with BioRender.com.

Nanocarrier design and composition in organ transplantation.

| NPs | Components of nanocarrier | Material type | Design strategy | Functional unit | Corresponding diseases | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA-FK506-NP | PLGA | Organic | Passive targeting | / | Cardiac allograft acute rejection | [62] |

| LNP | SM102, DSPC, cholesterol | Organic | Passive targeting | / | Liver IRI | [63] |

| PEG-OligoLys | PEG, oligo(l-lysine) | Organic | Passive targeting | / | / | [64] |

| CS-Lys/GP | Chitosan, αβ-glycerophosphate, l-lysine | Organic | Passive targeting | / | / | [65] |

| AuPt NPs | Gold, platinum | Inorganic | Passive targeting | / | Kidney IRI | [66] |

| PEI-arg@MON@BA | MON | Hybrid | Passive targeting | / | Liver IRI | [67] |

| AuNPs-Nanobody | Gold | Inorganic | Active targeting | VHH7 | / | [68] |

| heparin/CaCO3/CaP NPs | Heparin/CaCO3/CaP | Hybrid | / | / | / | [69] |

| M-NP | Macrophage membrane, PLGA | Hybrid | Active targeting | Toll-like receptor 4 | Liver IRI | [70] |

| FNVs@RAPA | Extracellular nanovesicles (E. C. grandis, mesenchymal stem cells) | Hybrid | ROS-responsive | Phenylborate ester bond (Azide precursor) | Heart transplant rejection | [71] |

| PEGylating 40 nm NPs | PS-COOH particles, PEG | Organic | Passive targeting | / | / | [72] |

| TA-FNP | PLGA | Organic | Active targeting | Tannic acid | / | [73] |

| PNIPAM-coated nanostructures | PNIPAM, polystyrene | Organic | Passive targeting | / | / | [74] |

| FK506 cochleates | PS70, cholesterol | Organic | Passive targeting | / | Heart transplantation rejection | [48] |

| aCD3/F/AN | Poly (γ-glutamic acid) | Organic | Active targeting | Anti-CD3e f(ab′)2 fragment | Melanoma | [75] |

| GG NP | Polymer gellan gum | Organic | Active targeting | Anti-CD3/CD28 | / | [76] |

| AuNP | Gold | Inorganic | Active targeting | mannose, galactose, fucose | / | [77] |

| Nanovesicles | Membrane (macrophage) | Hybrid | Active targeting | PD-L1/CTLA-4 | Skin and heart transplantation rejection | [78] |

| DPNP | DHA | Organic | Active targeting | DHA | Heart transplantation rejection | [79] |

| HATM | HA, 4-Methoxyphenyl thiourea | Organic | Active targeting/ROS-responsive | HA/TK linkage | Kidney IRI | [80] |

| GNP-HClm | Gold | Inorganic | Active targeting | HA | Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome | [81] |

| PEG-dendron | PEG | Organic | Ex vivo incubation | / | Islet transplant rejection | [82] |

| Polymeric NP | PLA-PEG | Organic | Active targeting | Anti-CD31 antibody | [83] | |

| PMON@Pt | MON | Hybrid | ROS-responsive | PBAP | Liver IRI | [84] |

| HRRAP NP | HA | Organic | PH-responsive | Hydrazone bond | Atherosclerosis | [85] |

| LNP | DODAP/gas vesicles | Organic | PH-responsive/ultrasound-responsive | DODAP | Heart transplantation rejection | [86] |

| PLG-g-LPEG/TAC | PEG, poly (l-glutamic acid) | Organic | Enzyme-responsive | Gly-Leu | Liver transplantation rejection | [87] |

| GBLI-2 | / | / | Enzyme-responsive | IEFD | colorectal carcinoma | [88] |

| UCNP@mSiO₂@SP-NP-NAP | Mesoporous silica | Inorganic | Light-responsive | Spiropyran, nitrobenzyl group | Heart IRI | [89] |

| MN-siRNA | Dextran, iron oxide | Inorganic | Magnetic-responsive | Iron oxide | Islet transplant rejection | [90] |

| sIONP | PEG, trimethyl silane, silica, IONP | Inorganic | Magnetic-responsive | Iron oxide | Organ rewarming injury | [91] |

NPs: nanoparticles; DSPC: 1,2-Distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; PEG: polyethylene glycol; MON: mesoporous organosilica; VHH7: MHCII Antibody; IRI: ischemia reperfusion injury; PLGA: poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid); PNIPAM: poly (N-isopropyl acrylamide); PS70: phosphatidylserine; PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; DHA: docosahexaenoic acid; DODAP: 1,2-Dioleoyl-3-dimethylammonium-propane; HA: hyaluronic acid; IEFD: Ile-Glu-Phe-Asp; IONP: iron oxide nanoparticle. LNP: lipid nanoparticle; PBAP: phenylboronic acid pinacol ester; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TK: thioketal.

The inorganic nanomaterials have unique benefits in transplantation of the organ as they are structurally rigid, stable and tunable [97]. Their pores and surfaces can be decorated to form artificial nanosystems that mimic an antioxidant nanoenzyme or can be used to carry a drug to modulate the immune system. As an example, Feng et al. designed gold platinum nanoparticles (AuPt NPs), which had a catalase-like activity and efficiently eliminated ROS to alleviate renal IRI during the transplantation procedure without any noticeable toxicity [66]. Gold nanoparticles are known for their low toxicity and biocompatibility. Their intrinsic safety can be enhanced through organic functionalization, and this functionalization process can also improve stability and biocompatibility of gold nanoparticles. Surface modification of gold nanoparticles with targeting ligands enables localized drug accumulation in transplant organs, supporting targeted therapy [98]. In a recent study, gold nanoparticles conjugated with an anti MHC class II antibody were selectively bound to MHC class II positive cells. Labelling of these particles with radioisotopes allowed PET/CT imaging, thus this platform could be used for post-transplant immune monitoring and targeted treatment [68]. Iron-incorporated nanomedicine, which has an iron-containing core, can be directed to transplanted organs under a magnetic field to reduce systemic toxicity of drugs in nanomedicine. They also act as an MRI contrast agent to allow real-time, noninvasive organ monitoring [99]. Additionally, iron-incorporated nanomedicine exhibits a magnetothermal property under an alternating magnetic field, and it can be harnessed for uniform rewarming of organs [100]. These properties support that the inorganic nanomedicine can be multifunctional to improve graft survival after combination of diagnosis and treatment.

Hybrid nanomaterials integrate diverse inorganic and organic components, such as metals, polymers, or biomolecules, to create nanoscale systems with novel composite structures. This approach overcomes the limitations of pure inorganic or organic systems, enabling enhanced functionality and broad application prospects [101]. An example is calcium phosphate (CaP), calcium carbonate (CaCO3) which has a high drug loading capacity. CaCO3 is degraded in a responsive manner in an acidic environment and controlled release of drugs can be done once CaCO3 has degraded [102]. The addition of heparin prevents aggregation of inorganic nanoparticles through steric hindrance and electrostatic repulsion and enhances their colloidal stability. Therefore, the heparin/CaCO₃/CaP hybrid nanoparticles could be used to build a stable drug delivery platform [69]. Another example is a biomimetic platform (PEI arg@MON@BA) prepared from degradable silica. Four functions including cfDNA adsorption, ROS clearance, calcium chelation, and NO release were integrated in this platform to significantly reduce IRI in rat and human liver samples [67]. Furthermore, by incorporating unique functions from natural biological components, hybrid nanomaterials demonstrate significant advantages in the field of organ transplantation, including low immunogenicity, excellent biocompatibility, and active targeting capabilities. Two representative biomimetic nanomaterials are cell membrane-coated nanoparticles and extracellular vesicles. Cell membrane-coated nanoparticles retain the properties of the membranes of their source cells. For example, a protective effect of macrophage membrane-coated nanoparticles (M-NPs) against liver IRI was demonstrated in a rat orthotopic liver transplantation model [70]. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) from macrophage membranes was preserved on these M-NPs, and it specifically neutralized the endotoxin LPS and suppressed LPS-induced macrophage activation. The macrophage membrane coating also helped migration of the nanoparticles into inflamed areas while improving biocompatibility and immune evasion. Innovative multifunctional fusion extracellular vesicles (FNVs@RAPA) were developed to treat early IRI and immune rejection after heart transplantation [71]. These vesicles were created by fusing nanovesicles (ENVs) from Aurantium chinensis with mesenchymal stem cell membrane-derived nanovesicles (CNVs) with overexpressed calreticulin (CALR), and the formed functional carriers were used for RAPA delivery. Plant-derived ENVs displayed low immunogenicity in animal models. They contained a myriad of miRNAs and anti-inflammatory molecules that could provide antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects during the organ transplantation process. Meanwhile, CNVs retained the immunomodulatory function and they could target macrophages.

Although few nanomedicines are currently clinically used in organ transplantation, the nanocarriers for nanomedicine have advantages of diverse types, functional integration, and favorable biosafety, and the resulting nanomedicine could be clinically applied for targeted therapy for transplanted organs, immune microenvironment regulation, and injury repair.

3.3 Targeting strategies of nanomedicine for organ transplantation

Traditional organ transplant therapies suffer from toxic side effects of systemic immunosuppression. Targeted nanomedicine delivery can improve the precision of immunosuppressant delivery, thus enhancing both safety and efficacy. The spleen and lymph nodes play central roles in transplant immunology. The spleen, the largest lymphoid organ, contains diverse immune cells that regulate systemic immunity. Lymph nodes function as hubs for adaptive immunity and coordinate T cell activation and immune surveillance. The spleen and lymph nodes are critical in both rejection and tolerance after transplantation. Consequently, targeted delivery of immunomodulators precisely to the spleen and lymph nodes can reduce their side effects and enhance their therapeutic efficacy. Nanomedicine possesses two categories of principles of targeting, including passive and active targeting. Passive targeting is contingent on the size and surface characteristics of the nanocarriers and natural localization of nanomedicine into organs or locations might be attained by passive targeting. As an example, the MPS identifies some nanoparticles in its natural state, and it may be concentrated in the immune organs, e.g. the thymus and lymph nodes [103]. Active targeting, in its turn, would entail altering nanomedicine in the form of targeting ligands. These ligands have the ability to personally identify receptors on involved organs or cells and bind, and this significantly improves the delivery accuracy and efficacy [104].

The stromal cells, the medullary cells, and the lymphocytes are found in lymph node (LNs) which are secondary immune organs [105]. They possess connective tissue capsule and comprise of cortex as well as medulla. The outer cortex contains the B cells and the inner paracortex is where T cells, DCs, and high endothelial venules (HEVs) which give access to lymphocytes via blood vessels. B cells, plasma cells and macrophages are found in the cords in the medulla and sinuses are filtered by the medulla. Lymph goes in the conduits and sine to facilitate contact between the antigens and the immune cells. On reaching the local LNs through lymph, transplant derived antigens stimulate allogeneic T cells thereby causing an immune response against the graft [106]. Nanomedicine is capable of being used to specific LN structures and cells and this mode has come to be one of the major strategies of reducing rejection. Nanomedicine is generated by targeting lymph nodes, and the size of the particles plays a major role in the delivery process. McCright et al. reported the successful accumulation of PEG-modified nanoparticles (40 to 100nm) in lymph nodes four hours following intradermal injection, which was due to their increased hydrophilicity and lower clearance. Particles of high-density PEG coating (40 nm) showed the greatest rate of accumulation in lymph nodes amongst them [72]. The specificity of nanomedicine is further enhanced following the incorporation of special ligands of targeting. Qiu et al. constructed the tannic acid-conjugated nanocarrier (TA-FNP) which was able to interact with the elastin of endothelium lymphatic. This carrier is a carrier that has FK506 and it is loaded in the carrier at a size of around 86 nm that is used to deliver FK506 to the lymph node. TA-FNPs infiltrated lymphatic endothelial junctions in the paracortical region to release FK506 to suppress T-cells activation and multiplication. In a heart transplant model, this system significantly reduced T-cell infiltration into grafts and prolonged graft survival [73].

The spleen is the largest peripheral immune organ in the body and contributes to immune responses and blood filtration. Its parenchyma consists of white pulp, red pulp, and a marginal zone between them [107]. The white pulp, organized around the central artery, is the main site for lymphocyte accumulation and immune activity. It contains the periarterial lymphatic sheath predominantly populated with T cells and lymphoid follicles enriched with B cells. The majority of the splenic parenchyma is composed of the red pulp which is constituted with a splenic cord and sinusoids. The splenic cord is a reticular structure containing rich macrophages, plasma cells, and blood cells, and it plays an important role in removing old red blood cells and capturing foreign particles from the blood. Splenic sinuses are specialized venous structures with gaps of about 200-500 nm wide, allowing slow passage of blood cells and capture of macrophage-mediated particles. The marginal zone has a clear organisation having numerous macrophage DCs and B cells. In the area, lymphocytes are activated by antigens in blood that is carried in the blood [108].

The spleen plays a role in graft damage during transplant rejection through antigen capture, T cells activation and antibody production of the donor antigens. The spleen has become a vital object of nanomedicine because of its primary location in immunity. Nanocarriers can be designed for splenic accumulation through precise control of the particle size and tuning of surface properties. For example, nanoparticles at a size of larger than 200 nm or those with hydrophilic coatings have exhibited enhanced splenic retention [109]. However, uptake of these nanoparticles by hepatic Kupffer cells has frequently diminished the effectiveness in their splenic delivery. To address this impediment, approaches including hydrophilic coatings, biomimetic modifications, and non-spherical designs have been developed to help reduce liver clearance and improve splenic targeting [107]. Gu et al. compared the distribution of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM)-coated nanostructures with different morphologies in mice, including spheres, rods and rings [74]. Non-spherical particles exceeding 400 nm, particularly rods and rings, accumulated preferentially in the red pulp, which could be ascribed to structural constraints of splenic sinusoids with 200-500 nm endothelial gaps. To apply this discovery in transplant immunosuppression, an FK506-loaded nanospiral composed of phosphatidylserine (PS70) and cholesterol was developed for targeting the spleen and lymph nodes [48]. The anionic PS70 component promoted uptake by mononuclear phagocytes. This nanospiral helped elevate the FK506 level in both the spleen and lymph nodes. This nanomedicine displayed precise targeting, high efficacy, and great safety over conventional formulations and it could be promising as a novel immunomodulatory candidate for transplantation.

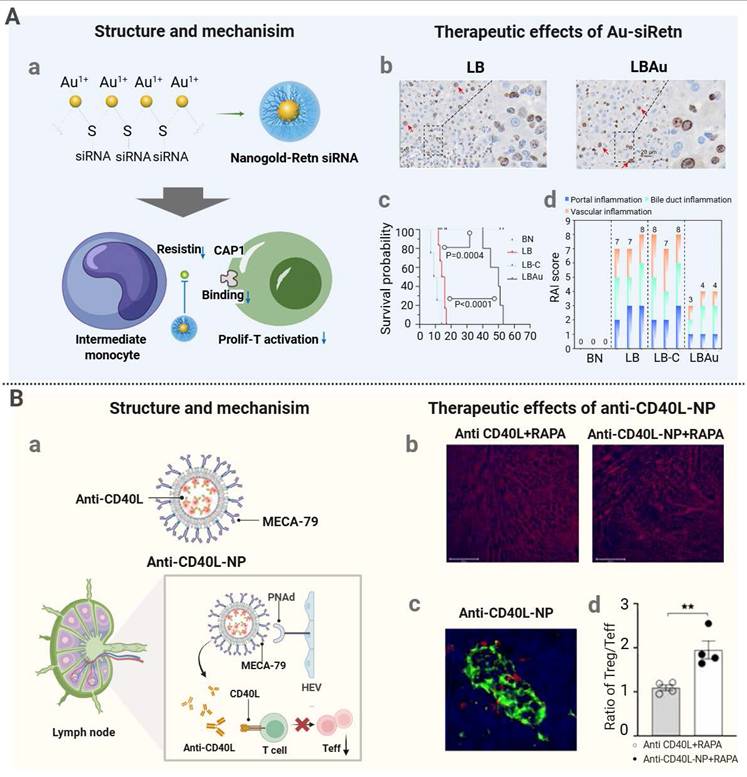

Besides acting on immune organs, nanomedicine also has the ability to regulate immune responses through the specific targeting of immune cell populations, e.g. T cells, DCs, and macrophages. This strategy enhances the effectiveness of transplant rejection treatment besides decreasing systemic toxicity [110]. Considering that T cells are the key actresses of graft rejection, T cell-based active targeting interventions raise special interest. Through surface functionalization with antibodies or ligands against targets on T cells such as PD-1 or CD3, nanomedicine can overcome the nonphagocytic nature of T cells and enable efficient drug internalization and release [111]. For instance, Kim et al. developed anti-CD3 antibody fragment-modified nanomedicine (aCD3/F/ANs) to enhance T cell targeting through CD3-specific binding and active internalization [75]. It was confirmed that aCD3/F/ANs, via their surface antibodies, significantly enhanced T-cell-mediated active internalization by specifically binding to CD3, a key component of the TCR complex. A gellan gum-based nanogel (npGG) conjugated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies was developed. This system mimicked activation of natural T cell receptors, providing a novel strategy for intervention of transplant rejection [76].

DCs, principal APCs, regulate transplant rejection and immune tolerance by controlling T-cell activation. Nanomedicine can deliver immunomodulators to DCs through targeting molecules on the surface, such as specific sugar ligands or antibodies. This approach can promote DC maturation and enhance antigen presentation, thereby strengthening regulatory DC induction to suppress allogeneic immune responses [112]. For example, AuNP modified with mannose, galactose and fucose at 30 different combination ratios to target C-type lectin receptors highly expressed on DCs. These monosaccharide-coated nanoparticles achieved precise delivery of immunosuppressive agents, and displayed significant potential in improving immune tolerance and reducing rejection [77]. In addition, Xu et al. integrated genetic engineering with nanotechnology to construct dual-targeted nanovesicles to target T cells expressing both programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4). These nanovesicles simultaneously inhibited T-cell activation by PD-1/PD-L1 interaction, they blocked CD28 costimulatory signals by CTLA-4/CD80 interaction on DCs and suppressed DC antigen presentation leading to synergistic immune suppression [78].

Macrophages dominate IRI and rejection and have now become a fundamental focus of nanomedicine designs. Nanomedicine provides an opportunity to modulate the macrophage activity and thereby reduce cell inflammation, inhibit proinflammatory molecules, and improve the graft survival [113]. Ligand modification can be done using nanocarriers with active targeting. An mTOR inhibitor, PP242, was conjugated to a prodrug nanoparticle (DPNP) by means of conjugation to the docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). DHA was effectively absorbed by the macrophages through lipid metabolism pathways hence promoting effective uptake of drugs and dramatically increasing the lifespan of cardiac grafts [114]. In addition to ligand modification, biomimetic nanocarriers, including mesenchymal stem cell membrane-based ones, can be macrophage-specifically targeted using the natural membrane proteins coupled with enhanced drug delivery efficiency to injury sites [71]. M2 macrophages upregulate receptors like CD44 and interaction between hyaluronic acid (HA) and CD44 triggering clathrin-mediated endocytosis and achieves specific delivery [80]. By harnessing this mechanism, a HA-coated nanoparticle (HATM) was designed to actively target M2 macrophages and renal tubular epithelial cells in IRI-affected kidneys, and its accumulation was pronounced in inflamed tissues. Therefore, macrophage-targeting nanomedicine has shown therapeutic potential for renal IRI [71].

Nanomedicine can be engineered to deliver therapeutic agents precisely to transplanted organs to enhance organ protection and functional recovery. For instance, Yu et al. utilized LNPs at a size of approximately 100 nm to achieve passive hepatic accumulation through hepatic sinusoids with high permeability. These LNPs were endocytosed by hepatocytes to deliver encapsulated SIRT4 mRNA to mitigate hepatic IRI [63]. It was shown that distinct hepatic accumulation at 24 hours after administration, with minimal distribution to the spleen and lungs, confirming effective liver targeting by LNPs. In another investigation, Pandolfi et al. developed a targeted nanomedicine, GNP-HClm, by loading imatinib onto AuNPs functionalized with anti-CD44 antibody fragments to treat bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation [81]. GNP-HClm was bound to CD44 glycoprotein highly expressed on fibroblasts to realize active targeting. This strategy resulted in an elevation in the drug level at lesion sites, and the released drug exerted significant antifibrotic and immunomodulatory effects in vivo.

In addition to in vivo targeted therapy, nanomedicine can be employed for precise intervention in donor organs during ex vivo perfusion. It has been documented that a dendritic polyethylene glycol (PEG-dendron) nanomaterial, which can adhere to a pancreatic islet surface to achieve localized immunosuppression after release of the immunosuppressive drug in the nanomaterials, thereby improving islet transplant survival in a diabetic model [82]. When the nanomaterial was incubated with isolated islets, the NHS ester groups on PEG-dendron formed covalent bonds with amino groups on islet cell surface proteins to create a physical barrier that reduced immune recognition. Additionally, normothermic machine perfusion can be served as a delivery platform for localized nanotherapy. Tietjen et al. developed poly (lactic acid)-polyethylene glycol (PLA-PEG) nanoparticles functionalized with anti-CD31 antibodies, and the nanoparticles specifically bound to CD31 molecules on renal vascular endothelial cells [83]. When administered during ex vivo perfusion, these nanoparticles accumulated effectively in renal endothelial cells, and efficient targeted therapy was achieved in donor organs.

3.4 Stimuli-responsive strategies for nanomedicine in organ transplantation

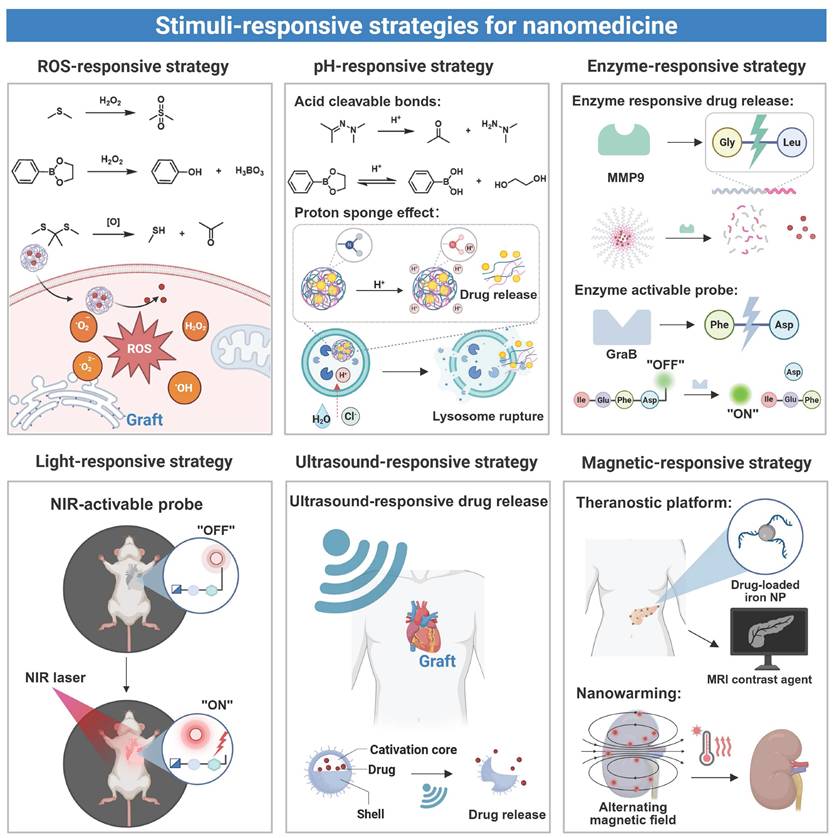

Endogenous stimuli-responsive design of nanomedicine is based upon biochemical changes within an inflammatory microenvironment of grafts, and the stimuli trigger drug release from the nanomedicine through mechanisms including bond cleavage or carrier transformation [115]. Exogenous stimuli-responsive nanomedicine undergoes physicochemical changes upon exposure to external sources like light, a magnetic field, or ultrasound, allowing precise spatiotemporal control over drug delivery and activation. Both approaches have been demonstrated to improve therapeutic delivery precision and enhance diagnostic sensitivity/accuracy during transplantation [116] (Figure 4).

In organ transplantation, IRI or immune rejection often leads to reactive oxygen species accumulation, a decrease in pH, and an elevation in the expression level of certain enzymes. These endogenous signals have been acted as molecular triggers to stimulate nanomedicine to release loaded therapeutic agents at the lesion site. This localized delivery strategy reduces systemic drug exposure and minimizes off-target effects. The ROS-responsive nanomedicine has been developed to achieve targeted drug release in response to ROS at an abnormally elevated level in a pathological microenvironment. In this type of nanomedicine, specific chemical bonds, such as sulfur-containing or ester linkages, undergo cleavage upon interaction with ROS [117]. ROS-responsive nanoplatforms for targeted drug delivery have been applied in transplantation. For example, a drug delivery platform (PMON@Pt) based on a mesoporous organosilica system (MON) was developed by incorporating tetrasulfide bonds and surface-functionalized phenylboronic acid pinacol ester. In a high-ROS microenvironment of liver IRI, this nanoplatform underwent degradation through boronic ester cleavage and matrix disruption, achieving efficient release of platinum nanoparticles [84]. In another study, a chitosan-based nanoplatform modified with phenylboronic ester was developed for the delivery of myricetin [118]. The phenylboronic ester acted as a ROS-responsive linkage, which underwent specific oxidative cleavage after exposure to a high level of H₂O₂ present in hepatic IRI, thereby triggering rapid release of myricetin. The released drug effectively exerted antioxidant effects and promoted the repair of damaged vascular endothelium. Similar results were found in HATM micelles which employed thioketone (TK) linkages to achieve selective drug release at renal IRI sites [80]. In addition, a ROS-responsive azide-glycoside precursor (ROS-N₃) connected via phenylboronic ester bonds was developed. Upon H₂O₂ exposure, an azide group that was anchored on cell membranes was exposed in the cleaved product, enabling subsequent bioorthogonal conjugation with dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-modified nanovesicles for site-specific drug delivery after heart transplantation [71]. These strategies collectively demonstrate the therapeutic potential of ROS-responsive nanomedicine during the transplantation process.

pH-responsive nanomedicine achieves targeted drug delivery by harnessing the pH difference between inflamed sites and their neighboring healthy tissues. Transplant rejection creates a localized acidic microenvironment, while normal tissues maintain a neutral pH, and the pH difference can be explored for selective drug release from nanomedicine [119, 120]. pH-response mechanisms include protonation-induced charge changes, alterations in hydrophobic interaction, and cleavage of acid labile bonds [121]. Nanocarriers maintain a neutral or negative surface charge during circulation, and their surface charge is changed to be positive in an acidic region, improving their binding to target sites. Don et al. developed a pH-responsive nanomedicine through self-assembly of chitosan and fucoidan to deliver curcumin [122]. The carrier response mechanism was contingent on the protonation state of the amino groups of chitosan under a specific pH condition. In a physiologically neutral environment, the amino groups remained deprotonated, whereas the amino groups protonated and acquired a positive charge upon entering an acidic microenvironment of an inflamed site. The positive surface charge of the nanomedicine enhanced its interaction with negatively charged inflammatory cells, facilitating cell binding and endocytosis. In addition to the charge reversal mechanism, another prevalent approach to achieving pH-responsive release involves the utilization of acid-labile chemical bonds (e.g., ester, hydrazone, or hydrazine bonds). A recently developed hyaluronic acid-based pH-responsive nanoparticle (HRRAP NP) achieved codelivery of all-trans retinoic acid (ATR) and RAPA [85]. All-trans ATR was conjugated to HA through a hydrazone bond, and the resulting conjugate self-assembled into nanoparticles. During the self-assembly process, RAPA was encapsulated in the hydrophobic core of nanoparticles. Under an acidic inflammatory condition, cleavage of the hydrazone bond triggered nanoparticle disassembly, realizing simultaneous drug release. These nanocarriers often contain weakly basic groups, such as imidazole or amino moieties, to strengthen the proton sponge effect. During lysosomal acidification, these weakly basic groups absorbed protons, and the osmotic pressure was increased to cause lysosomal rupture and facilitate cytoplasmic drug release [123]. In another example, a pH-responsive lipid nanoparticle was designed for microRNA delivery [86]. An ionizable lipid, DODAP, was employed in this nanoparticle, and it maintained neutrality at a physiological pH to minimize nonspecific clearance and extend the circulation time. Upon entering acidic lysosomes in cardiomyocytes, the tertiary amine group of DODAP underwent protonation, enhancing the endosomal escape efficiency and promoting cytoplasmic release of microRNA to treat post-transplant rejection.

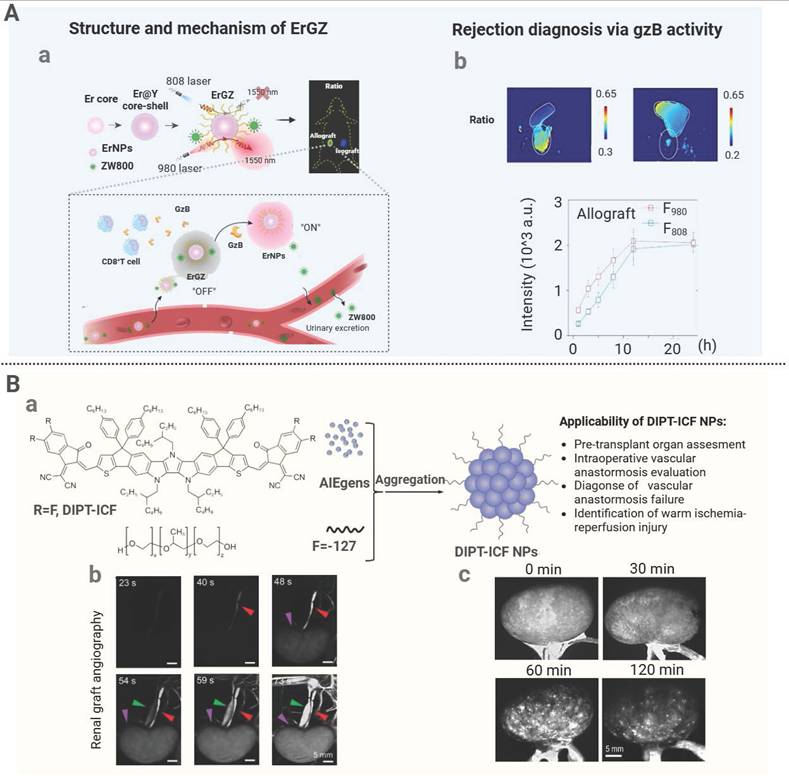

Enzyme-responsive nanomedicine undergoes structural changes after exposure to overexpressed enzymes in the transplant microenvironment to achieve localized drug release [124]. For instance, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), upregulated during liver transplant rejection, accelerated degradation of extracellular matrix components [125]. By harnessing this mechanism, Luo et al. developed an MMP9-responsive delivery system (PLG-g-LPEG/TAC) for targeted TAC release to treat acute liver rejection [87]. When nanoparticles accumulated in the rejected liver tissue, upregulated MMP9 cleaved the Gly-Leu peptide bond to trigger micelle dissociation and rapid TAC release. This approach improved the liver function and survival in a rat model. Additionally, to target granzyme B (GraB) expressed in inflammatory lesions, a bioluminescent probe (GBLI-2) was designed by conjugating a specific substrate IEFD with D-fluorescein. Cleavage of the bond between IEFG and D-fluorescein by GraB resulted in release of D-fluorescein and generation of light signals. This approach allowed sensitive monitoring of the GraB activity for real-time detection of immune activation and rejection after transplantation [88].

Externally activated nanomedicine can be precisely controlled for drug release to improve both therapeutic efficacy and safety. Light is a commonly used external stimulus, and it can induce structural changes in nanocarriers through photocleavage or photoisomerization mechanisms [126]. Photoresponsive nanocarriers are stimulated by two types of light at different wavelengths: short-wavelength light (UV-visible, 100-780 nm) and near-infrared light (NIR, 780-1400 nm). Short-wavelength light displays a short tissue penetration depth, triggers premature drug release and induces tissue damage [127], while NIR allows deep penetration with reduced phototoxicity, and it has been employed to target large transplanted organs, such as kidneys, livers, and hearts [128]. The majority of current light-responsive nanomedicines are activated by short-wavelength light because chemical bonds in these nanomedicines show weak response to NIR. To address this issue, a NIR-activated dual-responsive nanoprobe (UCNP@mSiO₂@SP-NP-NAP) was designed for simultaneous detection of hydrogen polysulfide (H₂Sₙ) and sulfur dioxide (SO₂) in myocardial IRI [89]. This dual-responsive design allowed dynamic, simultaneous monitoring of both SO₂ and H₂Sₙ, enabling precise assessment and real-time visualization of IRI in transplanted organs.

Ultrasound responsive nanomedicine utilizes the deep penetration and noninvasive properties of ultrasound for targeted drug delivery to transplanted organs [129]. This is done through conversion of acoustic energy to localized pressure variations to cause microbubble oscillation and collapse, which cause very strong mechanical stresses and specific thermal effects on nanomedicine, which contributes to the integrity disruption of nanomedicine. Indicatively, some impacts of ultrasound-induced cavitation are high local forces that enhanced targeted delivery of drugs in nanodroplets [130]. A specific method of delivery encapsulating the microRNA (antagomir-155) in LNPs was designed. The ultrasound was low-intensity and used to cause the gas vesicle (GV) cavitation which showed promising effectiveness in cardiac transplant rejection therapy [86]. The collapse of ultrasound-induced GVs led to microflows and mechanical shear forces, which raise the vascular endothelial permeability to allow LNPs to extravasate into the myocardial tissue and extends cardiac allograft survival dramatically.

Stimuli-responsive strategies for nanomedicine in transplantation. Endogenous triggers (ROS, pH, enzymes) and exogenous stimulus (light, ultrasound, magnetic fields) are harnessed to enable controlled drug release and activate nanoprobes at targeted sites. Created with BioRender.com.

Nanomedicine based on magnetic response can be a major benefit in organ transplantation treatment of functional imaging, targeted drug delivery, and controlled and consistent heating. The nanomedicine can be directed to a transplantation site using magnetic guidance with improved and localized accumulation of immunosuppressive agents or imaging agents. The magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles have been used as an efficient MRI contrast agent and they provide noninvasive and real time division of the graft functionality and mapping of the nanomedicine so as to enhance the sensitivity and precision in postoperative assessment [131]. Also, it is further proposed that, under alternating magnetic field (AMF), magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles produce localized heating and can be used to perform a focused thermal procedure without the dangers of employing the thermal temperature of an entire organ [132]. Already, more sophisticated combined magnetic targeting, imaging, and nanowarming is being developed to provide complete transplant organ protection and monitoring. As an example, Robertson et al. used siRNA-conjugated magnetic nanoparticles to label the isle [90]. Iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) can be used as effective nanowarming agents. When they are uniformly dispersed in organs via perfusion, IONPs generate heat at an equivalent level in the organ under an AMF, reducing ice crystal formation and thermal stress during rewarming. Gao et al. developed silica-coated IONPs (sIONPs) for homogeneous perfusion and effective clearance in rat kidneys [91]. By coating commercial EMG308 IONPs with silica and modifying them with PEG and trimethoxysilane (TMS), the nanoparticles maintained a high heating efficiency under an AMF (360 kHz, 20 kA/m) while preserving colloidal stability in cryoprotectants. In rat kidney perfusion models, sIONPs were distributed evenly through glomerular capillaries without causing vascular obstruction, demonstrating sIONPs could be a promising low-damage nanowarming agent for transplant organs.

Although single-stimulus systems have been used to establish a basis of responsiveness, multi-stimuli-responsive protocols to improve targeting precision have been used with increasing frequency. Multi stimuli-responsive approaches have a valuable benefit in combining endogenous stimuli (pH, ROS and enzyme activity). The multi-stimulus systems will be in a position to deal with the overall heterogeneity of the environment following transplantation, thereby minimizing off-target release significantly. It is also possible to augment spatiotemporal accuracy of drug delivery through additional delivery of exogenous stimulus that may be magnetic fields, light or ultrasound and to reduce interindividual differences. Additionally, sequential response mechanisms which are reached through administration of several stimuli in a given sequence makes sure that there is site and stage specific activation of drugs at the end of a series of required biological responsive stages [137]. Although that is early in the development of the mold of organ transplantation use, this strategy has a huge potential in precise therapy. To speed up the clinical translation of this system, the multi-stimuli system may be combined with particular targeting needs of transplant immunology to enhance it.

4. Advances in nanomedicine application for organ transplantation

In pretreatment, nanomedicines enhance graft quality through uniform nanoparticle-enabled rewarming, which reduces cryopreservation injury and IRI, as well as through integration with ex vivo perfusion systems. Perioperatively, nanocarriers deliver therapeutic agents to injury sites to clear reactive oxygen species and mitigate inflammation. In post-transplantation, nanomedicines enable targeted immunosuppression, improving treatment efficacy while minimizing off-target effects and supporting immune tolerance. Additionally, nanotechnology contributes to early diagnosis and theranostic applications, thereby facilitating continuous monitoring and adaptive treatment throughout the transplantation process (Table 2).

4.1 Nanomedicine for donor organ preconditioning

Donor organ pretreatment during the interval between procurement and transplantation is often conducted through mechanical perfusion, and nanomedicine can be incorporated into the perfusion process. The drug concentration within the target organ is elevated via the localized nanomedicine delivery approach and systemic circulation of the nanomedicine is circumvented, thereby reducing clearance and off-target effects [29]. Since the donor organ remains isolated during perfusion, direct delivery of immunosuppressants in nanomedicine prevents systemic immune interference and contributes to a reduction in the reliance on postoperative high-dose immunosuppressive regimens [163].

The integration of immunosuppressant-loaded nanomedicine into NMP is currently actively explored. For instance, PEG-PLGA nanoparticles were employed to deliver mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) for donor heart pretreatment, successfully reducing posttransplant vascular lesions [133]. MMF, an immunosuppressant, inhibits purine synthesis in lymphocytes via blockade of inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), thereby suppressing T-cell proliferation and exerting an anti-endothelial cell activation effect. Direct musical in a model of murine heart transplantation saw the retention of the MMF-loaded nanomedicine in the donor heart, and delivered sustained release of the drug without immunological effect systemically in the spleen or lymph nodes. This gave major effects in attenuation of the early inflammation, vascular injury and fibrosis and better graft-long term survival. This ex vivo nanotechnology platform achieved localized immunosuppression to the graft site, thereby preventing chronic rejection and reducing systemic potential risks (e.g., infection and malignancy).

Applications and efficacy of nanomedicines in organ transplantation.

| NPs | Material type | Design strategy | Drug | Corresponding disease | Results | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMF-NP | Organic | Ex vivo perfusion | Mycophenola-te mofetil | Heart transplantation rejection | Suppressing early post-transplant inflammation. | [133] |

| CoQ10@TNPs | Hybrid | Ex vivo perfusion/active targeting | CoQ10 | Heart IRI | Significantly suppressing mitochondrial ROS generation and enhancing cardiac function post-transplantation. | [134] |

| SPIONs | Inorganic | Magnetic-responsive | / | Organ rewarming injury (heart, islet) | Successfully rewarming the organ (heart, islet) after cryopreservation | [135, 136] |

| sIONP | Inorganic | Magnetic-responsive | / | Organ rewarming injury (kidney, liver) | Reducing rewarming injury in cryopreserved organs (kidney, liver) by nanowarming. | [137-139] |

| n(SOD-CAT) | Organic | Passive targeting | SOD, CAT | Liver IRI | Suppressing apoptosis and mitigating histopathological damage in IRI-induced liver injury. | [140] |

| Cuus-pC@MnO₂@PEG | Inorganic | Passive targeting | / | Liver IRI | Effectively suppressing ROS accumulation and concurrently reducing hepatocyte necrosis. | [141] |

| BX-001N | Organic | Passive targeting | Synthesize bilirubin 3α | Kidney IRI | Suppressing early post-transplant inflammation. | [142] |

| Nano-taurine | Inorganic | Active targeting | Taurine | Liver IRI | Exhibiting superior efficacy and safety over free bilirubin in a renal IRI model. | [143] |

| MOFSP | Hybrid | / | Salidroside | Heart IRI | Selectively accumulating in hepatic IRI sites and demonstrating a significant hepatoprotective effect. | [144] |

| hUC-MSC-Evs | Organic | Active targeting | Mitochondria | Liver IRI | Providing localized, sustained drug release and thereby alleviating cardiac IRI. | [145] |

| NP-Ly6G(2-DG) | Organic | Passive targeting | 2-DG | Liver IRI | Restoring the neutrophil mitochondrial function and ultimately alleviating liver IRI | [146] |

| LNPs-sirt4 mRNA | Organic | Passive targeting | SIRT4 mRNA | Liver IRI | Mitigating pulmonary IRI by suppressing neutrophil glycolysis. | [63] |

| aNP | Organic | Active targeting | Tacrolimus | Skin transplantation rejection | Suppressing ferroptosis and consequently alleviating hepatocyte death. | [147] |

| Tac-NP-CD4Ab | Inorganic | pH-responsive | Tacrolimus | Kidney transplantation rejection | Effectively preventing rejection and mitigating nephrotoxicity risk of tacrolimus. | [148] |

| Ce6-NP-MCP-1 | Organic | Active targeting/Ultrasound-responsive | Ce6 | Heart transplantation rejection | Inhibiting B cell plasmacyte differentiation and DSA production and reducing conventional drug nephrotoxicity. | [149] |

| AU-siRetn | Inorganic | Passive targeting | siRetn | Liver transplantation rejection | Depleting macrophages, reducing inflammatory cell infiltration in the cardiac allograft, and prolonging recipient survival via sonodynamic therapy. | [150] |

| C5 siRNA-LNP | Organic | Passive targeting | C5 siRNA | Kidney transplantation rejection (ABMR) | Reducing inflammatory cell infiltration and T cell over-proliferation in the liver, and ameliorating the transplant liver function. | [151] |

| rPS | Organic | Passive targeting | RAPA | Islet transplantation rejection | Blocking excessive activation of the complement pathway, significantly prolonging graft survival, and improving the renal function. | [152] |

| FasL@Rapa NPs | Organic | Active targeting | RAPA | Islet transplantation rejection | Significantly suppressing T cell proliferative responses to donor antigens and maintaining normal blood glucose levels for 100 days in islet-transplanted mice. | [153] |

| BEZ235@NP | Organic | Passive targeting | BEZ235 | Heart transplantation rejection | Effectively suppressing CD8⁺ T cell proliferation, promoting Treg expansion, and prolonging transplanted islet survival. | [154] |

| FTY720@TNP | Hybrid | Passive targeting | FTY720 | Heart transplantation rejection | Prolonging the survival of mouse cardiac allografts, reducing the activation and infiltration of CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T cells, and increasing the Treg proportion. | [155] |

| MECA-79-anti-CD40L-NP | Organic | Active targeting | / | Heart transplantation rejection | Increasing the local Treg/Teff ratio in lymph nodes and thereby promoting long-term graft survival. | [156] |

| KSINPs | Inorganic | / | / | Islet transplantation rejection | Prolonging the survival of heart grafts to 80 days. | [157] |

| GBRNs | Inorganic | Enzyme-responsive | / | Heart transplantation rejection | Remodeling the splenic immune environment, and enabling long-term survival and function of transplanted islets. | [158] |

| ErGZ | Inorganic | Enzyme-responsive | / | Skin and islet transplantation rejection | Enabling early detection of rejection by GBRNs prior to significant functional loss in cardiac allografts. | [159] |

| MTBPB/GPs | Organic | ROS-responsive | / | Skin transplantation rejection | Enabling real-time monitoring of intragraft granzyme B activity with high sensitivity and specificity. | [160] |

| DIPT-ICF | Organic | / | / | Kidney transplantation complications | Enabling early detection of acute rejection and evaluation of immunosuppressive therapy efficacy. | [161] |

| APNSO | Organic | ROS-responsive | / | Liver injury | Achieving clear images of the vascular structure of the transplanted kidney, which can be used to assess the patency of the postoperative urinary tract anastomosis, vascular stenosis, and the degree of IRI | [162] |

| MN-siRNA | Inorganic | Magnetic-responsive | / | Islet transplantation rejection | Non-invasively assessing the severity of hepatic IRI by combining real-time in vivo fluorescence imaging with urine fluorescence intensity quantification. | [90] |

ABMR: antibody mediated rejection. CAT: catalase; IRI: ischemia reperfusion injury; NPs: nanoparticles; RAPA: rapamycin; ROS: reactive oxygen species; SOD: superoxide dismutase.

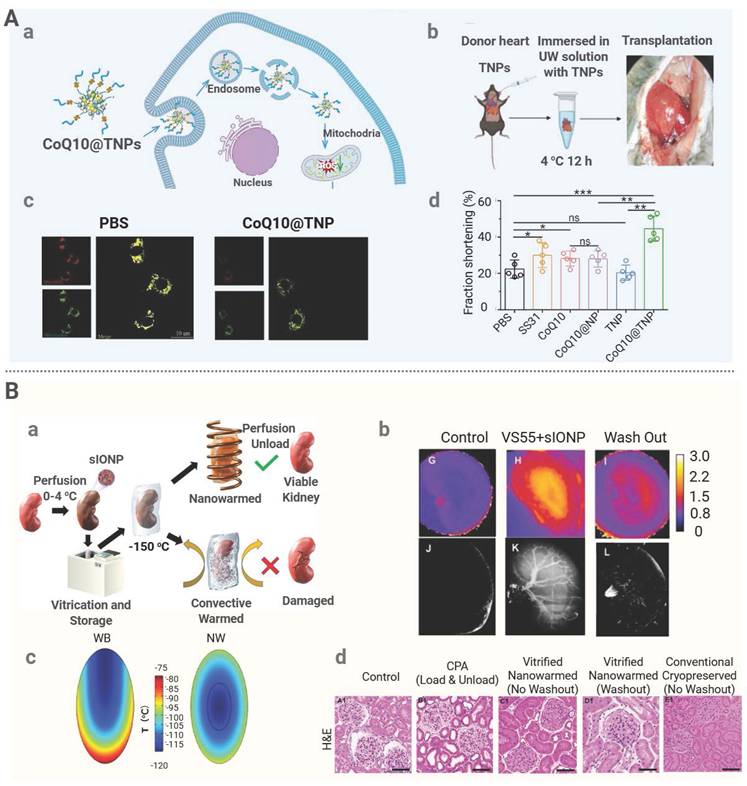

Yuan et al. developed a mitochondria-targeting nanomedicine system (CoQ10@TNPs) for donor heart pretreatment to mitigate IRI [134]. A coenzyme, Q10 (CoQ10), was encapsulated in composite nanoparticles composed of calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate, and biotinylated carboxymethyl chitosan, and surface modification of the composite nanoparticles was performed by introducing a mitochondrial-targeting peptide, SS31, to achieve organelle-specific delivery. It was demonstrated that during ex vivo preservation, CoQ10@TNPs administered via aortic perfusion preferentially accumulated in the donor heart mitochondria, which led to a significant reduction in mitochondrial ROS production, a decrease in oxidative damage, and suppression of apoptosis and inflammatory responses, ultimately improving the post-transplant cardiac function (Figure 5A). Another novel strategy was applied during donor organ preservation to avoid systemic immunosuppression by engineering the vascular endothelium of the donor organ with a glycopolymer, LPG-Q-Sia3Lac, during cold preservation. Through tissue transglutaminase-mediated conjugation, the polymer formed a stable barrier on the endothelial surface. The sialic acid residues on this barrier bound to Siglec receptors on immune cells, thereby suppressing the activation of NK and CD8+ T cells. This treatment significantly reduced early inflammation as well as acute and chronic rejection in aortic transplant models, while in kidney transplantation models, it markedly alleviated IRI and improved the renal function [164].

Nanomedicine can be employed for donor organ preconditioning during the rewarming phase after vitrification [165]. Magnetic nanoparticles, such as SPIONs or sIONPs, can be preinfused into organ vasculature prior to cryopreservation. Under an AMF, these nanoparticles generate internal heat for rapid and uniform rewarming, preventing ice crystal damage [166]. This approach has been validated across multiple biological models. For instance, a magnetic cryoprotectant (mCPA) composed of PEG-coated SPIONs and VS55 was developed [135]. This mCPA formulation achieved a heating rate of 321 °C per minute, far exceeding 50 °C per minute required for vitrification. Rat hearts cryopreserved for one week were able to fully recover structurally and functionally after mCPA-assisted rewarming. In another study, pancreatic islets were rewarmed with SPIONs at 5 mg/mL under an AMF and a warming rate of 72 °C per minute was achieved [136]. After transplantation into diabetic mice, these islets restored normoglycemia, whereas those thawed by water bath failed. These findings suggest nanowarming could enhance the tissue quality and improve the transplantation of complex tissues.

Additionally, a silica shell of sIONPs mitigates particle aggregation and sIONPs have low immunogenicity. Han et al. successfully conducted kidney transplantation in a rat model after the application of PEG-modified sIONPs in conjunction with a low-toxicity cryoprotectant, VMP [137]. It was shown that after sIONPs were uniformly distribution in the kidney, uniform and rapid internal rewarming of the organ was achieved under an AMF. The kidney cryopreserved up to 100 days regained its normal function after nanowarming. The key renal function indicators remained stable over a 30-day post-transplantation period, confirming the graft viability comparable to freshly transplanted kidneys. Similar results were obtained by Sharma et al. when they administered sIONPs in conjunction with a cryoprotectant into the kidney via vascular perfusion. Microcomputed tomography (μCT) and MRI confirmed uniform distribution of nanoparticles within the renal vasculature and both techniques were also used for real-time monitoring of organ vitrification [138]. Histological analysis revealed that the kidney cells in the nanoparticle-rewarmed group exhibited a high viability and preserved the endothelial structure, comparable to those in kidneys perfused with cryoprotectants alone without cryopreservation or rewarming (Figure 5B). The research team also investigated the efficacy of sIONPs in liver rewarming after cryopreservation. Under an AMF, sIONPs were stimulated to generate rapid (61 °C/min) and uniform heating. The rewarmed liver showed an intact tissue structure, preserved vascular endothelium, and substantially recovered the hepatocyte function [139]. Despite mild impairment for bile excretion and a slight increase in the alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, the overall damage to the treated organ was minimal.

Nanoparticle-based strategies for organ preconditioning. (A) Graft pretreatment to attenuate IRI. (a) Scheme of CoQ10@TNPs. (b) Schematic of a donor heart (DH) perfused with CoQ10@TNPs. (c) The MtROS content in H9c2 cells measured by MitoSOX staining. (d) Ejection fraction and fractional shortening of the cardiac graft on day 1 post-transplantation. Adapted with permission from [135], copyright © 2025 Springer Nature. (B) (a) Schematic of the kidney nanowarming process. (b) MR and µCT images for the distribution of sIONPs, which was based on the water relaxation rate constant. (c) Temperature distribution within a kidney section. (e) H&E photomicrographs of kidneys. Adapted with permission from [139], Copyright © 1999-2025 John Wiley & Sons, Inc or related companies.