13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(6):3105-3135. doi:10.7150/thno.126282 This issue Cite

Review

Stimuli-responsive hydrogels based on cascade reactions: a novel strategy to promote the efficient repair of diabetic wounds

1. School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Yantai University, Yantai 264005, Shandong Province, PR China.

2. Center of Plastic and Cosmetic Surgery, School and Hospital of Stomatology, China Medical University, Liaoning Provincial Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases, Shenyang 110001, Liaoning Province, PR China.

Received 2025-10-4; Accepted 2025-11-27; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

The impaired healing of diabetic wounds is caused by complex multifactorial pathologies and conventional therapeutic approaches often show limited efficacy. In recent years, stimulus-responsive hydrogels based on cascade reactions have become a promising approach in the management of diabetic wounds. These hydrogels are designed to react to particular characteristics of the wound microenvironment, such as glucose concentration, pH, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and enzyme activity, allowing spatiotemporally controlled drug release and synergistic multi-target control. This review focuses on the recent development in understanding of the pathophysiology of diabetic wounds, immune microenvironment modulation, and the development of stimuli-responsive cascade hydrogels, as well as the challenges. By integrating responsive moieties, these hydrogels dynamically control the polarization of immune cells and scavenging of ROS. Furthermore, cascade systems, from single-step to multistep design, enable precise spatiotemporal activation and coordinate antibacterial, antioxidant and pro-regenerative effects. Additionally, emerging technologies such as AI-assisted modeling, biosensing-guided feedback, and organ-on-a-chip platforms have great potential to improve the rational design and predictive validation of cascade hydrogel systems, paving the way for intelligent and personalized diabetic wound therapies.

Keywords: cascade reaction, hydrogel, responsiveness, diabetic wound

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic disorder that is spreading across the globe at an unprecedented rate. According to the international diabetes federation, the number of people suffering from diabetes is rapidly rising and is expected to reach almost 1.31 billion by 2050 [1]. Beyond greatly affecting the quality of life of patients, diabetes leads to many complications, such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, nephropathy, retinopathy and neuropathy, that impose a significant burden on the healthcare systems worldwide [2,3]. Among these complications, the wound healing of diabetics is a particularly formidable challenge, with a long healing process, risk of infection and a high rate of recurrence [4]. In severe cases, wounds may become chronic and non-healing and may lead to amputation.

The diabetic wound healing process is hindered by several interrelated factors including persistent inflammation, hyperglycemia, excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS), bacterial infections, hypoxia and other complex microenvironmental disturbances [5]. These obstacles hinder the normal repair cascade, thus highlighting the urgent need for efficacious therapeutic strategies against diabetic wounds. Wound dressings play an integral part in treatment and create an essential barrier and healing [6]. However, conventional dressings, such as gauze and foam, mostly maintain moisture and prevent bacterial contamination but are limited in their functional capabilities. They do not adequately address the multifaceted and dynamic microenvironmental alterations that are characteristic of diabetic wounds, and therefore do not adequately address the diverse and evolving needs of this patient population [5].

In the last few years, hydrogels have become a promising new class of wound dressings with a great potential in treating diabetic wounds. Hydrogels are composed of hydrophilic polymer networks that can absorb and hold large volumes of water, which in turn provides a moist environment that can enhance healing while minimizing bacterial colonization. Compared to traditional dressings, hydrogels more closely replicate the structure of the extracellular matrix (ECM) providing better cell adhesion and migration, which increases wound repair. Moreover, the high tunability of the hydrogels enables customization depending on the specific circumstances of the wound, which enables tailored treatment strategies to address diverse treatment requirements [7-9]. Stimuli-responsive hydrogels have attracted broad attention because of their intelligent, adaptive characteristics [10]. These hydrogels can react to external stimuli, such as pH, temperature, enzyme activity, or biomolecular signals, by changing their physical and chemical properties to adapt to the changing wound microenvironment. For example, pH-responsive hydrogels can respond to the acidic environment common to the inflammatory phase and release anti-inflammatory agents to reduce inflammation. Similarly, temperature-responsive hydrogels change their hardness or shape depending on the body temperature and hence can better conform to the wound contour [11-13]. These smart, stimuli-responsive behaviors facilitate active and enhanced hydrogel involvement in the wound healing process and provide novel strategies to handle diabetic wounds.

Cascade reactions are frequently found in biology as a series of consecutive chemical reactions, in which the product of one reaction is a catalyst for the next [14-15]. In tissue repair this concept has been exploited to design smart materials that can mimic these complex biological processes [16-18]. By integrating the responsive units into the hydrogel networks, the cascade reactions can be induced to experience a sequence of orderly transformations in response to specific stimuli, thus allowing the wound microenvironment to be precisely regulated.

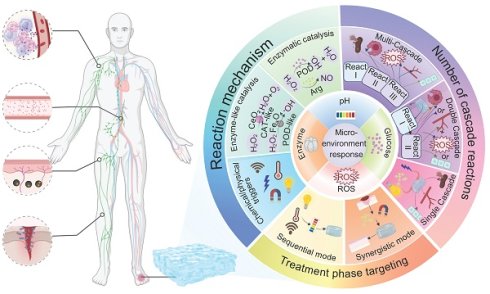

This review focuses on giving a comprehensive summary of diabetic wound pathology and wound therapeutic strategies, especially focusing on the recent progress of stimulus-responsive hydrogels based on cascade reactions. First, the pathophysiological process in diabetic wounds is explained and divided into four different stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling. Emphasis is placed on the important roles of macrophages and neutrophils in modulating the immune microenvironment during each stage as well as the relevant cell signaling pathways. Next, combining these cellular and molecular knowledge, several types of microenvironment-responsive hydrogels, such as glucose-, pH-, enzyme-, and ROS-responsive systems are discussed for their ability to enhance the local microenvironment by facilitating neovascularization, tissue repair, and immune regulation (Figure 1). Based on the source of stimulation, various cascade hydrogel systems have been developed, with most of the current models based on the principle of enzymatic cascade. Increasingly, dual or multi-step modules are used to improve the spatiotemporal precision. These approaches have a lot of benefits including enhanced catalytic efficiency and stability, especially in nanozyme mimicking systems, as well as enabling synergistic cascades to promote diabetic wound therapy towards complete and dynamic regulation. Finally, the review emphasizes outstanding challenges such as the development of intelligent materials that are able to dynamically adapt to different healing stages, the coordination of multiple simultaneous response signals, and the achievement of an optimal balance between biosafety and therapeutic functionality. Future research directions may include organ-on-a-chip (OoC) platforms to simulate wound microenvironments, minimizing off-target effects in biomimetic systems, and creating multiscale frameworks for evaluating biocompatibility. A more integrated approach that combines mechanistic understanding, materials innovation and clinical validation is critical for the advancement of precision and personalized management of diabetic wounds.

2. Pathophysiology of Diabetic Wound Healing

2.1 Characteristics of diabetic wounds and their impact on each stage of wound healing

Diabetic wounds are defined by their chronicity and resistance to healing [1]. The pathophysiology behind this is chronic inflammation, poor angiogenesis and susceptibility to bacterial infection. The hyperglycemic microenvironment enhances excessive accumulation of ROS, which induces sustained expression of pro-inflammatory factors, thus continuing a vicious cycle of inflammation [4, 6]. Additionally, hyperglycemia causes damage to the vascular endothelial cells, resulting in impaired neovascularization and chronic local hypoxia in the wound [4]. Elevated glucose levels also support the growth of pathogenic bacteria, which greatly raises the risk of infection [10]. Moreover, peripheral neuropathy has been shown to interfere with the tissue repair process, further complicating wound healing in diabetic patients [19, 20].

Abnormally prolonged inflammatory phase: In normal wound healing, the inflammatory phase is normally short. However, in diabetic wounds this response is unable to resolve on time, as a result of macrophage dysfunction [21, 22]. Notably, the expression of netrin-1 protein is significantly reduced in diabetic wounds, which affects the polarization of macrophages into the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. Concurrently, pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 are continuously secreted and create a pathological inflammatory microenvironment [21, 23].

Impaired proliferative phase function: Persistent hyperglycemia has been demonstrated to suppress fibroblast activity, leading to decreased synthesis and disordered structure of the ECM [24]. Oxidative stress, which is associated with excessive production of ROS, further impair keratinocyte migration and slows epithelialization [25]. The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling pathway is inhibited, worsening the hypoxia in the tissues with the lack of blood vessel formation [26]. Moreover, impaired expression of pro-angiogenic factors such as Cu2+ and netrin-1 affects the proliferation of endothelial cells in diabetic wounds [27, 28].

Structural defects during remodeling: An imbalance in collagen cross-linking causes reduced scar strength [25]. The prolonged action of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) leads to the breakdown of newly formed tissue in excess, making wounds prone to recurrence or deterioration [29].

The diabetic wound microenvironment is defined by a complex interplay of pathological factors. Hypoxia and oxidative stress are reciprocally related: hypoxia leads to increased ROS generation, which further accumulates and suppresses the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), leading to a vicious cycle [30, 31]. Likewise, infection and inflammation act in a synergistic manner to increase tissue damage with bacterial biofilms enhancing the inflammatory response whereas proteases released by inflammatory cells degrade the antimicrobial barrier [5, 32].

Schematic representation of the pathological characteristics of diabetic wound healing and the types and classification criteria of the cascade reactions contained in microenvironment-responsive hydrogels. Created in BioRender. Jia, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/b8q7n94.

Conventional therapeutic modalities often have difficulty modulating these multifaceted factors simultaneously [33]. Recent advances have revealed novel strategies that target macrophage phenotype switching, for example, topical administration of exosomes (Exos) has been demonstrated to promote macrophage polarization towards the M2 phenotype [34]. In addition, the dual control of oxidative stress and angiogenesis by nano-enzymatic materials has proven to be promising [35]. Metal-organic framework (MOF)-based catalysts have shown the potential of scavenging ROS and facilitating vascular regeneration [36]. Furthermore, smart-responsive dressings, such as glucose-sensitive hydrogels allow dynamic drug release based on microenvironment changes in the wound [6, 10].

Given the multifactorial and interactive nature of diabetic wounds, pathological deviations occur in the various phases of the inflammatory, proliferative and remodeling phases of healing. Future studies should focus on the development of multi-target synergistic intervention strategies designed to restore and restructure the wound microenvironment in order to promote effective healing.

2.2 The important regulatory role of the immune microenvironment (macrophages, neutrophils) in each stage of diabetic wound repair

The skin immune microenvironment is a complex network of cells including neutrophils, macrophages, T cells, B cells and natural killer (NK) cells that interact closely with keratinocytes and fibroblasts to maintain tissue homeostasis and defend against pathogens [37-39]. These immune cells communicate mainly via cytokines, orchestrating processes that are important for wound healing. Neutrophils are responsible for clearing debris and pathogens, macrophages for guiding tissue repair by dynamic M1 to M2 polarization, and T cells for regulating adaptive immunity. Upon injury of the skin, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), a multifunctional cytokine implicated in the regulation of inflammation and tissue regeneration, is released by platelets to recruit neutrophils. Afterward, the macrophages change from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the reparative M2 phenotype, while fibroblasts participate in ECM reconstruction [39-41]. Macrophages release the growth factors, VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor, which play a key role in angiogenesis and epithelial regeneration.

In the case of diabetic wounds, this finely tuned repair program is broken. Hyperglycemia inhibits M2 macrophage polarization through ROS/NF- κB signaling axis, which sustains a predominance of the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and perpetuates chronic inflammation [42-45]. Additionally, the ECM altered by advanced glycation end products (AGEs) negatively affects healing by impairing TGF-β signaling, blocking fibroblast migration and reducing the response of endothelial cells to the growth factor VEG during the inflammatory phase. Emerging therapeutic approaches are aimed at "restarting" the impaired repair process. These include delivery of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 or TGF-β using nanocarriers to induce M2 macrophage activation, as well as modulation of ROS/NF- κB signaling pathways using MOFs. Tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6 (TSG-6), an anti-inflammatory glycoprotein released by mesenchymal stem cells, plays a very important role in immune balance restoration and ECM remodeling, acting as a key mediator in the use of stem cell-based therapies in the reshaping of the immune niche [44-50]. Functional hydrogels also play a role by relieving hypoxia and improving angiogenesis. Collectively, these strategies address the intertwined triad of inflammation, hypoxia, and infection that is the basis for impaired diabetic wound healing.

2.2.1 Inflammation phase

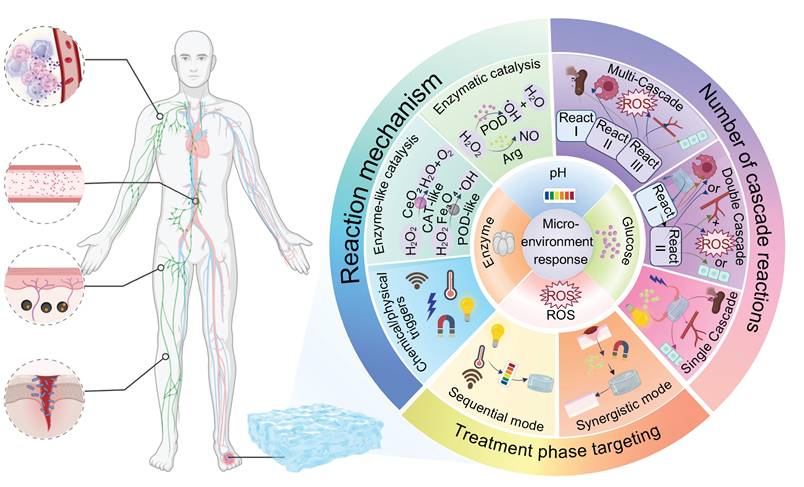

Hyperglycemia disrupts the skin barrier, promotes bacterial colonization, and increases inflammatory responses. Under high glucose conditions, mitochondrial dysfunction and activation of the enzyme NADPH oxidase cause increased ROS production, which causes damage to vascular endothelial cells and collagen, and inhibits macrophage polarization toward the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β [51-54]. This metabolic imbalance traps macrophages in the pro-inflammatory state called M1, and creates a vicious cycle of inflammation, oxidative stress, and infection. Diabetic wounds are associated with significant immune dysfunction, including a M1/M2 macrophage ratio more than three-fold higher than in healthy tissue, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-12, impaired angiogenesis, and excessive neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), DNA-protein complexes secreted by neutrophils that trap microbes but also contribute to persistent tissue damage [55-59]. Additionally, T cells and dendritic cells become skewed to pro-inflammatory phenotypes accompanied by decreases of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and Th2 cells as well as increases in chemokine expression that inhibit fibroblast and endothelial cell functions [60-62]. Targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at promoting M2 macrophage polarization, collagen synthesis and re-epithelization are showing considerable promise. Engineered hydrogels and nanomaterials carrying IL-4, IL-13 or small interfering RNA (siRNA), which induces sequence-specific gene silencing through RNA interference, have shown promise in the modulation of the wound immune microenvironment [63-65] (Figure 2). Future research should be aimed at understanding the complex interactions between immune and matrix cells in order to develop precision strategies for chronic wound repair.

2.2.2 Proliferation phase

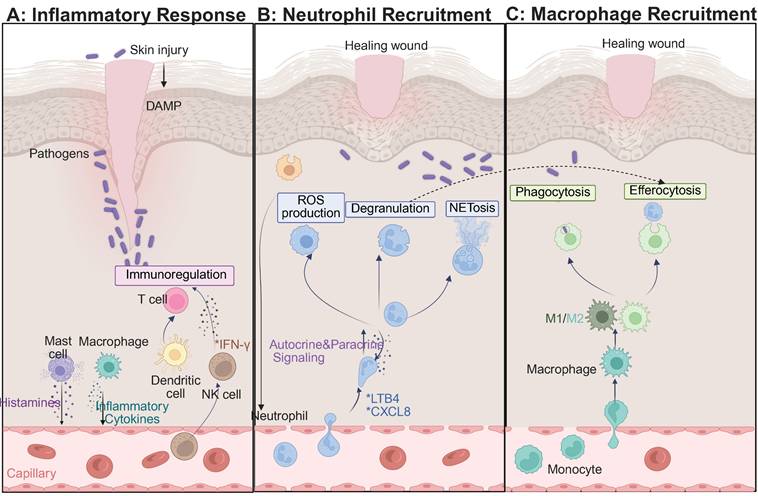

During the proliferative phase of diabetic wound healing, the regulation of the immune system is severely affected by hyperglycemia. Unlike the normal healing process, which promotes faster resolution by apoptosis of neutrophils and the activity of pro-resolving mediators, AGEs interact with their receptor (RAGE) in diabetic wounds, inhibiting macrophage autophagy by ~60%, which delays the important switch between the pro-inflammatory M1 and the reparative M2 phenotype [66, 67]. This impairment results in delayed clearance of cellular debris, increased ROS generation, impaired dendritic cell antigen presentation, and diminished phagocytic function of neutrophils and together leads to disruption of immune homeostasis. Normally, M2 macrophages make up some 70% of the immune cell population in wound tissue. However, there is an association between diabetes and a higher number of Treg cells and a reduced number of functional NK cells, which contribute to suppressed immune surveillance [68-70]. Pro-inflammatory Th17 and γδ T cells further increase the inflammation, and dendritic cells are unable to sufficiently support epidermal proliferation (Figure 3A). The polarization of M2 macrophages mediated by IL-4/IL-13-STAT6 signaling, adenosine-A2a receptor activation and miR-21-5p/PI3K-Akt pathway is suppressed under hyperglycemic conditions [71, 72]. Impaired clearance of NETs leads to oxidative stress "storms" that result in damage to the endothelium. Therapeutic interventions include IL-10 loaded hydrogels which have shown enhanced healing effects [73]. Toll-like receptor 7/8 agonists have been shown to induce M2 macrophage polarization, and peptidylarginine deaminase 4 inhibitors inhibit ROS accumulation. In addition, Sema4D-miR-21 scaffolds are also being investigated for their angiogenic potential [74]. Gene editing on RORγt and PD-1 pathways is a promising approach to precise immune modulation [75-77]. Ultimately, the translation of these findings into clinical practice requires a multifaceted approach to harmonize resolution and regeneration through spatiotemporal, multi-omics-based interventions.

Dynamic evolution of immune microenvironment in the inflammatory phase of diabetic wound healing (A: inflammatory; B: neutrophil recruitment; C: macrophage recruitment). Created in BioRender. Jia, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/lcu92wa.

(A) Dynamic evolution of immune microenvironment in the proliferative phase and (B) Reshaping phase of diabetic wound healing. Created in BioRender. Jia, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f8nmo43.

2.2.3 Reshaping phase

In the remodeling phase of diabetic wound healing, AGEs have been shown to destroy collagen cross-linking by covalent modification, leading to a reduction in tensile strength of more than 60% [11, 78]. Concurrently, the ratio of MMP-9 to its tissue inhibitor TIMP-1 changes dramatically to 5:1, favoring excessive and disorganized degradation of ECMs. Macrophage-derived lysyl oxidase (LOX), an extracellular enzyme important in the crosslinking of collagen and elastin, shows a 40% reduction in activity [79, 80]. The HIF-1α-mediated glycolytic pathway favors pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages over M2 phenotypes, disrupting fibroblast contraction through elevated IL-6 and TNF-α levels and inhibiting apoptosis of myofibroblasts [81]. Treatment with metformin, which acts through AMP-activated protein kinase, has been seen to restore M2 macrophage polarization by 50%, and normalizes LOX activity by 70%. Neutrophils have a significantly extended half-life, ~12-fold, and contribute to chronic NETosis and M2c macrophage polarization via histone H3 signaling. DNase I therapy has been shown to decrease the thickness of scars by 50% [82, 83]. Additionally, apoptosis of Tregs cells and IL-10 deficiency cause impairment in antifibrotic functions, while NK cells have a 50% impairment in their ability to clear senescent fibroblasts due to NKG2D glycosylation alterations [84-86]. The pathological basis of diabetic wound remodeling thus involves disruption of the AGEs-RAGE-MMP-9 axis, dysfunction in metabolism-mechanics signaling, and hypoxia marked by a 40% reduction in blood flow. Therapeutic interventions such as HIF-1α inhibitors, pH-responsive DNase I, and copper oxide (CuO)-loaded biomimetic scaffolds have shown promise, enhancing healing rates by twofold (Figure 3B) [87, 88]. Multiscale regulation of the interconnected “matrix-immunity-metabolism” triad is essential for reversing chronic fibrosis and promoting effective wound remodeling.

3. Types of Microenvironment-Responsive Hydrogels

Chronic diabetic wounds constitute a highly dynamic and pathologically complex microenvironment, often characterized by persistent hyperglycemia, chronic inflammation, excessive oxidative stress and abnormal MMP activity all of which severely impair tissue regeneration [89, 90]. Although conventional hydrogel dressings offer advantages such as moisture retention and physical protection, they are usually not able to actively sense and respond to pathological cues. As a result, they fail to meet the stage-specific and multi-target and changing needs in the management of a diabetic wound [25, 90-92]. In this regard, microenvironment-responsive hydrogels have become an advanced class of functional biomaterials that can sense pathological stimuli, such as glucose, pH, ROS, and MMPs, and then induce spatiotemporally controlled drug release and wound microenvironment modulation. By adding dynamic covalent bonds, enzyme sensitive peptide linkers or redox responsive moieties, these hydrogels exhibit smart responsiveness, which allows for simultaneous control of inflammation, stimulation of angiogenesis, and decrease of oxidative damage [93-100]. Based on their stimulus recognition mechanism, these systems are broadly categorized as glucose-responsive, pH-responsive, enzyme-responsive and ROS-responsive hydrogels [101-104]. The following sections systematically review their design principles, therapeutic mechanisms, and recent advancements in the remodeling of the diabetic wound microenvironment to give both theoretical insight and practical guidance for the development of next-generation multi-responsive platforms.

3.1 Glucose-responsive hydrogel

Chronic diabetic wounds are closely associated with the hyperglycemic microenvironment. Prolonged hyperglycemia not only provides a nutrient-rich substrate for bacterial proliferation, which increases the infection risk of pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by over threefold [105], but also persistently activates the M1 polarization of macrophages. This activation results in excessive release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6, TNF-α) and increased oxidative stress [106]. Additionally, deposition of AGEs inhibits the expression of VEGF, leading to tissue hypoxia and failure of vascular regeneration. Together these factors form a vicious cycle of hyperglycemia, infection, inflammation, and vascular damage [107].

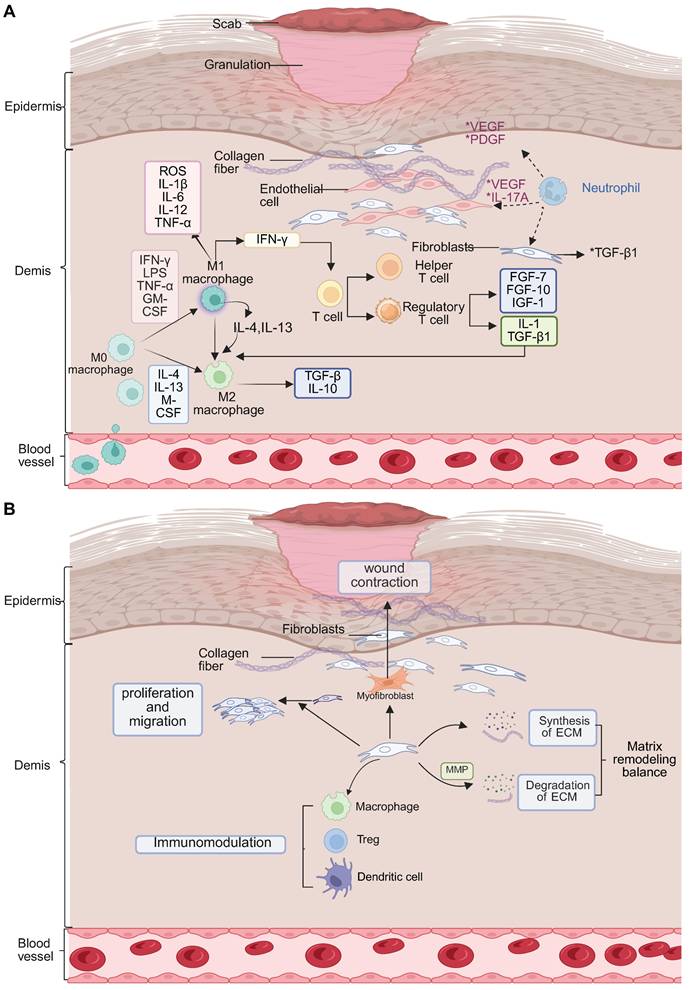

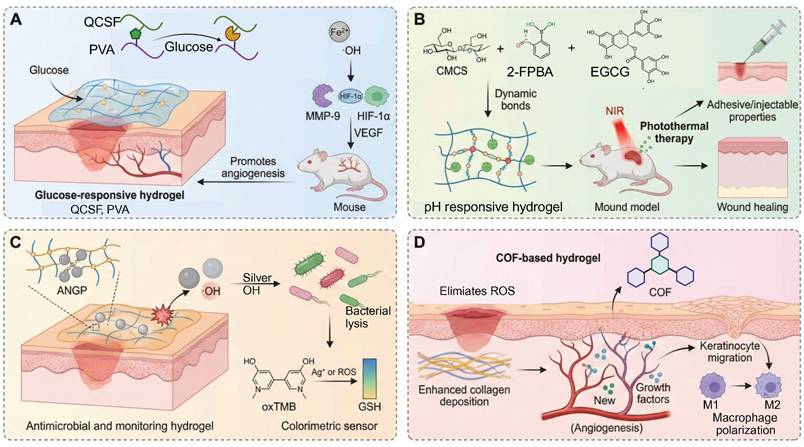

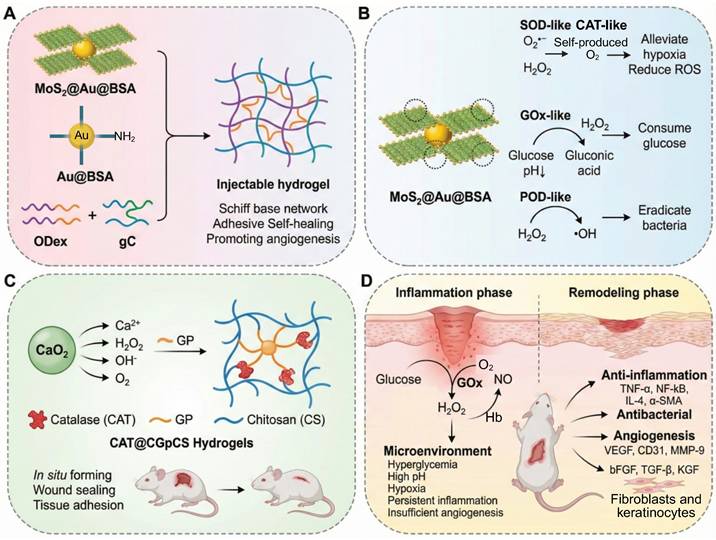

In order to break this harmful cycle, researchers have developed smart hydrogel systems based on multi-responsive mechanisms. Among these, catalytic systems driven by glucose oxidase (GOx) have shown excellent but condition-dependent performance. For example, a boronic ester-crosslinked hydrogel based on modified quaternized chitosan and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), which reacts with high glucose levels and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), breaks dynamic boronic ester bonds, thus reducing oxidative stress and releasing deferoxamine-loaded gelatin microspheres (DFO@G). The activation level for this glucose triggered reaction (≈15 mM) is very close to the pathological blood glucose range found in diabetic wounds (10-25 mM), ensuring physiological relevance. Subsequently, MMPs promote the long-term release of DFO, which promotes the expression of HIF-1α and angiogenesis, promoting the healing of diabetic wounds (Figure 4A) [101]. More innovative self-regulating systems, such as MN-GOx/Arg microneedles, are responsive to MMP-9 overexpression in the wound microenvironment and trigger arginine release via cascade reactions. This facilitates collagen deposition and angiogenesis which enhances the wound healing rate in diabetic rats by 2.3 times [108, 109]. Similarly, Li et al. developed a quaternized chitosan/salvianolic acid B (QF/SAB) hydrogel with dynamic boronic ester and imine bonds, which are sensitive to both glucose and ROS. This allows on-demand drug release, ROS scavenging, and improved angiogenesis with more than 90% wound closure in diabetic models [110]. A triple-responsive hydrogel that quickly releases insulin in the acidic (pH 5.5-6.5) and high temperature (40-42 °C) environments characteristic of wound surfaces through the synergistic effect of the Schiff base, boronic acid ester and hydrogen bond interactions. In addition, it has a photothermal antibacterial effect and inhibits over 95% of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) under near-infrared (NIR) irradiation [111]. Photoresponsive hydrogels are a new method of deep-tissue repair. For example, a Rh/AgMoO nanozyme composite hydrogel produces ROS (•OH and O₂⁻) and hydrogen under visible light excitation. This process inhibits bacterial glycolysis by disrupting the phosphotransferase system and downregulates the expression of the RAGE improving the wound healing rate of diabetic mice by 78% [112]. Experiments have demonstrated that such hydrogels can simultaneously control macrophage M2 polarization and promote angiogenesis to achieve multidimensional microenvironmental repair. Comparative studies have shown that glucose responsive systems are more specific for their substrates than pH or ROS responsive hydrogels, but are more sensitive to variations in oxygen concentration and enzyme stability. Despite these promising results, the clinical translation of glucose-responsive hydrogels is faced with several challenges. The stability and catalytic efficiency of GOx are affected by variations in pH and local hypoxia conditions, which results in inconsistent performance in vivo. Moreover, the overaccumulative byproduct of the oxidation of glucose, H2O2, may cause oxidative stress and tissue irritation. Future studies should be designed to combine biomimetic enzyme mimics and oxygen-controlled cascade systems to enhance long-term catalytic efficiency, biosafety, and clinical reliability.

Types of microenvironmental responsive hydrogel. (A) Glucose-responsive hydrogel. (B) pH-responsive hydrogel. (C) Enzyme-responsive hydrogel. (D) ROS-responsive hydrogel. Created in BioRender. Jia, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/4spcrm7.

3.2 pH-responsive hydrogels

The pH of diabetic wounds is not static but changes dynamically throughout the healing process. The wound environment during the inflammatory stage is generally mildly alkaline, which is thought to be due to chronic exudation and increased protease activity [113]. As infection progresses, the metabolism of bacteria and tissue necrosis lead to the accumulation of lactic and fatty acids, which creates a microenvironment that is more acidic [114]. These dynamic pH changes represent the pathological changes that occur at various stages of healing in chronic, non-healing diabetic wounds, underscoring the complex interplay between inflammation, tissue necrosis and bacterial colonization [115]. Accordingly, the design of pH-responsive hydrogels that can adapt to these fluctuations is crucial in order to ensure efficient drug delivery during the healing process. Such responsiveness is mainly accomplished by reversible ionization and or dynamic covalent bonding mechanisms that are sensitive to pH variations.

In material design, natural polysaccharides like chitosan and gelatin are commonly used because of their good biocompatibility and cell proliferation. For example, modified gelatin/chitosan composite systems significantly increase the pH responsiveness and antibacterial activity under laboratory conditions due to dopamine coating and quaternization treatments [116]. On the other hand, synthetic polymers such as PVA and polyacrylic acid (PAA) are frequently used. PVA/CS-BA systems that are formed by dynamic covalent cross-linking, e.g., borate and hydrogen bonds, can intelligently release pro-angiogenic drugs in response to the acidic environment induced by infection and metabolic byproducts such as lactic acid, while retaining a moist wound environment [117]. This pH-triggered drug release, which is effective in a pH range of 5.5 to 7.0, is quite compatible with the pH variations that typically occur in diabetic wounds (pH 5.4-8.9), thus highlighting its physiological relevance [118]. Recent studies highlight that the pH-dependent assembly or disassembly of the phytochemical-based hydrogels based on tannic acid, gallic acid, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) occurs via hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking. This allows acidity induced softening and accelerated release of intrinsic bioactive components without need for additional carriers [119]. Notably, a recently developed EGCG-based adhesive hydrogel based on carboxymethyl chitosan and 2-formylphenylboronic acid via dual dynamic covalent bonds with favorable mechanical strength, antioxidant capacity, and pH-controlled EGCG release. This design also provides on-demand dissolvability to reduce secondary damage during dressing removal (Figure 4B) [102].

Furthermore, multi-component composite hydrogels incorporating PAA and natural cellulose along with modified carbon quantum dots, exhibit both self-healing properties and real-time pH monitoring [120]. When wound pH is reduced from 7.4 to 5.8 by bacterial infection, carbon quantum dots induce controlled drug release, and antimicrobial peptides release rate is 3.8-fold higher. Simultaneously, the addition of zinc oxide nanoparticles results in improved mechanical properties (compressive strength up to 45 kPa) as well as antioxidant efficiency (the 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical scavenging rate is more than 90%). This pH-responsive and graded release mechanism not only enhances insulin release in acidic conditions (4.2-fold increase in release rate) but also burst release of antimicrobial drugs in alkaline conditions, which reduces inflammatory factors and enhances the process of angiogenesis. Moreover, phytochemical alkaloids such as berberine and flavonoids such as curcumin show increased solubility and intermolecular mobility in mildly acidic microenvironments, which allows self-controlled release kinetics to complement conventional polymeric pH-responsive platforms.

In summary, pH-responsive hydrogels, with their ability to perform precise drug delivery, intelligent monitoring, and multifunctional integration, are a versatile platform for the management of diabetic wounds. However, the dynamic pH range in chronic wounds is relatively small and spatially heterogeneous, which often restricts the full activation of these systems. Localized infection and necrosis can create conflicting micro-pH gradients and buffering capacity of the wound exudate may further reduce responsiveness. Compared to glucose or enzyme responsive systems, pH responsive hydrogels provide a faster but less specific regulatory response. These limitations indicate that future designs should combine pH sensitivity and biochemical recognition mechanisms to provide more precise and sustained therapeutic control.

3.3 Enzyme-responsive hydrogels

In human tissues, enzymes are ubiquitous natural biocatalysts. Their high specificity and rapid response enable them to be known to play key roles in ECM remodeling, cell migration, and signal transduction [29, 121]. During normal wound healing, enzymes participate in inflammation regulation, angiogenesis, and collagen deposition, thereby promoting tissue regeneration. However, due to persistent hyperglycemia and oxidative stress, the local microenvironment of diabetic wounds is significantly disturbed, accompanied by chronic inflammation and abnormally elevated MMPs and cyclooxygenase-2 activities[122]. These abnormal enzymes not only disrupt the normal secretion of growth factors such as VEGF and EGF, but also inhibit the formation of granulation tissue by excessively degrading ECM components such as collagen, ultimately leading to stagnation of wound repair. In addition, iron ion overload and ROS accumulation further aggravate tissue damage forming a vicious cycle [123].

Enzyme-responsive hydrogels have a three-dimensional network structure similar to that of ECM, and are self-repairing and highly permeable, and can dynamically respond to the complex microenvironment of diabetic wounds [31, 108, 124]. A POD-mimetic lysozyme-hemin nanozyme-anchored Gelatin/PVA hydrogel (ANGP) exploits bacterial GSH-mediated catalysis for rapid colorimetric detection and •OH-based sterilization, though long-term hemin release remains to be optimized (Figure 4C) [103]. Compared with traditional dressings that passively release drugs, this type of hydrogel responds to abnormal enzyme activity through dynamic covalent bonds (such as phenylboronic acid ester bonds) or breakable connections composed of MMP-sensitive peptides, thereby achieving precise on-demand release of drugs and regulation of the microenvironment [125]. For example, in wound areas where MMP-9 is overexpressed, hydrogels can simultaneously release anti-inflammatory drugs or iron chelators after enzymatic degradation, maintaining the structural stability of the ECM while exerting anti-inflammatory and oxidative stress-reducing effects [126]. This dual function gives it significant advantages in scavenging ROS, inhibiting inflammation, and promoting angiogenesis.

In response to the challenges of MMP overexpression and iron ion imbalance in diabetic wounds, researchers designed a composite hydrogel system based on modified alginate and polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA). This system introduces MMP-sensitive peptides as crosslinkers and loads microspheres containing the iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO) to achieve a dual response to abnormal enzyme activity and iron ion overload [126]. In an acidic environment or in areas with high MMP expression, the hydrogel releases DFO through enzymatic degradation, effectively chelating free iron, reducing ROS levels, improving the microenvironment, and promoting vascular endothelial cell migration. Animal experiments have shown that this system was reported to increase the expression of VEGF and CD31 and to promote collagen deposition and granulation tissue formation, and thus shortens the healing cycle.

In order to overcome the problems of low drug release efficiency and insufficient biological activity of traditional hydrogels, researchers further integrated mesenchymal stem cell-derived Exos (MSC-exos) into enzyme-responsive hydrogels. For example, the "MSC-exo@MMP-PEGDA" hydrogel embeds Exos into the MMP-sensitive cross-linking network through electrostatic adsorption [127, 128]. In the area where MMP-9 is highly expressed, the hydrogel gradually degrades and continuously releases Exos. Exos can activate the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway to promote endothelial cell proliferation, while inhibiting NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response. The miRNAs they carry can also regulate ECM synthesis-related genes, reduce excessive collagen deposition and inhibit scar formation. This composite system showed a sustained release effect of up to four weeks in a diabetic rat model, significantly improving re-epithelialization and angiogenesis.

In summary, enzyme-responsive hydrogels have unique merits in the controlled drug release and adaptive microenvironment regulation via biologically specific degradation [108, 129]. However, their performance remains highly dependent on the fluctuating enzyme activities present in chronic diabetic wounds, which can result in inconsistent release profiles. The synthesis of enzyme-cleavable linkers and incorporation of bioactive cargos also increase manufacturing complexity and limit large-scale production. Compared with pH- or ROS-responsive systems, enzyme-responsive hydrogels exhibit superior specificity but slower response kinetics and reduced structural stability [12, 113, 130]. Therefore, future research should focus on designing hybrid hydrogels that integrate enzyme-responsive degradation with other stimuli-sensing elements to enhance precision and translational feasibility.

3.4 ROS-responsive hydrogel

ROS are a class of highly oxidative molecules, including O2-, H₂O₂ and ·OH, which are inevitable byproducts of cellular metabolism. Diabetic wounds fall into a vicious cycle of "difficult to heal-infected-necrotic" due to the imbalance of oxidative stress caused by persistent hyperglycemia. ROS have a biphasic regulatory effect in wound repair. At physiological concentrations, ROS promote angiogenesis by activating the VEGF signaling pathway and drive the bactericidal function of neutrophils [131]. However, in the diabetic wound microenvironment, abnormal mitochondrial electron transport chain leads to a surge in ROS (>100 μM H₂O₂), breaking through the redox homeostasis threshold, triggering overactivation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, prompting macrophages to polarize to the pro-inflammatory M1 type, inhibiting collagen deposition and exacerbating ECM degradation [25, 132]. Studies have shown that ROS levels in diabetic wounds are 3-5 times higher than those in normal tissues, forming a positive feedback loop with pro-inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and IL-6, further aggravating hypoxia and vascular regeneration disorders [133]. Although traditional hydrogel dressings can provide a physical barrier and local moisturizing, they lack dynamic response capabilities: single antioxidant components (such as vitamin C) are easily exhausted in the early stage and cannot cope with continuous ROS generation; the separation of antibacterial and healing functions leads to insufficient control of deep tissue infection, and the hypoxic microenvironment hinders late epithelial regeneration [134]. For example, although ordinary chitosan hydrogels have antibacterial properties, they cannot target the removal of intracellular ROS or regulate macrophage phenotypic transformation [135].

In view of the limitations of traditional materials, smart responsive hydrogels have attracted increasing attention due to their dynamic molecular design and technological integration. Among them, the “ROS threshold trigger” mechanism based on dynamic covalent bonds has emerged as a key approach: the thioketone bond (-SS-) and the phenylboronic acid bond are selectively broken under pathological ROS levels(Among them, the -SS- and the phenylboronic acid bond are selectively broken under pathological ROS levels (typically ≈100 μM H₂O₂, within the physiological ROS range of 50-200 μM in diabetic wounds)) to achieve spatiotemporal controllable drug release. For example, CMCS-PBA/OXD hydrogel preferentially releases α-lipoic acid in the high ROS area of the wound through ROS-sensitive Schiff base bonds to modulate ROS levels and inhibit biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus [12]. In addition to the ROS responsive dynamic linkages commonly used in synthetic hydrogels, several traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) derived phytochemicals such as baicalein, quercetin, and resveratrol have been reported to undergo ROS mediated oxidation or structural softening [136-142]. This behavior increases molecular mobility and promotes the release of their intrinsic antioxidant components. These TCM related antioxidant frameworks thus offer a biodegradable and biocompatible supplementary mechanism for ROS responsive modulation in chronic diabetic wounds, while avoiding the long term biosafety issues associated with metal based catalytic systems. For the improvement of the hypoxic microenvironment, the bionic cascade strategy of oxygen self-supply and antioxidant system shows significant advantages. For instance, a dynamic oxygen-releasing hydrogel constructed by encapsulating basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), microalgae, and COF-1 into a self-assembled network demonstrates synergistic effects in alleviating oxidative stress and promoting angiogenesis. The borate-based covalent organic framework (COF) achieves ROS scavenging and glucose-responsive degradation, while the microalgae continuously provide the dissolved oxygen to alleviate the hypoxia. In addition, the B-N coordination bonds assist in pH-sensitive drug release. This multifunctional hydrogel has a favorable biocompatibility and can promote re-epithelization and collagen remodeling in diabetic wounds, which is a promising strategy for wound management in chronic wounds (Figure 4D) [104].

In summary, ROS-responsive hydrogels can effectively modulate oxidative stress, angiogenesis enhancement, and immune remodeling via threshold-triggered and cascade catalytic mechanisms. However, the concentration and distribution of ROS in chronic wounds is highly variable and this makes precise activation control difficult. Excessive scavenging of ROS may impair normal redox signaling, whereas insufficient response could fail to alleviate oxidative damage. In addition, the long-term biosafety of metal-based nanozymes and quantum dots remains uncertain, and their mechanical stability is often inadequate for deep wound support. Compared with enzyme- or glucose-responsive systems, ROS-responsive hydrogels provide faster responses but lower selectivity and reduced structural integrity. Therefore, future research should aim to establish quantitative redox regulation and develop biodegradable, metal-free catalytic systems to achieve safe, tunable, and clinically reliable wound therapies.

To provide a concise summary of the single-stimulus systems discussed above, Table 1 compiles representative examples of glucose-, pH-, enzyme-, and ROS-responsive hydrogels reported in 2024-2025, along with their key physical parameters. This comparative overview highlights how each stimulus type influences the mechanical, adhesive, and degradation behaviors of the hydrogels, offering a foundation for the development of multi-responsive platforms discussed in the next section.

Representative single-stimulus microenvironment-responsive hydrogels for diabetic wound healing and their key physical properties (2024-2025). All values represent typical ranges reported in the cited literature, and may vary substantially depending on formulation composition and testing conditions.

| Hydrogel type | Representative system | Core mechanism | Compressive strength (kPa) | Adhesive strength (N cm⁻²) | Swelling Ratio (%) | Degradation rate (% mass loss, days) | Ref. (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose-responsive | Zn-MOF-GOx cascade nanoreactor | GOx-catalyzed glucose oxidation triggers NO generation and microenvironment modulation | 65 ± 5 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 370 ± 25 | 45 ± 3 (7 d) | [101] (2024) |

| Glucose-responsive | Multienzyme “nanoflower” hydrogel (GOx-activated NO) | Glucose-triggered NO release from multienzyme composite | 72 ± 6 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 380 ± 20 | 50 ± 4 (7 d) | [109] (2025) |

| pH-responsive | TA/QCMC/OSA injectable hydrogel | Acid-base reversible dynamic bonds enabling pH-triggered release | 60 ± 4 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 350 ± 15 | 40 ± 5 (5 d) | [102] (2024) |

| pH-responsive | Acid-responsive CST@NPs system | Acidic wound milieu triggers drug release from acid-labile construct | 45 ± 3 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 390 ± 30 | 42 ± 6 (7 d) | [116] (2024) |

| Enzyme-responsive | MMP-9-responsive hydrogel (ferroptosis suppression) | MMP-cleavable crosslinks enable on-demand release; protects endothelial cells from ferroptosis | 70 ± 5 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 380 ± 25 | 55 ± 4 (10 d) | [126] (2024) |

| Enzyme-responsive | MMP-9-responsive exosome-releasing hydrogel | MMP-sensitive network degrades to release MSC-derived exosomes | 68 ± 5 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 370 ± 20 | 50 ± 5 (10 d) | [127] (2025) |

| ROS-responsive | HA-based ROS-responsive injectable hydrogel (HA@Cur@Ag) | ROS-cleavable/disulfide chemistry enables on-demand release and ROS scavenging | 68 ± 6 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 400 ± 30 | 45 ± 5 (7 d) | [12] (2024) |

| ROS-responsive | GelMA/PVA-UIO-66-NH₂@Quercetin nanocomposite hydrogel | MOF-assisted ROS-responsive release; modulation of inflammatory microenvironment | 75 ± 7 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 390 ± 20 | 48 ± 4 (10 d) | [104] (2025) |

As summarized in Table 1, single-stimulus microenvironment-responsive hydrogels show different physical behaviors mainly due to the differences in their molecular crosslinking mechanisms. Glucose- and enzyme-responsive systems typically employ covalent or enzyme cleavable linkages that yield denser polymer networks, providing higher mechanical strength and slower and more controlled rates of degradation. In contrast, pH- and ROS-responsive hydrogels are typically formed by reversible dynamic bonds, such as imine, borate, or disulfide bonds, that are easily cleaved under acidic or oxidative conditions. These structural characteristics encourage higher network relaxation, swelling ratios, and faster disassembly, which aids in on-demand release of drugs.

Overall, these distinctions emphasize the specific benefits and drawbacks of each stimulus type in striking the right balance between stability and responsiveness. Such insights offer a structural basis for the design of multi-responsive hydrogels with complementary properties, which will be discussed in the next section.

3.6 Multi-responsive hydrogels

Diabetic wounds are defined by a vicious cycle, including hyperglycemic microenvironment, constant oxidative stress (ROS), overexpression of MMP-9 and the imbalance of inflammatory mediators (especially the IL-10/TNF-α ratio). This complex and dynamically intertwined pathology poses great challenges to conventional single-responsive hydrogels. For instance, strategy that is focused only on scavenging ROS may result in excessive ROS depletion, impairing their physiological pro-angiogenic functions. Similarly, a hydrogel that can only respond to pH changes has difficulty responding to the multi-stage requirements of diabetic wounds, which include anti-infection, anti-inflammation, and tissue regeneration [148]. In this context, multi-stimulus responsive systems are on the verge of integrating signals of glucose, ROS, pH, enzymatic activity and temperature to achieve temporally and spatially adaptive, precisely synergistic therapeutic effects. During the first inflammatory phase, a dual pH/ROS-responsive module can release antimicrobial agents to inhibit infection (Figure 5A) [143]. In the following phase, the regulation of redox balance and immune microenvironment is accomplished by the action of enzymes or temperature-sensitive mechanisms. Finally, in the remodeling phase, the sensitivity of glucose may be used to stimulate angiogenesis and the ECM remodeling process to aid in the entire wound healing process [121]. This development of dynamic sensing and multi-modal responsiveness highlights the potential of multi-responsive hydrogels as a transformative technology to overcome the persistent challenges in diabetic wound healing.

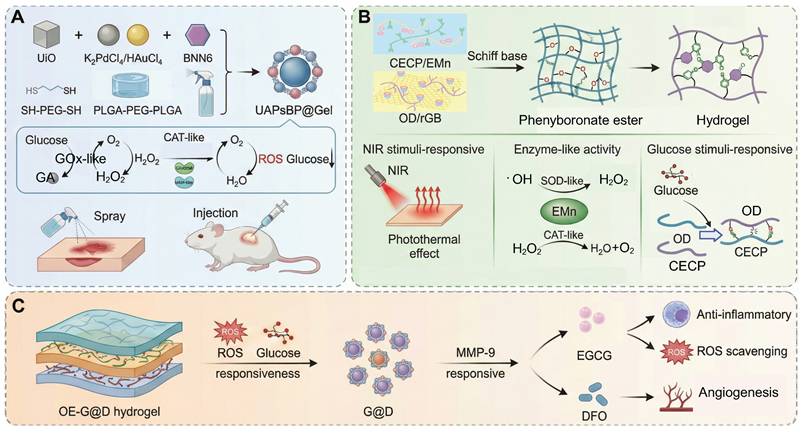

To meet the complex requirements in diabetic wound treatment, a hierarchical and progressive design paradigm has been proposed by researchers [144-151]. For instance, a COF-modified microalgae hydrogel system was created that combines glucose, ROS and NIR light responsiveness in one therapeutic system [144]. The boronic ester-based COF-1 scavenges ROS and allows glucose-triggered release of bFGF and embedded microalgae continuously generate oxygen to relieve hypoxia (Figure 5B). Upon 808 nm NIR irradiation, localized heating promotes the permeability of the gel and increases the speed of cargo release. This synergistic system enhances angiogenesis, inhibits inflammation and restores redox balance, which greatly enhances diabetic wound closure and tissue regeneration through a cascade-responsive mechanism. The combination of boronic ester-linked COFs and microalgae enables glucose- and ROS-responsive drug release, and NIR-induced oxygenation. This spatiotemporal synergy counteracts oxidative damage caused by hyperglycemia and re-establishes redox homeostasis, promoting angiogenesis, improving cell proliferation and accelerating chronic diabetic wound repair without interfering with physiological ROS signaling. Another innovative approach is through the adaptation of the healing process through a chronological sequential release strategy (Figure 5C). For example, a glucose/ROS/MMP-9 multi-responsive hydrogel (OE-G@D system) is sensitive to hyperglycemia in the early stage of inflammation by breaking phenylboronate bonds to release EGCG, which scavenges ROS and inhibits the accumulation of AGEs. This is followed by MMP-9-mediated release of DFO to stimulate angiogenesis [145]. During the repair phase, dissolution of a polysaccharide called chitosan under acidic conditions releases manganese-based nano-enzymes, which improves ROS scavenging efficiency and the rate of collagen deposition is increased by 50%. Cutting edge research is also being conducted on adaptive closed-loop systems, such as a dual-responsive electric field/temperature dressing that activates precise insulin delivery via a polyaniline conductive network that senses changes in wound potential (with sensitivity of 0.1 mV/mm2). This system integrates coupling temperature-sensitive polymer segments to mediate controlled release of VEGF, in addition to real-time biomarker monitoring using flexible microelectrodes, to create a dynamic "sense-respond-regulate" closed-loop treatment platform [147].

Types of multi-responsive hydrogel. (A) pH/ROS responsive hydrogel. (B) NIR/Glu/ROS responsive hydrogel. (C) ROS/Glu/MMP responsive hydrogel. Created in BioRender. Jia, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f9fv3g2.

Despite the great progress, clinical translation of multi-stimulus-responsive hydrogels is still hindered by three key challenges: (1) material incompatibility, e.g. the tendency of uncontrolled cross-linking between ROS-sensitive thioether bonds and enzyme-sensitive peptide chains [148, 149]; (2) poor dynamic adaptability, i.e. delayed response to rapid pH fluctuation or pulsed bursts of ROS [150]; and (3) heterogeneity in large-scale production, such as AuNRs/chitosan complexes, which are suffering from batch-to-batch variability due to nanoparticle aggregation [151]. Specifically, chitosan-based complexes are prone to inconsistencies due to clustering of nanoparticles which affects reproducibility. To overcome these obstacles, future research is increasingly focusing on interdisciplinary and synergistic innovations. These include programming biomimetic topologies using DNA origami technology to build smart materials that can dynamically respond to multiple biomarkers such as MMP-9, IL-6 and VEGF; using genetically engineered cyanobacteria implanted into wounds to achieve simultaneous photosynthetic oxygenation and necrotic tissue degradation; and developing 3D-printed gradient drug-release hydrogels that incorporate macrogenomic data of the patients microbiota for personalized microbial modulation [152-155].

4. Designation of Cascade Reaction in the Responsive Hydrogels Combine with Treatment of Diabetic Wounds

Diabetic wound healing is a complex pathophysiological network, where the main difficulty of wound healing is caused by the spatiotemporal interaction of several pathological factors, such as bursts of ROS, protease imbalances, chronic inflammation, and impaired vascular regeneration in a hyperglycemic microenvironment. Traditional single target therapies have difficulty interrupting this multidimensional vicious cycle because of limited targets and mismatched therapeutic time windows. In recent years, cascade reaction strategies have been able to achieve temporal adaptation of multi-target synergistic intervention and therapeutic effects through the use of a trigger-response-amplification regulatory logic. Smart responsive hydrogels are suitable carriers for these strategies, allowing controlled delivery of cascade signals induced by pathological microenvironmental cues (such as pH, ROS levels or enzyme activity) to reshape the regenerative microenvironment in both spatial and temporal dimensions [12, 155]. Building on this concept, combined therapies not only improve the accuracy of the treatment, but also increase the biological effect of cascade reactions. Examples include the ability to simultaneously control angiogenesis and anti-inflammatory response through cascade release of nitric oxide (NO), or the use of cascade enzymatic reactions to selectively target and destroy excessive inflammatory mediators [19]. To systematically explore these mechanisms, this study uses a three-tier classification system according to reaction chain length, molecular mechanism, and treatment stage targeting to give a comprehensive analysis of the adaptation logic and translational potential of cascade reaction strategies for diabetic wound therapy [156].

4.1 Classification based on the number of cascade reactions

Given the complex pathological characteristics of diabetic wounds, including persistence of hyperglycemic microenvironment, drug-resistant bacterial infections, oxidative stress and inflammatory storms, traditional monotherapies often struggle to achieve effective dynamic intervention. In recent years, cascade-based stimulus-responsive hydrogel systems have become a cutting-edge approach to address these multifaceted challenges by a hierarchical and progressive treatment logic.

To gain a better understanding from a conceptual point of view, we use a more rigorous definition of a true cascade reaction: one in which the intermediate or product formed at one step directly drives or catalyzes the next step, leading to a self-propagating or sequentially amplified reaction. By contrast, systems which are triggered by a single stimulus are categorized as single-stimulus-responsive systems and do not, strictly speaking, constitute cascade reactions.

Accordingly, the systems reviewed in this section are classified according to the number of cascade levels, i.e. single-stimulus responsive systems, dual-layer cascades, and multi-layer cascade systems (Table 2). This classification reflects the different levels of coupling of reactions and functional complexity. It is important to emphasize that this framework is conceptual rather than a strict chemical-step definition and is used to clearly distinguish between simple stimulus-response systems and true multistep cascades while retaining internal consistency in the current discussion.

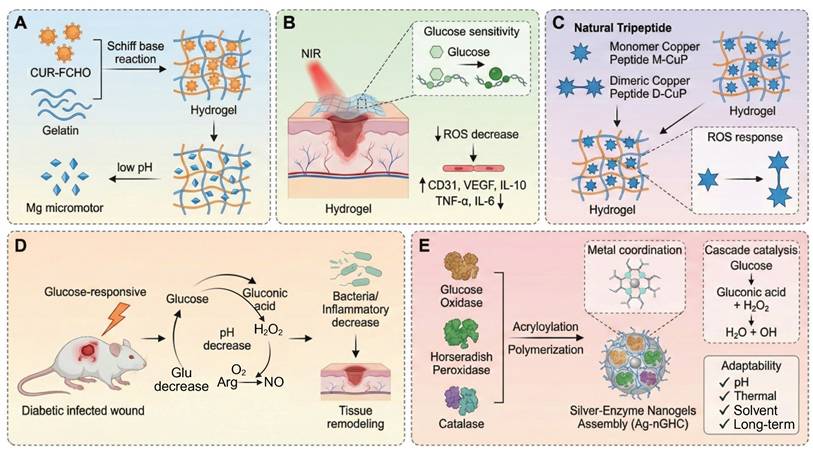

4.1.1 Single-stimulus responsive system

During the acute infection phase of diabetic wounds (within 48 hours), rapid acidification of the local microenvironment (pH=5.5 - 6.5) and the formation of biofilms by drug-resistant bacteria such as MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa represent the main threats [179]. In these scenarios, single stimulus responsive systems, which work through a single signal trigger mechanism, are often preferred because they are fast acting. Although these systems are not true cascade reactions, they are fast, targeted responses. For example, hyaluronic acid-based pH-responsive silver gel (HA-Ag) releases Ag+ ions via Schiff base bond cleavage in the acidic microenvironment with a peak concentration of 2.8 µg/mL in 24 hours and clears 99.3% of MRSA. However, residual Ag+ suppresses the migration of fibroblasts and retards the regeneration of the epidermis [180]. Similarly, the Gel-FCHO/Mg-motor GCM hydrogel decomposes the Schiff bases at wound pH 5.5-6.5, while releasing curcumin-containing micelles and H₂ produced by Mg micromotors. Yet, rapid Mg corrosion threatens to cause an alkaline shift (pH > 8), which results in loss of peptide stability and requires buffering of microdomains to keep local pH (Figure 6A) [157]. Another interesting design, a thermosensitive chitosan-tobramycin gel, induces a hydrophobic-hydrophilic transition at body temperature, which slowly releases tobramycin that penetrates biofilms with a 92% clearance rate and decreases local glucose concentration by 19% [181]. The major benefits of these single-stimulus systems are their ease of synthesis and speed of response, which make them especially useful in the outpatient setting for acute treatment of superficial ulcers. However, their linear release kinetics can lead to sudden release of the drug, which could potentially cause local oxidative stress, and they cannot control the release of inflammatory factors, which limits their efficacy in chronic wounds. As a complementary strategy, the PEG-DA/HA-PBA/MY hydrogel takes advantage of the glucose-induced borate cleavage to release myricetin selectively under hyperglycemic conditions (≥15 mM) to reduce ROS without stopping physiological H2O2 bursts. Nevertheless, its release drops dramatically below 8mM glucose, requiring secondary triggers during normoglycemic phases (Figure 6B) [158]. Meanwhile, the G/D-CuP hydrogel is based on dimeric CuP connected through ROS-cleavable bonds, where CuP is released only when H2O2 concentration is over 100 µM, hence coupling the anti-inflammatory and angiogenic effects. Dimerization provides increased protease resistance but can inhibit rapid diffusion in deep wound fissures (Figure 6C) [92]. Other single-layer systems have been based on thermal or enzyme-mediated cascade activation, e.g. temperature-triggered release of antibiotics, which maintains ROS production and wound closure [181, 182]. Compared to multilayer designs, these single-stimulus systems have simpler synthesis and quicker responses, and therefore are well-suited for early infection control. However, their linear release profiles and single level of activation limit their capacity to control inflammation and tissue regeneration over the long-term. Therefore, future research should be focused on the incorporation of secondary triggers or self-feedback mechanisms to increase the temporal adaptability and therapeutic precision of single-stimulus responsive systems.

Various types of cascade reaction-based stimuli-responsive hydrogels for promoting efficient repair of diabetic wounds and their therapeutic effects on wound healing.

| Classification | Hydrogel dressing | Triggers | Reaction unit | Therapeutic properties | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| single-stimulus responsive system | GMPE hydrogel | Glu | •Boronic ester bonds | • ROS scavenging • Inhibition of inflammation • Angiogenesis stimulation | [161] |

| HMPC hydrogel | Glu | •Boronic ester bonds | • Scavenges excessive ROS • Enhances angiogenesis | [162] | |

| TA/QCMCS/OSA@CQD hydrogel | pH | • Schiff-base bonds | •Anti-inflammatory activity•Antibacterial•Enhanced angiogenesis | [163] | |

| CF Gel @ Ber-F127 micelles | ROS | • CD-Fc host-guest interaction | •Anti-inflammator •Promotes M2 polarization | [24] | |

| HA-Gel hydrogel | MMP-9 | • MMP-9 cleaves gelatin network | •ROS scavenging •Promotion of angiogenesis •MMP-9-responsive controlled release | [164] | |

| LIN@PG@PDA hydrogel | Near-infrared light (NIR) | •NIR triggers photothermal effect via PDA •PNIPAM undergoes thermal-induced volume shrinkage | •Promotion of angiogenesis •Acceleration of epithelial regeneration •Enhanced wound closure | [165] | |

| NNH patch | Heat | •PNIPAM responds to heat •Inverse opal structure | • Promotion of angiogenesis • Collagen remodeling and epithelial regeneration | [166] | |

| Dual Cascade System | Gel(CaO₂/alg/Gox/Glu/NB/CAT-Ce₆) | Glu 660 nm laser | • Gox• CAT | •Antibacterial •Analgesic •Oxygen Supply •Enhance Photodynamic Therapy •Reduce Inflammation | [167] |

| BGL-interactive dynamic hydrogel | Glu pH | • Gox • Schiff-base bonds | •Maintain homeostasis •Promote wound healing •Antibacterial •Prevent continuous decline of BGL and pH •Adaptive behavior | [168] | |

| PBA/Cs hydrogel | Glu ROS | •Boronate ester bonds formed by PBA and diol-rich polymers | •Enhanced epidermal and dermal reconstruction •Promotion of angiogenesis | [169] | |

| Bi/Bi₂WO₆/H-TiO₂-gel | Visible light Glu | •Photocatalytic Z-scheme heterojunction • Glucose | •Continuous H2 generation •ROS scavenging and macrophage M1→M2 polarization •Inhibition of advanced AGEs •Promotion of angiogenesis, collagen remodeling, and cell proliferation | [170] | |

| EGC Hydrogel (LYZ-GOx-CAT) | Glu pH | •GOx:•Schiff base imine bonds | • Self-healing and shape adaptability • Glucose and ROS regulation • Promotion of angiogenesis and tissue repair • pH-responsive controlled release | [171] | |

| Multilayer cascade reaction system | GDHPC hydrogel | pH Glu ROS | •Borate ester bonds •Schiff base bonds | •Antioxidant •Anti-inflammatory •Antibacterial •Pro-angiogenic | [11] |

| PLPT hydrogel | Glu pH NIR | •Borate ester bonds •PPy | •Antimicrobial •Antioxidant •Anti-inflammatory •Pro-angiogenic | [172] | |

| DFO/ENZ@CPP hydrogel | Glu pH NIR | •Phenylboric ester bonds •Schiff base bonds | •Antimicrobial, antioxidant •Anti-inflammatory •Pro-angiogenic •pH regulation •Oxygen supply | [173] | |

| GOx@ZIF-90-Arg-loaded hydrogel | Glu pH | •GOx•ZIF-90•L-Arg | •Broad-spectrum antibacterial •Biofilm disruption •Anti-inflammatory •Neurovascular regeneration •Improved glucose tolerance •Promotion of collagen synthesis and cell proliferation •Controlled NO delivery avoiding oxidative stress •Hemostasis and tissue adhesion enhancement | [174] | |

| Cu-MOF/GOX-Gel hydrogel | Glu H₂O₂ Heat | •GOX •L-Arg | •Antibacterial via cascade catalytic ROS generation •Local glucose depletion •Controlled NO release •Angiogenesis promotion •Collagen deposition •Enhanced epithelial cell migration •Biocompatible and thermosensitive scaffold | [6] | |

| DPH3@INS@ZIF-8@PEG-TK hydrogel | Glu ROS pH | •Boronate ester bonds •PEG-TK•DA | •Insulin-mediated glucose regulation • ROS scavenging • Anti-inflammatory • Promotion of angiogenesis and collagen remodeling • M1-to-M2 macrophage polarization • Antibacterial activity • Hemostatic effect | [175] | |

| HPCG/PFD hydrogel | GlupH NIR (808 nm) | •Schiff base•Phenylboronate ester bond •GPC | •Photothermal antibacterial activity •Photodynamic antibacterial activity • Anti-inflammatory • Promotion of angiogenesis • Antioxidant activity | [176] | |

| Cu-TCPP(Fe)@Au@BSA hydrogel | GluH₂O₂pH | • Au@BSA• Cu-TCPP(Fe) | •Glucose consumption and pH reduction •Local •OH production for CDT-based antibacterial effects •Epithelialization and collagen regeneration • Antioxidant effect | [177] | |

| CRMs-hydrogel composite | MMP-9 enzyme Heat | •PVGLIG peptid | • Targeted antibacterial activity •MMP-9-responsive controlled release • Promotion of cell migration • Promotion of angiogenesis • Thermosensitive adhesion | [178] |

4.1.2 Dual cascade system

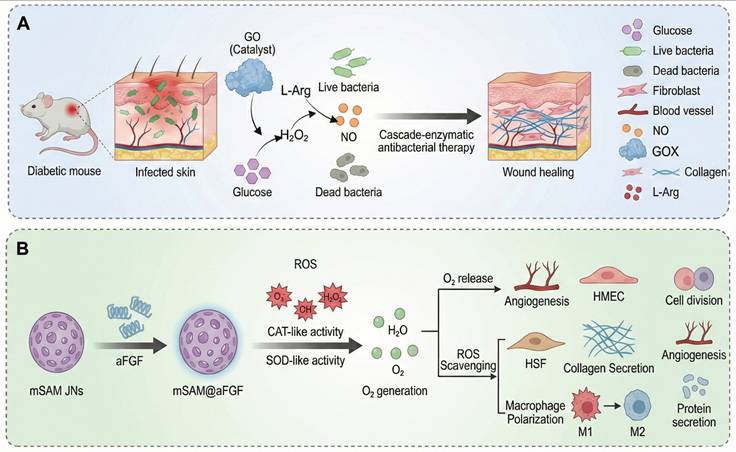

When the wound enters the subacute inflammatory phase, the vicious cycle of hyperglycemia, ROS overload, and hypoxia continues to be a critical limitation to wound healing. Dual cascade systems provide a major advance by allowing the modules of treatment to be activated in stages, which allows for energy self-supply and functional synergy. For example, the copper peroxide--GOx (CP@GOD) system uses GOx to catalyse glucose into H2O2, which is then decomposed by the CP nanozymes into hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and Cu2+ ions. The •OH result in a sterilization rate of over 99% against Staphylococcus aureus whereas Cu2+ ions trigger the HIF-1α pathway, which results in an 180% increase in the expression of the growth factor "VEGF" and, consequently, in the process of angiogenesis. In diabetic mouse models, this approach reduced the wound healing time to 14 days and greatly improved the vascular density [183]. Another innovative design, the photodynamic ROS-responsive nanogel (Ce6@ZIF-8), takes advantage of the acidic microenvironment in the wound to release the photosensitizer Ce6. When activated by NIR light, Ce6 produces oxygen and can be used to target eradication of MRSA. At the same time, the photothermal effect promotes the orderly deposition of collagen, thereby reducing the formation of scars [184]. The main benefit of these systems is the temporal control: the first infection control is performed by the antibacterial module, then the regeneration of factors to prevent interference with the therapeutic effect. However, synchronization of the kinetics of dual reactions is a technical challenge. For example, the injectable nanoreactor hydrogel Arg@Zn-MOF-GOx Gel (AZG-Gel) orchestrates two consecutive cascades: (1) GOx converts the hyperglycemic glucose into gluconic acid and H2O2, rapidly lowering local pH; (2) disassembly of Zn-MOF, triggered by the acid, releases arginine which consumes H2O2 to produce NO, thus ablating biofilms and inducing angiogenesis without the need for exogenous ROS. Although this all-in-one platform has a wound closure rate of 98.7% within 14 days, premature Zn-MOF degradation below pH 5.0 poses the risk of an NO burst that may induce transient cytotoxicity, underscoring the necessity of buffering microenvironments for clinical translation (Figure 6D) [159]. Similarly, the rate of H2O2 generation in the CP@GOD system should be carefully balanced with the release of Cu2+ to avoid excessive free radical damage to surrounding tissues. Moreover, endogenous catalase activity is in competition during the decomposition of H2O2, which could decrease the efficiency of the cascade [183].

Classification based on the number of cascade reactions. (A-C) Single-layer cascade reaction system. (A) pH-responsive hydrogel enabling Mg micromotor disintegration and therapeutic release under acidic diabetic wound conditions. (B) The glucose-responsive antioxidant hydrogel for diabetic wound healing. HA-PBA provides glucose sensitivity, enabling dynamic binding with myricetin. (C) ROS-responsive hydrogel. (D) Dual cascade system of a dual-responsive AZG-Gel hydrogel that responds to hyperglycemia and high pH by GOx-mediated glucose oxidation. (E) Multilayer cascade reaction system of a multi-responsive Ag-nGHC nanogel system, responding to hyperglycemia, hypoxia, and bacterial infection via a cascade of GOX/HRP/CAT enzyme reactions. Created in BioRender. Jia, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/f9fv3g2.

Dual-layer cascade hydrogels are made of different functional domains that act synergistically to spatially organize antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and regenerative effects. Compared to single layer systems, which provide fast response but mainly local action, these dual layer architectures can provide sequential therapeutic regulation and prolonged drug release. However, the fabrication of heterogeneous material layers of different swelling and degradation characteristics can cause interfacial instability and inconsistent cascade activation. Achieving synchronization of biochemical reactions within layers poses serious challenges in control, which raises processing complexity and hinders reproducibility. Despite promising therapeutic outcomes shown in preclinical studies, dual-layer cascade systems still suffer from challenges in structural optimization and scalable manufacturing. Therefore, future studies should aim to increase interfacial bonding, coordinate permeability between layers, and standardize production processes to increase stability and promote clinical translation.

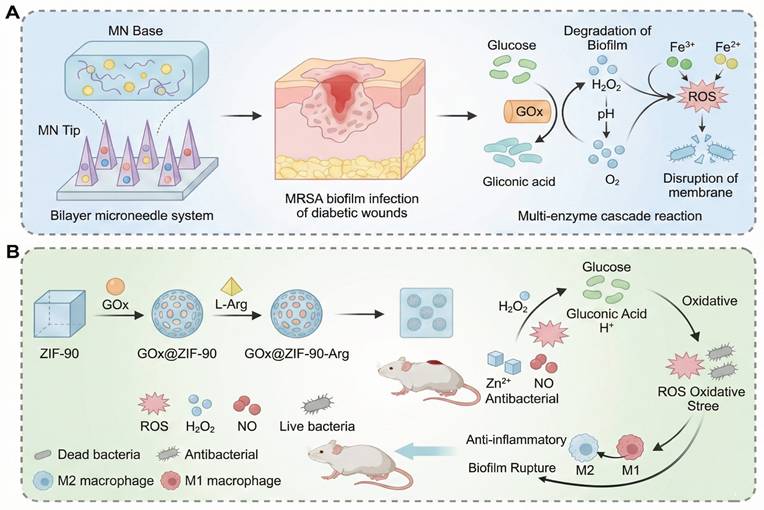

4.1.3 Multilayer cascade reaction system

The multiple cascade reaction system is a biomimetic catalytic network, which incorporates multiple enzymes or enzyme-like catalysts (e.g., nanozymes) in confined domains to build a multi-step, self-sufficient biochemical reaction chain for synchronous regulation of the diabetic wound microenvironment. Its main characteristics are: (1) multifunctional coupling, realized by synergistic enzyme catalysis (e.g., GOx/hydrogen peroxidase), nanomaterial catalysis (e.g., Pt/CeO2), and controlled release of bioactive molecules, which can achieve time-sequenced intervention, including glucose reduction, antioxidation, anti-inflammation, and tissue regeneration; (2) pathological responsiveness, induced by disease-specific signals such as hyperglycemia and ROS to achieve targeted metabolic regulation.

Given the multidimensional pathological characteristics of diabetic wounds such as hyperglycemia, inflammation, infection, and impaired angiogenesis, therapeutic systems need to have dynamic and synergistic intervention capabilities depending on wound stages. Single-layer cascade systems (e.g., glucose-activated antibacterial gels) consume glucose quickly and release Ag+ through enzymatic reactions, killing 99% of MRSA within 48 hours, but are not multifunctional enough for later stages of repair [112]. Dual cascade systems (e.g., pH/ROS-responsive hydrogels) that allow synergistic ROS clearance and sustained exosome release with temporal control to facilitate orderly anti-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic responses with a 40% increase in healing rate in animal models. Multi-layer cascade systems combine glucose response, antioxidation and epithelial regeneration, reducing wound closure to 8 days in diabetic mouse models, a good example of whole chain management [168]. The Ag-nGHC platform demonstrates a multilayer cascade with stage-adaptive responsiveness (Figure 6E) [160]. Its triple-enzyme nanogel structure allows for sequential glucose depletion, oxidative sterilization and oxygen regeneration, matching therapeutic activities to the wound healing process timeline, from infection control to tissue regeneration. Importantly, the high biocompatibility of the system stems from the incorporation of native enzymes, without the immunogenicity that is common with inorganic nanozymes. However, the inherent fragility of native proteins requires encapsulation strategies for in vivo sustained activity. This approach offers a new blueprint for enzyme-based therapeutics in diabetic wound care with potential applications beyond diabetic foot ulcers in burns and ischemic ulcers.

Hydrogel cascades multi-layer cascade hydrogels have emerged as a new advancement in regenerative medicine, in which the multiple layers with functional specifications permit hierarchical coordination of therapy because of spatially and temporally discrete responses [168]. These hydrogels are more functionally complex and allow sequential delivery of various biochemical signals than dual-layer systems. The increased structural hierarchy however causes problems including kinetic imbalances, diffusion mismatch across layer and buildup of intermediate byproducts all of which may cause incomplete or slow cascade activation [165]. Also, mechanical discrepancies and fabrication issues do not allow reproducibility and stability.

Moreover, excessive combination of various stimuli, catalytic modules and signaling pathways is dangerous to biological incoherence. The responsive units can interfere with each other, leading to kinetic interference or overlapping signals, which can disrupt the redox balance or result in immune overactivation. These unintended interactions may backfire on the therapeutic benefits and may augment the biosafety issues. Although multi-layer hydrogels are promising as programmable wound therapies, inter-module interference and the complexity of the system have inhibited their clinical translation. Thus, the functional simplification, decoupling of reaction pathways, and rational coordination of response modules should be made in the future to maintain controllability and biological harmony.

4.2 Classification based on cascade reaction mechanism

The pathological complexity of diabetic wounds demands systems of treatment capable of dynamically and multidimensionally controlling the underlying mechanisms [25, 105]. Depending on the principle of their triggering, the cascade reaction mechanism can be classified into three groups namely natural enzyme driven, biomimetic catalytic, and physicochemical response. Biocatalysis, material biomimetics and non-enzymatic cascade processes are precise interventions. The concerted integration of these mechanisms not only is commensurate to the pathological features stage-specific for the wound, but also overcomes the inherent limitations of single-modality treatments.

4.2.1 Enzymatic cascade reaction: precise activation of endogenous substrates in wounds

The cascade system based on natural enzymes has shown significant biocompatibility in acute phase applications. For example, the dual enzyme system of GOx and HRP converts high-concentration glucose into antibacterial reactive oxygen (·OH) through two-step catalysis, reducing the bacterial load on the wound surface by 98% in a diabetic mouse model (only 58% in the control group), while promoting collagen deposition to accelerate healing [186]. In this process, GOD first catalyzes glucose to produce H₂O₂, and then HRP decomposes it into ·OH with a broad-spectrum bactericidal effect, which not only achieves the goal of anti-infection, but also alleviates high glucose toxicity by reducing local glucose. Complementing the above GOD-HRP platform, an α-amylase/GOx-coupled chemodynamic patch has been engineered to sequentially degrade EPS polysaccharides and hyperglycaemic glucose. α-amylase first liquefies the biofilm matrix, liberating glucose that is immediately oxidised by GOx-immobilised MOF nanoneedles to generate local H₂O₂; subsequent Fenton-like chemistry converts H₂O₂ into cytotoxic •OH without exogenous H₂O₂, achieving 99.9 % MRSA eradication while lowering ambient glucose by 45 %. Nevertheless, the burst release of •OH at pH 5.5-6.0 transiently elevates oxidative stress, demanding ROS-quenching back-up layers to protect nascent granulation tissue (Figure 7A) [185]. Alternatively, a pH-driven NO-releasing cascade was recently constructed by co-encapsulating GOx and l-arginine within acid-labile ZIF-90 (GOx@ZIF-90-Arg) [158]. GOx-mediated glucose oxidation simultaneously consumes glucose and acidifies the microenvironment, triggering ZIF-90 disintegration to release Zn²⁺ and H₂O₂; the latter drives arginine oxidation to produce NO, which disperses 96% of pre-formed biofilms and enhances angiogenesis via cGMP signalling. The system attains 98.7% wound closure within 14 days, yet the rapid ZIF dissolution below pH 5.0 risks premature payload exhaustion, necessitating pH-buffering hydrogels or core-shell architectures to prolong therapeutic windows (Figure 7B) [174]. Enzymatic cascade reactions are considered to be one of the most biologically compatible strategies for wound regulation. These reactions use endogenous substrates to trigger sequential biochemical reactions with high spatial selectivity. In the setting of diabetic wounds, multi-enzyme systems, such as GOx/peroxidase or superoxide dismutase (SOD)/catalase cascades, have been shown to convert excessive glucose or ROS into controlled signals [158]. This process allows the modulation of oxidative stress, oxygen supply, and inflammation in situ. The efficacy of these designs in promoting self-sustaining biochemical feedback has been demonstrated, especially in promoting angiogenesis and tissue regeneration under conditions of hyperglycemia and hypoxia. However, the use of enzymatic cascade hydrogels is frequently limited by their complex kinetic processes and sensitivity to environmental variations. The activity and stability of natural enzymes can be affected by variation of pH, changes in temperature and by proteolytic degradation, resulting in unpredictable catalytic efficiency in vivo. Moreover, the over-integrated cascade networks with multiple catalytic modules can be affected by issues like kinetic crosstalk, substrate competition or imbalanced reaction rate. These issues may result in a reduction of controllability and potentially the production of unwanted intermediates. These effects can lead to local redox homeostasis or oxidative and immune stress which can reverse the desired therapeutic effects.

Multi-enzyme reactions are more specific to substrates compared to single-enzyme or photo/ROS-driven cascade systems, but they require strict stoichiometric control and local cofactor balance, which is a challenge to their standardization in clinical application. To address these issues, subsequent research should aim at stabilizing enzymes, either through biomimetic confinement or nanozymatic replacement, and rational pathway decoupling to guarantee catalytic precision and biological harmony in general.

4.2.2 Enzyme-mimetic cascade reaction: an engineering revolution in biomimetic catalysis