13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(6):3136-3172. doi:10.7150/thno.126489 This issue Cite

Review

Piezoelectric Heterojunction-driven Biomedical Revolution: From Construction Principles to Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications

1. Department of Ultrasound, The First Hospital of China Medical University, China.

2. Department of Ultrasound, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, China.

3. Department of Medical Oncology, the First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province 110001, China; Provincial key Laboratory of Anticancer Drugs and Biotherapy of Liaoning Province, the First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province 110001, China; Clinical Cancer Research Center of Shenyang, the First Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province 110001, China.

Received 2025-10-9; Accepted 2025-11-27; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Piezoelectric heterojunctions are emerging as a transformative class of smart biomaterials, revolutionizing biomedical applications through their unique mechano-electrical coupling effects. A central challenge hindering their full potential lies in the systematic understanding and utilization of their complex interfacial enhancement mechanisms. This review aims to establish a comprehensive framework that bridges fundamental principles to clinical translation. We begin with an in-depth analysis of the core enhancement mechanisms in piezoelectric heterojunctions, focusing on the synergistic interplay between the built-in electric field and band engineering that promotes efficient charge separation. We then provide a critical discussion of the ongoing debate surrounding their catalytic mechanism, reconciling the distinctions and connections between band theory and the surface screening charge model. Furthermore, we construct a multidimensional classification system centered on material dimensionality and composition to offer systematic guidance for the rational design and performance optimization of piezoelectric heterojunctions. In terms of applications, this review offers a comprehensive survey of the cutting-edge progress of piezoelectric heterojunctions in efficient cancer therapy, tissue regeneration, antibacterial strategies, and self-powered biosensing. We emphasize that the superiority of these heterojunctions stems from their ability to overcome the bottlenecks of low efficiency and mono-functionality inherent in single-component piezoelectric materials through sophisticated interface design, while also maximizing therapeutic outcomes via multimodal synergistic strategies. Finally, we critically analyze the formidable challenges this field faces concerning biosafety, scalable fabrication, and clinical translation, and offer perspectives on its future development toward intelligent theranostic systems. This review is intended to provide solid theoretical guidance and forward-looking insights for the design of next-generation, high-performance piezoelectric biomaterials.

Keywords: piezoelectric heterojunction, biomedicine, piezoelectric immunotherapy, piezocatalytic medicine

Introduction

Since its discovery in α-quartz crystals by the brothers Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880 [1], the piezoelectric effect has evolved from a fundamental physical phenomenon into a key driver of interdisciplinary research. The uniqueness of piezoelectric materials lies in their non-centrosymmetric crystal structure, which enables the bidirectional conversion between mechanical and electrical energy [2]. This property has led to their widespread application in traditional fields such as sensors [3, 4], actuators [4], and energy harvesters [5]. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of nanoscience and materials science, research on piezoelectric materials has achieved breakthrough progress in the biomedical field [6], ushering in the era of "Piezocatalytic medicine" (PCM). Its core principle involves using the charge carriers generated by piezoelectric materials under mechanical stress to catalyze redox reactions, producing Reactive oxygen species (ROS) for applications such as disease treatment, tissue repair, and antibacterial therapies [6].

However, first-generation piezocatalysts, primarily based on single-component materials, quickly encountered multiple bottlenecks. First, many high-performance inorganic piezoelectric materials (e.g., PZT) contain lead, posing potential biotoxicity risks [7]. Second, the inherent brittleness and rigidity of most inorganic materials limit their application in flexible biomedical devices [8]. More importantly, the limited charge output density and severe carrier recombination greatly restrict their therapeutic efficiency, while their single functionality has become a fundamental obstacle to meeting the demands of precision medicine [9, 10].

To overcome these limitations, the strategy of interface-engineered piezoelectric heterojunctions has emerged [11, 12]. By combining a piezoelectric phase with materials like semiconductors, metals, or two-dimensional (2D) materials, heterojunctions can utilize the built-in electric field (BIEF) and unique band alignment at the interface to spatially guide charge flow. This configuration significantly promotes charge separation efficiency while suppressing recombination [13, 14]. For example, Wang et al. [15] reported a BTO/MoS₂@CA core-shell structure whose catalytic performance under ultrasound was far superior to that of its single components. Furthermore, heterojunction design provides an ideal platform for multifunctional integration, enabling the combination of responses to multiple physical fields (light, sound, magnetism) with synergistic therapies, thus greatly enriching the therapeutic modalities and regulatory dimensions [16-18].

More revolutionarily, recent pioneering works have elevated the "interface" and "defects" themselves to a central role in the origin of the piezoelectric effect. Yang et al. discovered that in a metal-semiconductor Schottky junction, a device architecture that forms a rectifying barrier, a strong BIEF can break crystal symmetry. This induces a significant piezoelectric effect at the interface of a centrosymmetric semiconductor (like SrTiO₃) that is not inherently piezoelectric [19]. Building on this, Park et al. [20] demonstrated the disruptive power of defect engineering: by rearranging oxygen vacancies in a centrosymmetric oxide, they created an equivalent piezoelectric response that was orders of magnitude stronger. These works expand the origin of the piezoelectric effect from the traditional "crystal structure" to the realm of "interface and defect engineering." This not only fundamentally validates the importance of the heterojunction strategy but also opens up entirely new avenues for the design of piezoelectric biomaterials.

Given the rapid advancements in both the fundamental theory and applied research of piezoelectric heterojunctions, this review aims to systematically summarize their latest progress in the field of biomedical diagnostics and therapeutics. We will first elucidate their construction principles and enhancement mechanisms, focusing on the design concepts and performance characteristics of different types of heterojunctions. Subsequently, we will comprehensively review the cutting-edge applications of piezoelectric heterojunctions in biomedicine, including efficient cancer therapy, tissue repair and regeneration, antibacterial and infection control, and high-sensitivity biosensing. To ensure the comprehensiveness and timeliness of the content, we conducted a systematic search of major academic databases such as Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus, using keywords including but not limited to 'piezoelectric heterojunction', 'piezocatalysis', 'sonodynamic therapy', 'tissue regeneration', and 'biosensor'. While our primary focus was on high-impact research published in the last five years to capture the latest advancements, we also performed a retrospective inclusion of foundational and landmark studies from earlier years to provide essential historical and mechanistic context. Finally, we will discuss the challenges and future directions of the field, aiming to provide a theoretical basis and design insights for creating a new generation of high-performance biomedical devices and to promote the clinical translation of this promising research area (Figure 1).

Construction principles and enhancement mechanisms of piezoelectric heterojunctions

The performance enhancement of piezoelectric heterojunctions hinges on their interface engineering, particularly the band alignment and the formation of the BIEF. These two mechanisms collectively determine charge separation efficiency, carrier lifetime, and multi-field coupling capability [21].

Fundamentals of heterojunction interface engineering: Band alignment and BIEF

The efficacy of a piezoelectric heterojunction is fundamentally determined by its interfacial band alignment, which directly governs the separation, transport, and recombination behavior of photo-generated or piezo-generated charge carriers under external stimuli (e.g., mechanical stress, light illumination). Rational band engineering is key to achieving efficient charge separation, primarily classified into three classic types (Type-I, Type-II, Type-III) and some newly discovered special alignments (e.g., Type-V) [22, 23]. The working principles, representative material systems, and their regulatory roles in charge separation for each band alignment type are detailed below.

Basic types of band alignment and charge separation mechanisms

Type-I (straddling gap) occurs when the conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) of one material are completely encompassed within the bandgap of the other, forming a "nesting" structure. Both photo-generated electrons and holes migrate towards the material with the narrower bandgap, leading to spatial concentration of carriers in the same region. This is unfavorable for charge separation and promotes recombination. While unsuitable for catalysis, this structure allows rapid electron-hole recombination at the interface, making it applicable for light-emitting devices (e.g., LEDs) and lasers [24-26], but rarely used in PCM.

Type-II (staggered gap) refers to the staggered arrangement of the conduction and valence bands of the two materials at the interface. Typically, the CB and VB energy levels of one material are both lower than those of the other, forming a "staircase" structure. Photo-generated electrons spontaneously migrate from the higher CB to the lower CB, while holes migrate from the lower VB to the higher VB, achieving spatial separation of electrons and holes. This greatly suppresses recombination and provides more available carriers for catalytic reactions [27]. In the n-TiO₂/BaTiO₃/p-TiO₂ sandwich heterojunction, a Type-II band structure is formed, achieving a charge separation efficiency as high as 86.6%, far exceeding that of pure TiO₂ (43.6%) [28]. The 2D In₂Se₃/MoS₂ van der Waals (vdW) heterojunction also exhibits typical Type-II alignment. Due to the interlayer BIEF, its piezoelectric coefficient (d₃₃) is significantly enhanced [29].

Type-III (broken gap) occurs when the conduction band minimum of one material is lower than the valence band maximum of the other, resulting in completely misaligned bandgaps and band overlap at the interface. Electrons and holes can undergo tunneling, enabling separation, but interfacial recombination is usually rapid. This type is relatively uncommon in practical piezoelectric heterojunction design [30].

Recently, new band alignments have been discovered in some 2D material heterojunctions, such as Type-V alignment, found in partial van der Waals heterojunctions (e.g., PtSe₂/MoSe₂). Its valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) are distributed within the same material, but unique delocalized states are formed through interlayer orbital coupling (e.g., Se-pz and Mo-dz² hybridization). This structure maintains high stability under external electric fields or strain, providing new ideas for designing highly stable piezoelectric optoelectronic devices [31].

Strategies for tuning band alignment

Band alignment is not immutable and can be precisely tuned through various means to optimize charge separation efficiency. For example, applying biaxial strain to MoS₂ can change its bandgap from direct to indirect and significantly alter the absolute values of the band edges, thereby affecting the heterojunction's band alignment type and charge separation efficiency [32]. Applying an external vertical electric field can penetrate 2D materials and directly modulate their band structure, offering the possibility of dynamic, reversible tuning of band alignment [33]. For 2D material heterojunctions, the band alignment exhibits significant angle and frequency dependence on the number of layers. For instance, in MoS₂ multilayer structures supported on glass substrates, both perfect absorption and strong coupling light-matter interaction mechanisms can be simultaneously achieved without complex nanostructures. MoS₂ flakes exceeding 10 layers can achieve perfect absorption of TM-polarized light, with the absorption condition determined by the interaction between excitons and Fabry-Pérot photon modes. In thick MoS₂ (e.g., 97 layers), B and C excitons strongly couple with photon modes, forming exciton-polaritons, and significant Rabi splitting is observed [34].

Formation and enhancement mechanisms of the BIEF

The core physical basis for the performance improvement of piezoelectric heterojunctions lies in the formation and enhancement of the interfacial BIEF. This field is the key driving force for the efficient spatial separation of piezoelectric charges or photo-generated carriers and the suppression of recombination. Its strength and distribution directly determine the final output performance of the heterojunction. The formation of the BIEF primarily originates from charge rearrangement at the interface due to differences in the physical properties of the materials and can be significantly enhanced through various strategies [35, 36].

Origins of the BIEF

Contact potential difference and band bending

When two different materials (e.g., a piezoelectric material and a semiconductor) come into contact, their Fermi levels (E_F) must align at the interface to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium due to differences in their work functions and electron affinities. This process causes electrons to flow from the material with the smaller work function to the one with the larger work function until E_F is unified. Consequently, a space charge region (SCR) forms near the interface, accompanied by a corresponding built-in potential (V_bi) and band bending. The direction of this BIEF points from the semiconductor to the metal (for Schottky junctions) or from the n-type region to the p-type region (for p-n junctions), providing the core driving force for carrier separation [35, 37].

Contribution of piezoelectric polarization charges

The uniqueness of piezoelectric materials lies in their ability to generate significant polarization charges (direct piezoelectric effect) under applied mechanical stress [2]. These bound charges appear on the material surface or interface and strongly couple with and modulate the original BIEF [38]. For example, in a Schottky junction composed of a ZnO nanowire and an Au electrode, the positive polarization charges generated by applying compressive strain to ZnO can effectively lower the Schottky barrier height (SBH), significantly enhancing the electron injection efficiency from the semiconductor to the metal. This phenomenon, known as the piezo-electronic effect, was pioneered by Wang Zhonglin's team [39].

Interface polar symmetry breaking-induced piezoelectricity

Recent studies have found that even traditionally considered centrosymmetric semiconductors (e.g., SrTiO₃, TiO₂) can exhibit a piezoelectric response when forming a Schottky junction with a metal, due to atomic reconstruction and charge transfer at the interface leading to local symmetry breaking [38]. For instance, the BIEF originating from interface band bending in heterostructures can induce polar symmetry, resulting in significant piezoelectric and pyroelectric effects [19].

Recently, new band alignments have been discovered in some 2D material heterojunctions, such as Type-V alignment, found in partial van der Waals heterojunctions (e.g., PtSe₂/MoSe₂). Its valence band maximum (VBM) and conduction band minimum (CBM) are distributed within the same material, but unique delocalized states are formed through interlayer orbital coupling (e.g., Se-pz and Mo-dz² hybridization). This structure maintains high stability under external electric fields or strain, providing new ideas for designing highly stable piezoelectric optoelectronic devices [31].

Strategies for tuning band alignment

Band alignment is not immutable and can be precisely tuned through various means to optimize charge separation efficiency. For example, applying biaxial strain to MoS₂ can change its bandgap from direct to indirect and significantly alter the absolute values of the band edges, thereby affecting the heterojunction's band alignment type and charge separation efficiency [32]. Applying an external vertical electric field can penetrate 2D materials and directly modulate their band structure, offering the possibility of dynamic, reversible tuning of band alignment [33]. For 2D material heterojunctions, the band alignment exhibits significant angle and frequency dependence on the number of layers. For instance, in MoS₂ multilayer structures supported on glass substrates, both perfect absorption and strong coupling light-matter interaction mechanisms can be simultaneously achieved without complex nanostructures. MoS₂ flakes exceeding 10 layers can achieve perfect absorption of TM-polarized light, with the absorption condition determined by the interaction between excitons and Fabry-Pérot photon modes. In thick MoS₂ (e.g., 97 layers), B and C excitons strongly couple with photon modes, forming exciton-polaritons, and significant Rabi splitting is observed [34].

Formation and enhancement mechanisms of the BIEF

The core physical basis for the performance improvement of piezoelectric heterojunctions lies in the formation and enhancement of the interfacial BIEF. This field is the key driving force for the efficient spatial separation of piezoelectric charges or photo-generated carriers and the suppression of recombination. Its strength and distribution directly determine the final output performance of the heterojunction. The formation of the BIEF primarily originates from charge rearrangement at the interface due to differences in the physical properties of the materials and can be significantly enhanced through various strategies [35, 36].

Origins of the BIEF

Contact potential difference and band bending

When two different materials (e.g., a piezoelectric material and a semiconductor) come into contact, their Fermi levels (E_F) must align at the interface to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium due to differences in their work functions and electron affinities. This process causes electrons to flow from the material with the smaller work function to the one with the larger work function until E_F is unified. Consequently, a space charge region (SCR) forms near the interface, accompanied by a corresponding built-in potential (V_bi) and band bending. The direction of this BIEF points from the semiconductor to the metal (for Schottky junctions) or from the n-type region to the p-type region (for p-n junctions), providing the core driving force for carrier separation [35, 37].

Contribution of piezoelectric polarization charges

The uniqueness of piezoelectric materials lies in their ability to generate significant polarization charges (direct piezoelectric effect) under applied mechanical stress [2]. These bound charges appear on the material surface or interface and strongly couple with and modulate the original BIEF [38]. For example, in a Schottky junction composed of a ZnO nanowire and an Au electrode, the positive polarization charges generated by applying compressive strain to ZnO can effectively lower the Schottky barrier height (SBH), significantly enhancing the electron injection efficiency from the semiconductor to the metal. This phenomenon, known as the piezo-electronic effect, was pioneered by Wang Zhonglin's team [39].

Interface polar symmetry breaking-induced piezoelectricity

Recent studies have found that even traditionally considered centrosymmetric semiconductors (e.g., SrTiO₃, TiO₂) can exhibit a piezoelectric response when forming a Schottky junction with a metal, due to atomic reconstruction and charge transfer at the interface leading to local symmetry breaking [38]. For instance, the BIEF originating from interface band bending in heterostructures can induce polar symmetry, resulting in significant piezoelectric and pyroelectric effects [19].

Strategies for enhancing the BIEF

Synergistic enhancement via multi-field coupling

Coupling the piezoelectric effect with other effects like the photogenerated effect or thermoelectric effect can enhance the BIEF multi-dimensionally.

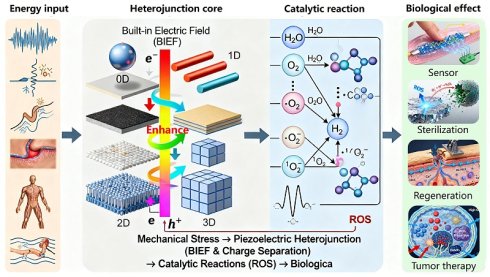

Schematic diagram of the classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions and their application scenarios in the biomedical field; applications in the biomedical field include efficient treatment of tumors, tissue repair and regenerative medicine, antibacterial and infection control, as well as sensors.

Photo-Piezoelectric Coupling: In the n-TiO₂/BaTiO₃/p-TiO₂ sandwich heterojunction, the piezoelectricity of the BaTiO₃ layer is activated under ultrasonic vibration. The generated piezoelectric polarization field aligns with the direction of the original p-n junction's built-in field, synergistically increasing the charge separation efficiency from 43.6% for pure TiO₂ to 86.6%. Under 800 rpm stirring, the photocurrent density increased from 2.13 to 2.50 mA∙cm⁻² [28].

Applying compressive strain to a p-SnS/n-MoS₂ heterojunction not only modulated its Type-II band offset but also increased the depletion region width, thereby enhancing the BIEF. This ultimately resulted in a device photoresponse corresponding to a built-in potential of 0.95 eV [41].

Dimensionality and interface control

Two-dimensional materials, due to their atomically flat surfaces and lack of dangling bonds, can form high-quality van der Waals heterojunctions, greatly reducing carrier trapping by interface defects. For example, constructing core-shell structures (e.g., BaTiO₃/TiO₂) can effectively expand the interfacial contact area and allow the BIEF to distribute uniformly within the shell layer. Studies show that such structures can improve the piezocatalytic degradation efficiency of toluene several times compared to physical mixtures [42].

Defect and doping engineering

Artificially introduced defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies, OVs) or doping can effectively modulate the Fermi level and carrier concentration of materials, thereby altering the strength of the BIEF. In TiO₂-based heterojunctions, an appropriate amount of OVs can act as electron donors, increase n-type conductivity, make band bending steeper, narrow the space charge region, and increase the built-in field strength. The synergy between atomic Ni co-catalyst and OVs increased H₂ production by 4 times [43].

Beyond the classic heterojunction types, researchers have drawn inspiration from natural photosynthesis to design more complex Z-scheme heterojunctions, which can achieve stronger redox capabilities and higher charge separation efficiencies. For example, Ji's group employed a clever "edge modification" strategy to grow Bi₂O₃ in situ on the edges of 2D BiOCl nanosheets, constructing an in-plane BiOCl/Bi₂O₃ Z-scheme heterojunction [44]. Under ultrasound, this system not only efficiently separates charges but also preserves holes with strong oxidizing power and electrons with strong reducing power. This allows it to catalyze a variety of reactions that are difficult for traditional catalysts to drive, effectively overcoming the limitations of the Tumor Microenvironment (TME). In another study, they used a similar strategy to construct a FeOCl/FeOOH Z-scheme heterojunction that achieved a "self-supplying H₂O₂" cascade catalysis. One component of the heterojunction oxidizes water to produce oxygen, while the other immediately reduces the generated oxygen to H₂O₂, providing a continuous supply of substrate for the subsequent Fenton reaction and greatly enhancing the therapeutic effect [45]. These sophisticated designs based on Z-scheme heterojunctions represent a frontier direction for maximizing catalytic performance through the rational tuning of interfacial band structures and charge transfer pathways.

Mechanistic controversies and a unifying perspective

Despite significant progress, the fundamental mechanism of piezocatalysis remains a subject of debate, primarily centered on two core issues.

One major point of contention is the origin of the active charges. Two competing models currently exist. The "band theory" model posits that the piezopotential modulates the semiconductor's band structure to separate internal charge carriers [35]. In contrast, the "screening charge model" argues that the catalytic activity originates from the dynamic desorption of external screening charges adsorbed onto the polarized surface [35]. These two models present a fundamental disagreement on the source of the charges. The "environmentally-mediated charge" model proposed by Xu et al., which suggests a synergistic interplay between both mechanisms, offers a potential path toward unifying these two perspectives [46].

Furthermore, confounding effects introduced by the driving source, especially ultrasound, constitute another key controversy. The observed catalytic activity is often attributed entirely to piezocatalysis, but it may be the result of multiple coupled mechanisms. The ultrasonic cavitation effect, which is central to sonodynamic therapy (SDT), can independently drive sonocatalysis [18, 47]. Concurrently, physical effects such as shockwaves or inter-particle friction could introduce competing tribocatalysis, or even negative synergistic effects [48]. Therefore, accurately decoupling the respective contributions of piezoelectric, sonochemical, and triboelectric effects is a major experimental challenge.

In the face of these controversies, establishing a unifying framework is crucial. The piezocatalytic process can be viewed as a four-step sequence: (1) energy input, (2) multi-mode conversion, (3) charge separation, and (4) surface reaction. Within this framework, regardless of the initial energy conversion pathway, the core role of heterojunction engineering is to optimize the critical "charge separation" step. Future research must shift from simple "phenomenological attribution" to "mechanism-driven" design, systematically elucidating the contribution of each mechanism by combining experimental and theoretical methods.

Classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions

Piezoelectric heterojunctions can be classified from multiple dimensions, including material dimensionality, composition/structure, interface bonding type, and functional properties. Current research frontiers primarily focus on low-dimensional piezoelectric heterojunctions, as they exhibit novel physical phenomena and superior performance not found in bulk materials.

Classification by material dimensionality

0D-2D piezoelectric heterojunction (Quantum dot/Nanodot compounded with 2D sheets)

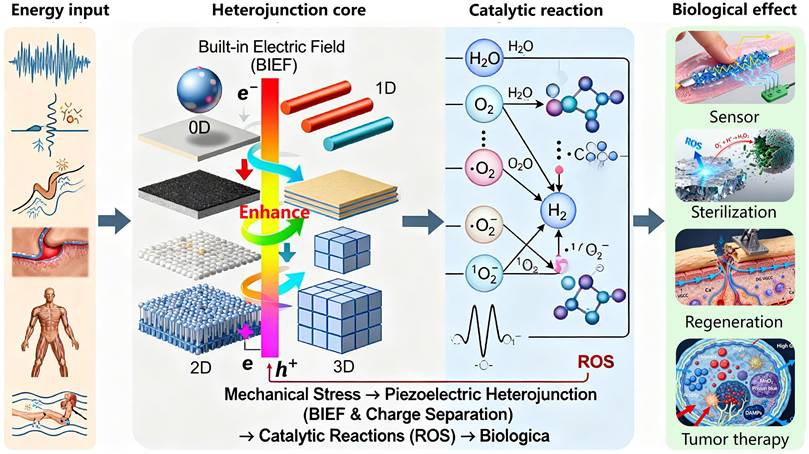

These materials involve uniformly loading zero-dimensional (0D) semiconductor quantum dots onto a 2D piezoelectric nanosheet substrate. The 0D piezoelectric nanodots can be carbon quantum dots (CDs), MoS₂ quantum dots, etc. For instance, Zhou et al. [49] sensitized Nb-doped tetragonal BaTiO₃ (BaTiO₃:Nb) with CDs. Piezoelectric polarization guides electrons to the semiconductor surface, limiting the recombination of photo-induced electron-hole pairs. The fastest generation of H₂O₂ was achieved with BaTiO₃:Nb/C (1360 μmol g_catalyst⁻¹ h⁻¹), which was 1.4 and 3.2 times faster than with BaTiO₃:Nb (972 μmol g_catalyst⁻¹ h⁻¹) and BaTiO₃/C (430 μmol g_catalyst⁻¹ h⁻¹), respectively (Figure 2A). Xiao et al. [50] constructed a dual-sensitized PDA/ZnO@MoS₂ QDs biosensor. By coupling MoS₂ quantum dots to ZnO, the detection limit for miRNA-182-5p was as low as 0.17 fM, with good selectivity, stability, and reproducibility (Figure 2B).

The advantages of such heterojunctions are that 0D nanodots provide a huge specific surface area, enabling dense interfacial contact with the 2D substrate. These interfaces are active sites for charge separation. The 2D sheet serves as an ideal supporting substrate, effectively preventing the agglomeration of 0D nanoparticles and fully exposing their active sites. Furthermore, 2D materials (especially graphene, MXene) often possess excellent conductivity, acting as "high-speed electron channels" to rapidly extract and transport charges generated by the 0D piezoelectric nanodots, greatly suppressing charge recombination. These heterojunctions are well-suited as efficient nano-sensitizers for tumor therapy or antibacterial applications, with the 2D sheet providing a good platform for biomolecule loading.

1D-2D piezoelectric heterojunction (Nanowire compounded with 2D sheets)

These heterojunctions involve compounding one-dimensional (1D) piezoelectric nanowires (NWs) or nanorods (NRs) with 2D materials. The 1D material can grow or attach vertically or parallel to the 2D plane. Schaper et al. [51] used a direct two-step chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method to confirm the uniform growth of ZnO nanowires (ZnO NWs) on a single-walled carbon nanotube network and produced denser, vertically oriented ZnO NWs on a graphene film (Figure 2C), suggesting potential applications in photocatalysts and biomedicine. In practical applications, the integration of PTO nanofibers with BOC nanosheets increased the contact area, amplified deformation, and enhanced the piezoelectric effect. Its photo-piezocatalytic efficiency was twice that of pure photocatalysis and three times that of piezocatalysis [52].

The characteristics of these materials are that 1D nanostructures possess excellent flexibility and mechanical strength, making them more prone to bending deformation under external force (e.g., ultrasound), thus generating a stronger piezoelectric potential. When combined with a 2D substrate, stress can be efficiently transferred throughout the heterojunction. Simultaneously, the 1D structure provides a longitudinal electron transport path, intertwining with the planar transport channels of the 2D material to form a three-dimensional, fast charge transport network, further promoting charge separation [53]. These materials hold great potential in flexible or implantable self-powered sensing. The 1D-2D structure easily constructs porous, high-specific-surface-area flexible films that conform to human tissues and harvest tiny mechanical energy.

2D-2D piezoelectric heterojunction (Van der Waals heterojunction)

These materials are formed by stacking two different two-dimensional materials through weak van der Waals forces and represent the current frontier and hotspot in 2D material research. For example, in a typical Type-II band alignment heterojunction (MoS₂/WS₂), photo-generated or piezo-generated electrons concentrate in the MoS₂ layer, while holes concentrate in the WS₂ layer, achieving intrinsic charge separation. Hole transfer from the MoS₂ layer to the WS₂ layer occurs within 50-100 fs after optical excitation [54, 55].

Traditional heterojunctions suffer from interface defects due to lattice mismatch, which trap charges. 2D-2D van der Waals heterojunctions are almost free from lattice mismatch constraints, forming atomically flat, dangling bond-free clean interfaces, greatly reducing charge recombination centers. By selecting different 2D materials (e.g., semiconducting MoS₂, metallic graphene, insulating h-BN) for combination [56, 57], the band alignment type (Type-I, II, III) of the heterojunction can be precisely designed to achieve directional charge separation. The electronic structure of such heterojunctions is highly sensitive to the number of layers, stacking angle, external electric field, or strain, offering the possibility for tunable, intelligent piezoelectric devices. Due to their ultra-thin, flexible, and transparent nature, 2D-2D heterojunctions have broad application prospects in wearable biosensors and micro/nano electromechanical systems (MEMS/NEMS), but large-scale preparation and transfer techniques remain challenging [58].

Classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions. (A) An illustration of the approach for catalytic production of H2O2 during simultaneous exposure to visible light and ultrasound with a catalyst based on BaTiO3:Nb and carbon quantum dots (CDs). Light irradiation of CDs results in the transfer of photoinduced electrons to the conduction band (CB) of BaTiO3:Nb, which in turn are involved in the reduction of O2. The electron donor C2H5OH quenches photoinduced holes (in the CDs and valance band [VB] of BaTiO3:Nb) and inhibits recombination of photoinduced charge carriers. Adapted with permission from [49], copyright 2022 The Authors. (B) PEC mechanism of ZnO, MoS2 QDs and PDA (before contact); the PEC mechanism of ZnO@MoS2 QDs and PDA/ZnO@MoS2 QDs (after contact). Adapted with permission from [50], copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. (C) Heterostructure growth beginning with (i) a CNT sample and (ii) a graphene sample dip-coated in the CCFe ink followed by (iii) CVD synthesis of ZnO NWs using the double-tube method, resulting in (iv) ZnO NWs/ CNTs and (v) ZnO NWs/Gr heterostructures. Adapted with permission from [51], copyright 2021 by the authors. (D) SEM cross-section images of PZT film deposited on Si/SiO2/Pt/Ti and mica substrate. Adapted with permission from [59], copyright 2024 by the authors. (E) Working diagram of graphene/PZT device. Adapted with permission from [59], copyright 2024 by the authors. F) I-V output electrical transport test curve of 100 nm thickness. Adapted with permission from [59], copyright 2024 by the authors.

3D-2D heterojunction (Bulk/Film compounded with 2D material)

These materials refer to the combination of three-dimensional (3D) piezoelectric bulk materials (e.g., ceramic plates, thick films) or thin films with 2D materials. The 2D material typically serves as a surface modification layer or an intermediate layer. For example, Bi et al. [59] integrated a PZT film onto a graphene substrate. With the generation of external force and strain gradient, the I-V output curve of graphene on the surface of the 100 nm thick PZT film exhibited rectifying characteristics due to the interfacial polarization mechanism (Figure 2D-F).

These materials combine the advantages of strong piezoelectricity from 3D bulk materials and the unique surface properties (high conductivity, catalytic activity) of 2D materials. Modifying the surface of 3D piezoelectric ceramics with 2D materials (e.g., graphene) can improve surface chemistry, act as a charge interlayer to accelerate extraction, or serve as a protective layer to enhance biocompatibility and stability. They are mainly used for high-performance composite piezoelectric thick films or devices, such as high-precision ultrasonic transducers or implantable energy harvesting devices [60, 61].

3D-3D heterojunction (Film compounded with film)

Heterojunctions formed by two three-dimensional materials (usually in thin film form). This is the most traditional form with the best compatibility with existing semiconductor processes. For instance, the carbon-silicon-carbon (C@Si@C) nanotube interlayer structure constructed by Liu et al. [62] had a capacity of ~2200 mAh g⁻¹ (~750 mAh cm⁻³), greatly exceeding commercial graphite anodes, and exhibited nearly constant Coulombic efficiency of ~98% over 60 cycles.

Such materials can be prepared using standard semiconductor processes like magnetron sputtering, pulsed laser deposition (PLD), and atomic layer deposition, facilitating large-area, uniform film integration. High-quality epitaxial or non-epitaxial interfaces can be obtained by precisely controlling deposition parameters. They are widely used in silicon-based MEMS biosensors for high-sensitivity detection of biomolecules (Table 1).

Classification by material composition and properties

Piezoelectric semiconductor-semiconductor type

These materials consist of two semiconductor materials, at least one of which possesses piezoelectric properties. This is the most abundant and extensively researched system. Examples include the classic n-ZnO/p-Si system, where ZnO is both a wide-bandgap semiconductor and a piezoelectric material, forming a p-n junction with silicon. Compared to bare Si NW electrodes, the n-ZnO/p-Si branched nanowires displayed photocurrent several orders of magnitude higher, and the doping concentration of the p-Si NW core influenced the photoelectrochemical cathode or anode behavior [63]. n-TiO₂/p-NiO is another common all-oxide p-n junction piezoelectric heterojunction. The wide-bandgap TiO₂ is primarily responsible for generating electron-hole pairs, while the p-type NiO acts as a hole collection layer. The band matching between the two promotes charge separation, exhibiting high activity in piezocatalytic degradation of organic matter [64].

These materials form p-n junctions or heterojunctions. Due to differences in work function and electron affinity, band bending occurs at the interface of the two semiconductors, forming a BIEF. This built-in field synergistically couples with the piezoelectric polarization field generated upon excitation of the piezoelectric material, greatly promoting the spatial separation of photo-generated or piezo-generated electron-hole pairs and suppressing their recombination. They offer high charge separation efficiency, and the band structure can be flexibly tuned through doping. However, issues like lattice mismatch and thermal mismatch may exist; interface state defects can become charge recombination centers.

Classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions by material dimensionality

| Classification | Schematic structure | Core advantages | Key challenges | Typical preparation methods | Potential biomedical applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0D-2D | Nanodots attached to sheets | High specific surface area, inhibits agglomeration, conductive channels | Uniform distribution control | Hydrothermal, in-situ growth, self-assembly | Nano-sensitizers (therapy) |

| 1D-2D | NWs/NRs intertwined with sheets | Efficient stress transfer, 3D charge network | Orientation and density control | CVD growth, transfer printing | Flexible/implantable sensors |

| 2D-2D (vdW) | 2D layered stacking | Clean interface, tunable band gap, external sensitivity | Large-scale prep. & transfer | Mechanical exfoliation, CVD, wet transfer | Wearable electronics, micro/nano devices |

| 3D-2D | 2D material covers 3D surface | Strong piezoelectricity + surface functionalization | Interface adhesion & stability | Transfer, coating, growth | High-performance composite devices |

| 3D-3D | Multilayer thin film structure | Mature process, easy integration | Lattice mismatch & stress | Sputtering, PLD, ALD | MEMS biosensors |

Piezoelectric material-semiconductor type

Composed of a strongly piezoelectric material (usually an insulator or wide-bandgap semiconductor) compounded with a conventional semiconductor material. For example, in PZT/MoS₂, the ferroelectric PZT provides a strong piezoelectric polarization field that can effectively modulate the carrier concentration and transport behavior in the conductive channel of the 2D semiconductor MoS₂, enabling the fabrication of piezoelectrically modulated transistor devices [65].

In these materials, strong piezoelectric materials generate extremely high piezoelectric potential under stress. This potential acts as a "gate voltage" to effectively modulate the interface barrier of the adjacent semiconductor i.e., the piezo-electronic effect. These heterojunctions exhibit strong piezoelectric output signals and significant modulation capability over the semiconductor channel. However, compatibility is poorer; strong piezoelectrics (e.g., PZT) often contain lead, raising biocompatibility concerns. They are currently mainly used for high-sensitivity mechanical sensing, e.g., electronic skin simulating human touch, with sensitivity far exceeding traditional sensors [66].

Piezoelectric-piezoelectric type

These heterojunctions are composed of two different piezoelectric materials. Examples include polymer/ceramic composites, which combine the advantages of polymers and ceramics, making them ideal for preparing flexible piezoelectric devices. BaTiO₃ nanoparticles dispersed in a PVDF matrix not only enhance the overall piezoelectricity but also induce the formation of more piezoelectric active β-phase in PVDF [67]. Furthermore, PVDF/BaTiO₃ composites regulated osteogenesis in electrical stimulation experiments on human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) [68].

These materials enable the superposition and coupling of piezoelectric effects. By designing the polarization directions of the two materials, their generated piezoelectric potentials can mutually enhance each other. More importantly, different piezoelectric materials may respond differently to stress of different frequencies or modes, potentially broadening the frequency response range or enabling more complex strain-to-electrical signal conversion. These heterojunctions achieve synergistic enhancement of piezoelectric performance, combining flexibility with high performance. However, polarization matching and stress transfer between different materials are design difficulties. They are ideal materials for flexible wearable energy harvesters and biomechanical sensors in biomedicine, capable of conforming to human skin or being implanted to harvest motion energy and monitor physiological signals.

Piezoelectric-metal type

These heterojunctions involve contact between a piezoelectric material and a metal, forming a Schottky junction or Ohmic contact. For example, in a ZnO Nanowire/Au electrode, when the ZnO nanowire is bent under pressure, positive and negative polarization charges are generated on the tensile and compressive sides, respectively. This asymmetrically changes the Schottky barrier at the metal-semiconductor contact, enabling a sensitive electrical response to external force [69]. In BaTiO₃ @ Au NPs, the local surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect of Au nanoparticles can synergize with the piezoelectric effect. Under photoacoustic (PA) synergy, hot electrons generated by LSPR can inject into the conduction band of the piezoelectric material, greatly enhanced catalytic reaction (e.g., antibacterial, tumor therapy) efficiency [70].

In these heterojunctions, the metal primarily serves as an electrode for collecting and extracting piezoelectric charges. In the case of forming a Schottky junction, the polarization charges generated by the piezoelectric effect directly modulate the SBH, significantly affecting current transport characteristics. This is another important manifestation of the piezo-electronic effect. These heterojunctions offer high charge collection efficiency and sensitive Schottky junction modulation. However, the metal-piezoelectric interface may experience fatigue or delamination under repeated stress. They are the fundamental building blocks for all piezoelectric biosensors in biomedicine and are also widely used in piezocatalytic therapy systems, such as SDT (Table 2).

The classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions is a multi-angle, intersecting system. For example, a heterojunction composed of a PZT film and MoS₂ can be simultaneously described as: a 3D-2D heterojunction, a piezoelectric material-semiconductor type heterojunction, and a modulation type or energy harvesting type heterojunction. This multi-dimensional classification method helps us understand its design concepts, preparation methods, and application potential from different perspectives. Current research frontiers mainly focus on low-dimensional (especially 2D-2D van der Waals) piezoelectric heterojunctions, as they exhibit many novel physical phenomena and excellent properties not found in bulk materials.

Classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions by material composition and properties

| Classification | Core mechanism | Typical material systems | Advantages | Challenges | Biomedical application focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piezo-Semiconductor-Semiconductor | Forms p-n junction, BIEF & piezoelectric field synergy | n-ZnO/p-Si, n-TiO₂/p-NiO | High charge sep. efficiency, tunable band gap | Lattice/thermal mismatch, interface states | Self-powered biosensing |

| Piezoelectric-Semiconductor | Strong piezo-potential modulates semiconductor channel (Piezo-electronic effect) | PZT/MoS₂, PMN-PT/GaN | Strong modulation capability, large output signal | Biocompatibility, interface compatibility | High-sensitivity mechanical sensing |

| Piezoelectric-Piezoelectric | Piezoelectric effect superposition & coupling, performance synergy | ZnO/AlN, PVDF/BaTiO₃ | Performance enhancement, broadened bandwidth, good flexibility | Polarization matching, stress transfer | Flexible wearable devices |

| Piezoelectric-Metal | Forms Schottky junction, modulates barrier; efficient charge collection | ZnO NW/Au, BaTiO₃@Au NPs | Simple structure, high charge collection efficiency | Interface fatigue, long-term stability | Basic sensing, catalytic therapy |

Classification by interface bonding type

Epitaxial heterojunction

These heterojunctions are formed when one material (the epitaxial layer) grows on another single-crystal substrate with a highly ordered crystallographic arrangement. The core feature is the presence of chemical bonding (covalent, ionic) at the interface, requiring the lattice constants and thermal expansion coefficients of the two materials to be as matched as possible to reduce interface misfit dislocation density. For example, GaN/AlN is a classic epitaxial system; both have wurtzite structures with small lattice mismatch (~2.4%) and are widely used in high-performance optoelectronic devices [71].

Through lattice matching, atoms in the epitaxial layer are forced to "mimic" the lattice arrangement of the substrate, achieving atomically smooth connections. Common preparation methods include molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), PLD, and metal-organic CVD. The interface has scantly defects (dangling bonds, vacancies), greatly reducing non-radiative recombination centers for carriers, allowing efficient charge transport across the interface. However, material selection is limited as lattice-matched partners must be found; preparation costs are extremely high, requiring single-crystal substrates and complex vacuum equipment.

Van der waals heterojunction (vdW heterojunction)

These heterojunctions are formed by stacking two-dimensional materials (e.g., graphene, MoS₂, WSe₂) through weak van der Waals forces. This is a "non-epitaxial" integration method where no chemical bonds form at the interface, thus completely free from lattice mismatch constraints. Examples include MoS₂/WS₂ [54, 55], In₂Se₃/MoS₂ [29], etc. MoS₂/WS₂ is a typical Type-II band alignment where electrons and holes automatically separate into different layers.

These heterojunctions are created using mechanical exfoliation and dry/wet transfer techniques, stacking different 2D materials like "building blocks" in a designed sequence. CVD can also be used to directly grow multilayer heterostructures. Since the layers are bound by strong covalent bonds internally and weak van der Waals forces interlayer, the exfoliated surfaces have no dangling bonds, resulting in nearly perfect interfaces that significantly reduce charge scattering and recombination. They allow free combination of any 2D material regardless of lattice constant and symmetry differences (e.g., graphene/h-BN/MoS₂) [72], providing unprecedented freedom for band engineering and functional design. These materials hold great potential for biomedical applications. Their ultra-thin, flexible, and transparent nature makes them ideal candidates for next-generation wearable health monitoring sensors and low-dimensional implantable neural interfaces.

Mixed-dimensional heterojunction

This type of heterojunction is a broad classification referring to the non-epitaxial combination of materials with different dimensionalities (0D, 1D, 2D, 3D). The interfacial bonding force can be van der Waals forces, physical adsorption, or weak chemical bonds (such as coordination bonds). Examples include 0D-2D (e.g., MoS₂ quantum dots coupled to ZnO [50]) and 1D-2D (e.g., ZnO nanowires grown on a graphene film [51]).

These heterojunctions are fabricated by integrating nanomaterials of different dimensions using relatively low-cost methods such as solution-based techniques (e.g., spin-coating, drop-casting), electrophoretic deposition, and in-situ growth (e.g., hydrothermal methods), thus eliminating the dependence on single-crystal substrates and complex vacuum equipment. While they can combine the advantages of materials from each dimension, the interface quality is often uncontrollable, typically containing numerous defects and dangling bonds that can act as charge recombination centers. Furthermore, poor interfacial contact may affect stress transfer and charge transport. They have very broad applications in the biomedical field. Their solution-processability is highly suitable for preparing flexible biosensing membranes, porous tissue engineering scaffolds (with integrated piezoelectric stimulation), and injectable piezocatalytic nanomedicines (0D-2D systems).

The classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions is a multi-angled, intersecting system. From the perspective of interface bonding, epitaxial, van der Waals, and mixed-dimensional heterojunctions each have their own preparation characteristics and application advantages. The current research frontier is mainly focused on low-dimensional (especially 2D-2D van der Waals) piezoelectric heterojunctions, as they exhibit many novel physical phenomena and excellent properties not found in bulk materials.

In summary, by classifying piezoelectric heterojunctions across multiple dimensions, we can more systematically understand the relationship between their structure and performance. To directly link these structural advantages with catalytic performance, we have systematically summarized a series of representative studies from recent years and compiled their key performance parameters in Table 3. This table provides a detailed comparison of the structural types, piezoelectric responses, stimulation conditions, ROS generation capabilities, and final biological effects of different heterojunction systems.

A deep analysis of Table 3 provides strong data-driven support for the superiority of piezoelectric heterojunctions. For instance, in terms of piezoelectric performance, the CFO@BFO magnetoelectric heterojunction constructed by Ge et al. [79]. utilizes the magnetostrictive effect to synergistically enhance the piezoelectric response, achieving an equivalent piezoelectric coefficient as high as 203 pm/V, far exceeding that of traditional single-component piezoelectric materials. In terms of catalytic efficiency, the construction of an Au@BaTiO₃ Schottky junction increased the ·OH production rate by 2.66 times compared to pure BaTiO₃ nanoparticles, a direct benefit of the enhanced charge separation promoted by the interfacial Schottky barrier. On the biological application level, the MoS₂/Bi₂MoO₆ heterojunction designed by Wang et al. [77]. achieved an antibacterial rate of over 99% against Staphylococcus aureus under ultrasound stimulation, demonstrating its great potential as a highly efficient antibacterial agent.

This quantitative data not only provides conclusive evidence for the performance advantages of piezoelectric heterojunctions but also reveals the feasibility of tuning catalytic activity through interface engineering. It offers a crucial reference for the rational design of high-performance piezoelectric biomaterials tailored for specific diagnostic and therapeutic needs.

Quantitative comparison of catalytic performance for representative piezoelectric heterojunctions

| Heterojunction system | Structure type | Piezoelectric properties | Stimulation conditions (US) | ROS generation | Catalytic efficiency | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BTO/MoS₂@CA [15] | Core-shell, 0D/2D | Typical butterfly curve | 1.0 MHz, 1.5 W cm⁻² | Strongest ·OH signal | POD-like activity: 76.36 U/mg | Tumor pyroptosis therapy |

| Ov-BOS [73] | Interlayered Self-Heterojunction | d*₃₃ = 203 pm/V | 1.0 MHz, 1.0 W cm⁻² | Detected ¹O₂, ·OH, ·O₂⁻ | Higher MB degradation rate vs BFO | Tumor pyroptosis therapy |

| Fe-SAs@PCN [76] | 0D/2D, Single-atom | d*₃₃ ≈ 5.8 pm/V | 40 kHz, 50 W | Enhanced ROS yield vs MoS₂ | Significant GSH depletion | Cuproptosis/Ferroptosis synergy |

| La-BFO [74] | Doped piezocatalyst | Typical butterfly curve | 1.5 W cm⁻² | Superior to ZIF-8 | Significant GSH depletion | SDT & Cuproptosis synergy |

| Bi₂MoO₆/PB-Au [78] | Ternary Heterojunction | d₃₃ = 20.3 pm/V | 1.0 MHz, 1.0 W cm⁻² | 4.8-fold ·OH yield vs PCN | ~91% RhB degradation in 120 min | Piezocatalysis-CDT synergy |

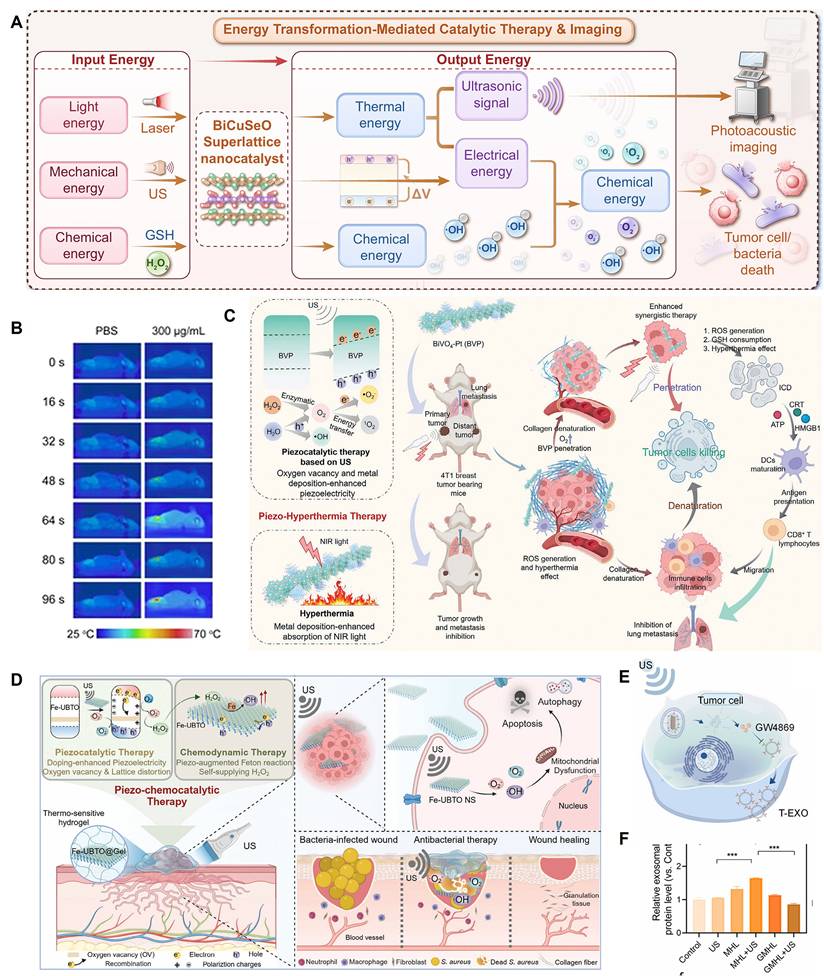

| BiCuSeO NSs [80] | 2D Natural Superlattice | Typical butterfly curve | NIR-II (PTE) & US (Piezo) | Strongest ·OH signal in ESR | Highest MB degradation | Tumor ferroptosis therapy |

| Fe-MoS₂ [12] | 2D Nanosheet w/ single-atom | d₃₃ ≈ 9.22 pm V⁻¹ | 1.0 MHz, 1.0 W cm⁻² | ¹O₂ gen. (60.22% DPA degradation) | GSH depletion & O₂ production | Hypoxia-relieved SDT |

| Cu-based2D MOF [75] | 2D MOF | Typical butterfly curve | 1.0 W cm⁻², 4 min | Detected ·OH and ·O₂⁻ | Significant MB degradation | Tumor therapy |

| Au@BaTiO₃ [77] | Schottky junction | Tetragonal phase (XRD) | 1.0 MHz, 1.5 W cm⁻² | Detected ¹O₂, ·O₂⁻, ·OH | Complete eradication of bacteria | PTE antibacterial & Piezo anticancer |

| CoFe₂O₄@BiFeO₃ [79] | Core-shell, Magnetostrictive | Typical butterfly curve | AMF (1.6 mT) | 2.66-fold ·OH yield vs BTO | >99% antibacterial rate (E. coli & S. aureus) | Antibacterial & Wound healing |

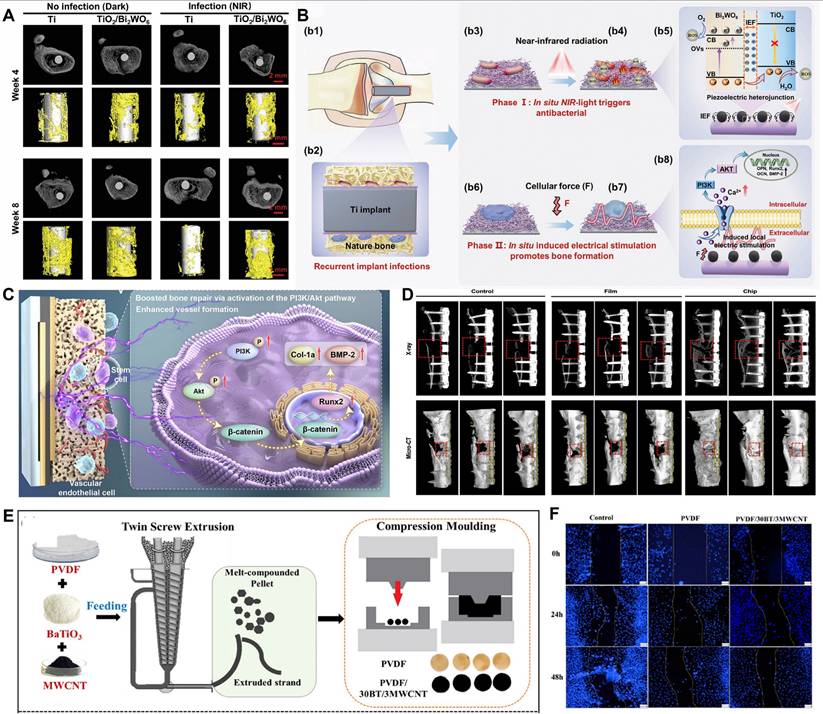

| TiO₂/Bi₂WO₆ [82] | 1D/2D Heterojunction | d₃₃: 8.122 pm V⁻¹ | NIR & Cellular force | Highest DCFH-DA signal | >98% antibacterial rate | Antibacterial & Bone regen |

Guideline for selecting piezoelectric heterojunctions for specific biomedical applications

| Application scenario | Key clinical challenges and requirements | Recommended heterojunction strategy | Rationale / Design principle | Representative system |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep-tissue tumor therapy | Low penetration depth of stimuli; Hypoxia & high GSH in TME | Type-II or Z-scheme heterojunctions responsive to deep-penetrating energy (US, magnetic field). Integrate with O₂-generating/GSH-depleting components. | Maximize charge separation for high ROS yield. Overcome biological barriers to enhance therapeutic efficacy. US/magnetic field ensures deep energy delivery. | BMO/PB-Au [78]; Fe-MoS₂ [12] |

| Infected bone defect repair | Bacterial infection hinders regeneration; Need for simultaneous antibacterial and osteogenic effects. | Design multi-functional heterojunctions with both piezocatalytic antibacterial and piezo-electrical osteogenic activities. | Utilize ROS for broad-spectrum bacterial killing. Utilize sustained piezoelectric potential to mimic endogenous electrical cues and promote osteoblast differentiation. | TiO₂/Bi₂WO₆ [82] |

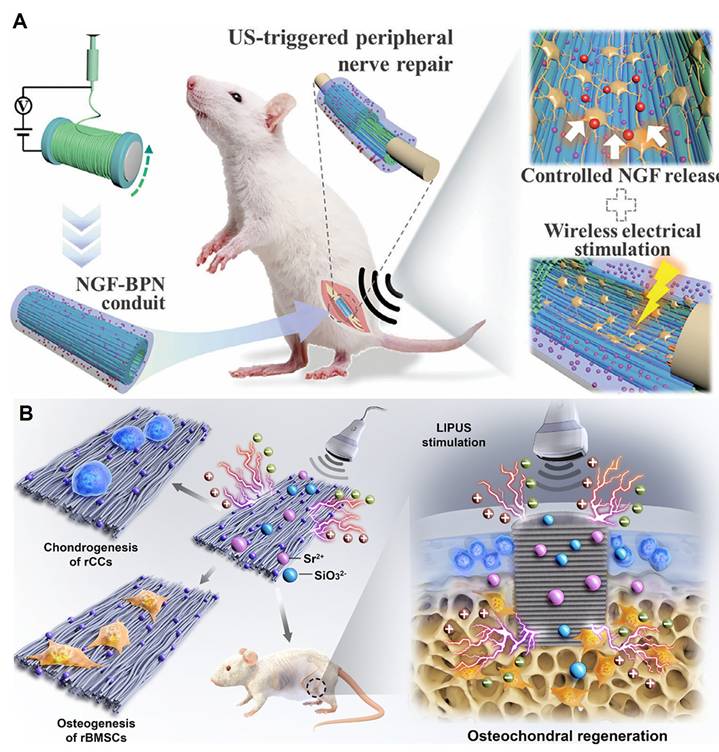

| Nerve regeneration | Slow axonal growth; Need for directional guidance and sustained neurotrophic stimulation. | Fabricate aligned nanofiber-based piezoelectric scaffolds. Integrate with controlled release of growth factors. | Aligned topography provides physical guidance for axonal extension. Piezoelectric stimulation promotes NSC differentiation and neurite outgrowth. | P(VDF-TrFE)/BTNP nanofibers in hydrogel [61,83]; |

| Antibacterial surface coating | Implant-associated infections; Biofilm formation. | Construct robust and stable heterojunction coatings (e.g., core-shell) on implant surfaces. | Provide on-demand, non-leaching antibacterial action upon mechanical stimulation (e.g., body movement, US cleaning), preventing biofilm formation without systemic antibiotic release. | Au@BaTiO₃ [77] |

| Wearable health monitoring | Need for self-powered, flexible, and sensitive sensors. | Develop flexible polymer-based heterojunctions (e.g., PVDF composites) with high piezoelectric output. | Conform to skin and detect subtle physiological pressures (pulse, respiration). Convert mechanical energy into readable electrical signals without external power. | PVDF/BTO [67,68]/ZnO[130] |

Frontiers in biomedical applications of piezoelectric heterojunctions

Having systematically elucidated the construction principles, enhancement mechanisms, and multidimensional classification of piezoelectric heterojunctions, we can now appreciate the physicochemical basis for their enhanced performance. This chapter will focus on the cutting-edge applications of these remarkable materials in several biomedical fields, with a primary emphasis on their most representative application: efficient cancer therapy. We will systematically review how piezoelectric heterojunctions, through core mechanisms like piezocatalysis and in combination with various synergistic strategies, can achieve precise and effective diagnosis and treatment of diseases.

The roles that piezoelectric heterojunctions play in different biomedical applications are diverse, and consequently, the focus of material design varies significantly. To visually present this correspondence, Table 4 systematically summarizes the core challenges faced in mainstream application scenarios (such as cancer therapy, tissue regeneration, etc.) and lists the corresponding material design strategies and key performance parameters. This summary is intended to provide researchers with a clear reference framework to facilitate the efficient development of materials tailored for specific clinical needs.

Efficient cancer therapy

As one of the leading causes of death worldwide, cancer and its treatment remain a central focus of medical research. Piezocatalytic therapy, an emerging paradigm that utilizes mechanical stimuli such as ultrasound to drive piezoelectric heterojunctions to kill tumor cells, has shown tremendous application potential. This approach has become a particularly noteworthy independent research direction for the treatment of deep-seated tumors, such as the notoriously difficult-to-treat glioblastoma (GBM). Several reviews have systematically reported on its progress and challenges [85].

Ultrasound-mediated piezocatalytic therapy

ROS-based synergistic catalysis

The core killing mechanism of ultrasound-mediated piezocatalytic therapy is the generation of ROS through the catalysis of water and oxygen molecules, which induces oxidative damage in tumor cells. The early strategy of using piezoelectric materials as sonosensitizers is referred to as SPDT [18]. In this process, ultrasound excites the piezoelectric material to generate electron-hole pairs, and the heterojunction structure promotes their separation, thereby enhancing the efficacy of SDT [86]. Current research has shifted its focus toward constructing multifunctional piezoelectric heterojunctions to maximize therapeutic effects by synergizing multiple catalytic mechanisms.

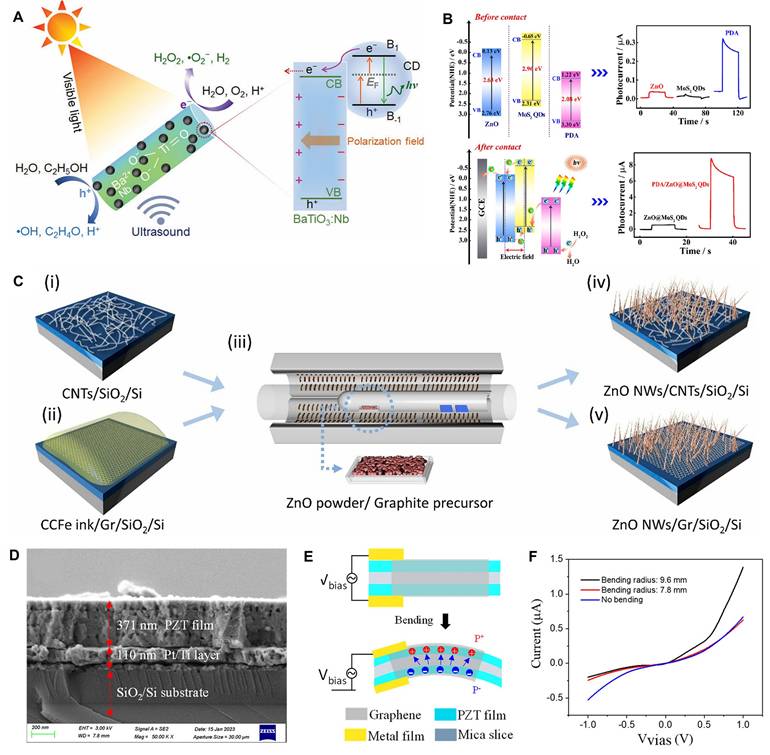

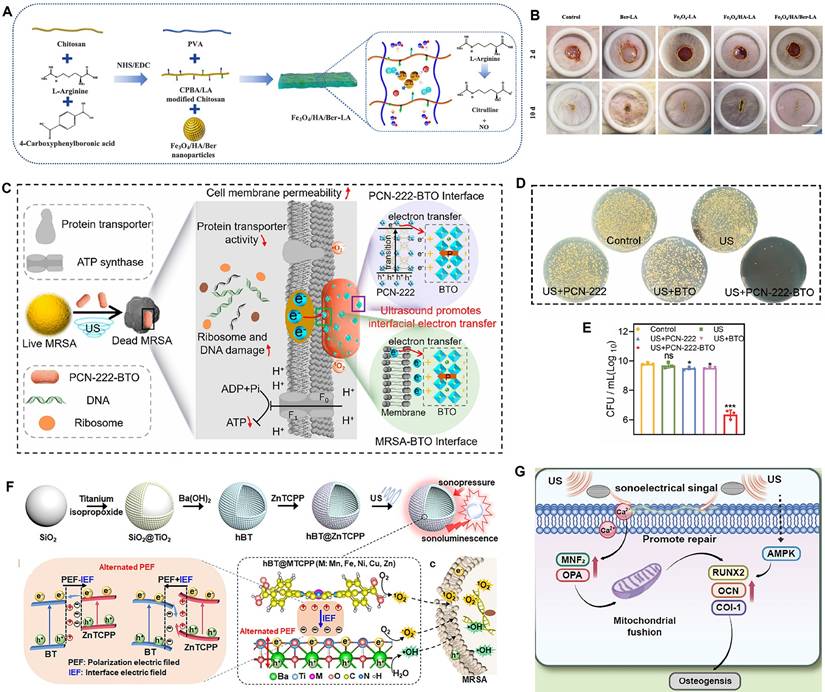

One major synergistic strategy is to integrate piezocatalysis with multiple enzyme-like activities. For example, Li et al. constructed an oxygen-vacancy-engineered bismuth silicate nanosheet (Ov-BOS NSs) with an alternating heterolayer structure [73]. By introducing OVs, the material's piezoelectric strain coefficient (d₃₃) reached as high as 203 pm/V, significantly enhancing charge separation and ROS generation efficiency under ultrasound. Concurrently, the Ov-BOS NSs also possessed peroxidase- and catalase-like activities, enabling synergistic ROS production within the TME. This induced tumor cell pyroptosis via the caspase-3/GSDME pathway, achieving a tumor inhibition rate of 96.1% (Figure 3A). Similarly, Zhao et al. constructed a manganese oxide (MnOx)-modified bismuth oxychloride (BiOCl) piezoelectric heterojunction [76]. In this system, the MnOx component, through its multiple enzyme-like activities, synergistically depleted the intracellular antioxidant glutathione (GSH) and catalyzed the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, thereby amplifying the oxidative stress generated by piezocatalysis. The system demonstrated good biocompatibility and a significant tumor suppression effect in a 4T1 breast cancer mouse model, with an inhibition rate of 70% (Figure 3B).

Overcoming the barriers of the TME, particularly hypoxia and antioxidant defenses, is another critical synergistic strategy. Yang et al. constructed a multifunctional Bi₂MoO₆/Prussian blue-Au (BMO/PB-Au) piezoelectric nanoplatform that synergistically enhanced SDT efficacy through three mechanisms [78]. First, the BMO/PB-Au heterojunction effectively promoted charge separation, increasing ROS yield. Second, the PB-Au component possessed both catalase (CAT)-like and glutathione oxidase (GSHOD)-like activities, which not only decomposed endogenous H₂O₂ to relieve hypoxia but also depleted GSH to weaken the tumor's antioxidant defenses. Finally, tumor targeting was achieved by cloaking the nanoparticles with cancer cell membranes (CM). This platform systematically addressed the traditional limitations of SDT by integrating piezocatalysis with chemical catalysis (Figure 3C). Building on this, Zhang et al. combined this strategy with starvation therapy and nanomotors, constructing a Janus-structured hollow barium titanate-Au nanoparticle (C-hBT@Au-G) [87]. In this design, the piezoelectric effect, a cascade enzyme catalysis (GOx/CAT), and nanomotor motion formed a self-enhancing cycle: the piezoelectric effect enhanced the enzyme catalytic efficiency, and the enzymatic product (O₂) in turn enhanced the piezodynamic therapy (PZDT) effect and propelled the nanomotor. This design broke through multiple drug delivery barriers, achieving highly efficient synergy between piezodynamic and starvation therapies.

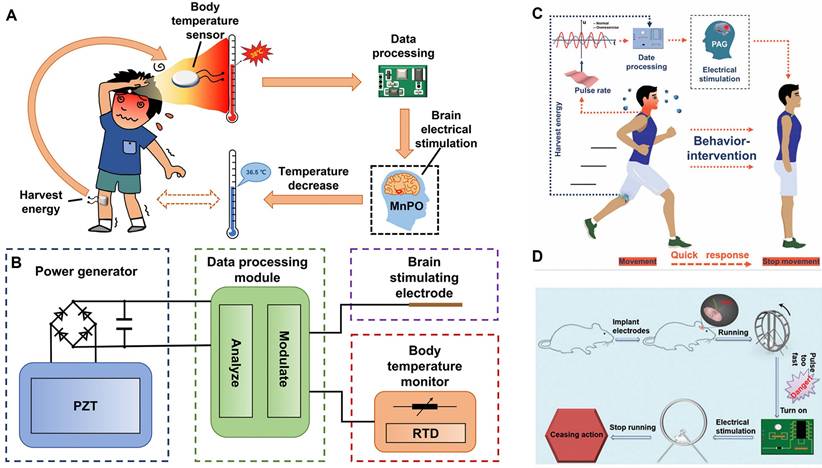

In addition to the commonly used external ultrasound drive, utilizing endogenous physiological mechanical stress to activate piezocatalysis is an emerging frontier. Xu et al. innovatively developed a piezocatalytic nanozyme (O₃P@LPYU) activated by respiratory rhythm for the treatment of malignant pleural effusion (MPE) [88]. By doping a metal-organic framework (MOF), UIO-66, with the rare-earth element ytterbium (Yb), they increased the material's d₃₃ from 67 pm/V to 256 pm/V. This system was able to use the pressure changes in the pleural cavity during the respiratory cycle (-3 to -10 mmHg) as a driving force to efficiently catalyze the generation of a large amount of ROS, inducing immunogenic death of tumor cells. In an MPE mouse model, the system showed excellent retention (half-life of 5 days) and therapeutic efficacy, with negligible systemic toxicity (Figure 3D). Although there is considerable research on using self-powering or autonomous motion for energy harvesting [89, 90], sensing [91], and tissue repair [92, 93], reports of its direct application in cancer therapy are still scarce, representing a direction with great future potential.

Inducing ferroptosis and cuproptosis

Beyond the non-specific oxidative damage caused by ROS, a promising new strategy that has garnered significant attention in recent years is the use of piezoelectric heterojunctions to precisely induce specific forms of programmed cell death, such as ferroptosis, cuproptosis, and pyroptosis.

Zhang et al. [12] constructed a 2D molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) piezocatalyst doped with single iron atoms (Fe-MoS₂). The single-atom iron doping effectively modulated the electronic structure and piezoelectric polarization behavior of MoS₂, significantly increasing its piezoelectric coefficient (d₃₃ enhanced from 6.16 pm/V to 9.22 pm/V). Under ultrasound, this material exhibited excellent piezocatalytic performance and also possessed multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, including peroxidase-, GSHOD-, oxidase-, and CAT-like activities. This combination synergistically produced a large amount of ROS while depleting GSH. The ROS burst and GSH depletion collectively disrupted intracellular copper ion homeostasis, inhibited ATP7B function, and promoted the accumulation of endogenous copper ions in mitochondria. This, in turn, induced cuproptosis, a form of copper-dependent cell death, while synergistically triggering ferroptosis and ferritinophagy. The material demonstrated significant tumor suppression effects in both in vitro and in vivo experiments. This study represents the first strategy for piezocatalytically inducing cuproptosis without an external copper source, providing a new paradigm for the application of piezoelectric materials in cancer therapy and broadening the design of cuproptosis-related nanomedicines (Figure 3E). In a different approach, Zhong et al. [75] used a 2D copper-based substrate for a MOF. Through coordination with dimethylimidazole, the resulting CM was endowed with piezoelectric properties. Under ultrasound, the copper ions in the CM could induce cuproptosis in tumor cells, which, combined with the generated ROS, accelerated cell death.

Piezo-catalytic therapy. (A) MechanismofOv-BOSNSs-mediated induction of tumor cell pyroptosis, consisting of four key steps. Step 1. The extraordinary piezoelectric performance caused by self-heterojunction accelerates and enhances charge carrier generation. Step 2. The band redistribution of Ov-BOS NSs caused by specific electron traps facilitates the spatial guided transport and stratified storage of sono-excited electrons and holes across the alternating [Bi2O2] and [SiO3] layers, respectively, thereby suppressing the recombination of charge carriers. Step 3. Synchronized sono-piezocatalytic pathways of Ov-BOS NSs boost the ROS generation. Step 4. Ov-BOS NSs impair mitochondrial function in cells, leading to caspase-3/GSDME-dependent pyroptosis. Adapted with permission from [73], copyright 2025 Wiley-VCH GmbH. (B) Schematic diagram of the piezoelectric M-BOC@SPNSs for enhanced SDT against cancer. Adapted with permission from [76], copyright 2023 Elsevier Inc. (C) The piezoelectric semiconductor acoustic sonosensitiser BMO/PB-Au@CM NPs that integrate superior CAT-like enzyme and special GSHOD-like enzyme into one system to achieve efficient antitumour SDT efficacy. Adapted with permission from [78], copyright 2024 Elsevier Inc. (D) Synthesis of O3P@LPYUNPs for enhancing physiological IPP-responsive piezoelectric catalytic therapy. NPs nanoparticles, IPP intrapleural pressure, NH2-BDC 2-amino-1,4-benzenedicarboxylic acid, DMF dimethylformamide, PFD perfluorodecalin, VB valence band, CB conduction band, ROS reactive oxygen species. Adapted with permission from [88], copyright 2025 The Author(s). (E) Schematic representation demonstrating the Fe- MoS2 enabled piezocatalytic and enzyocatalytic therapy synergistically induce tumor cell death through cuproptosis. Adapted with permission from [12], copyright 2025 The Authors. (F) La-doped BFO piezoelectric nanozyme triggers the enlarged ROS generation by lowering the band gap. Adapted with permission from [74], copyright 2025 The Author(s).

Li et al. [74] innovatively designed a lanthanum (La)-doped bismuth ferrite (La-BFO) piezoelectric nanozyme. Through a synergistic strategy of specific element doping and vacancy engineering, they achieved efficient induction of pyroptosis in breast cancer cells. The core features of this system were twofold: the introduction of La not only narrowed the bandgap of BFO (from 2.14 eV to 2.01 eV) and created OVs, significantly enhancing the efficiency of ROS generation (including ·OH, ·O₂⁻, and ¹O₂) under ultrasonic excitation; concurrently, the released La³⁺ ions could specifically damage the lysosomal membrane, synergizing with ROS to activate the Caspase-1/GSDMD pathway. This dual amplification of the pyroptotic effect overcame the apoptosis resistance of tumor cells. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments confirmed that the system effectively inhibited tumor growth (the intratumoral injection + ultrasound group achieved an inhibition rate of 76.7%) and enabled computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) dual-modal imaging guidance, thanks to the presence of Bi and Fe elements. This work provides a new paradigm for tuning the performance of piezoelectric materials through elemental doping and for combining ion therapy with catalytic therapy to induce inflammatory cell death (Figure 3F).

Piezocatalytic immunotherapy

Piezocatalytic immunotherapy [17, 94], which combines piezocatalysis with immunotherapy, is an emerging and highly promising direction in recent years. Its core strategy is to convert immunologically suppressive "cold tumors" into immunologically active "hot tumors" through a dual-action mechanism. On one hand, piezocatalysis generates ROS to induce ICD, releasing tumor antigens to initiate an immune response. On the other hand, the local micro-electric field or related biological effects generated by the piezoelectric effect can directly modulate the TIME. This section will review the latest progress from these two aspects.

Inducing immunogenic cell death

Inducing ICD in tumor cells is the crucial first step in activating anti-tumor immunity. In addition to traditional apoptosis, growing evidence suggests that specific forms of programmed cell death, such as ferroptosis, pyroptosis, and PANoptosis, are also highly immunogenic. For example, research by Cheng et al. [95] demonstrated that ferroptosis induced by a Bi₂MoO₆-MXene piezoelectric heterojunction could effectively promote the release of damage-associated molecular patterns, thereby activating downstream dendritic cell maturation and anti-tumor immunity. Therefore, precisely regulating cell death pathways via piezocatalysis is a core strategy for achieving efficient piezocatalytic immunotherapy.

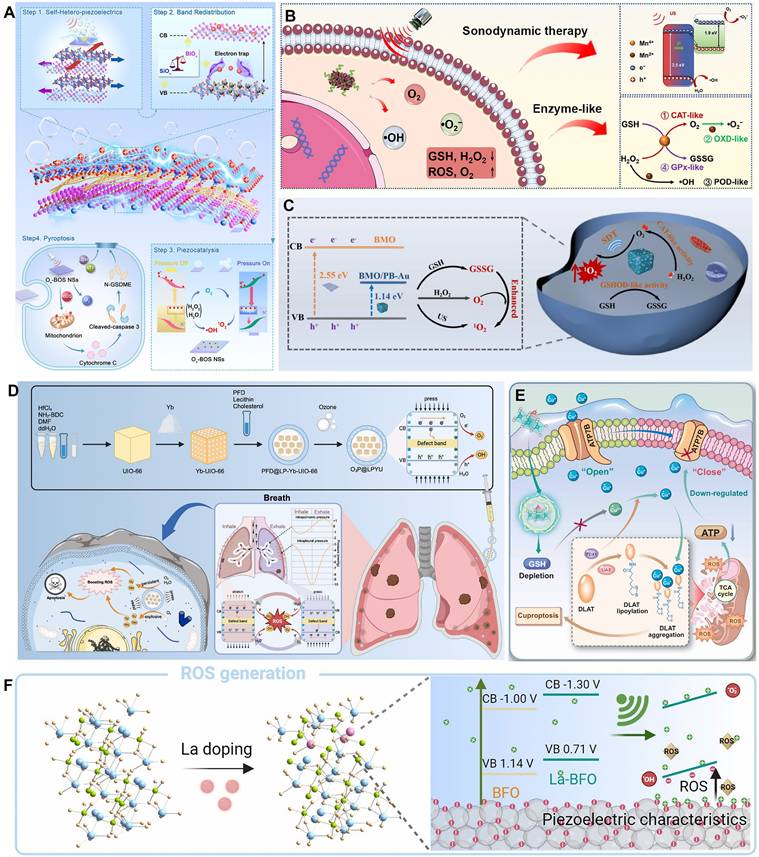

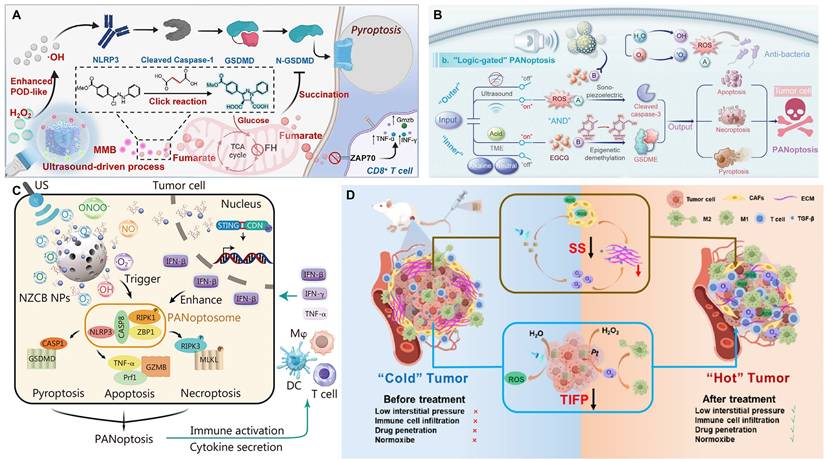

Targeting pyroptosis, Niu et al. [96] constructed an ultrasound-driven, piezo-enhanced iron-based single-atom nanozymeco-loaded with triphenylphosphine and the bioorthogonal fumarate reagent MMB. Under ultrasound, the piezoelectric effect of BFTM significantly enhanced the peroxidase-like activity of the single iron sites, generating a large amount of ·OH to induce caspase-1/GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis. Simultaneously, MMB consumed intracellular fumarate via a 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction. This not only prevented the succination of the key cysteine in GSDMD to enhance pyroptosis but also restored ZAP70 phosphorylation to normalize the T-cell receptor signaling pathway, thereby revitalizing CD8⁺ T-cell function (Figure 4A). Cai et al. [97] constructed a biodegradable manganese-doped hydroxyapatite (Mn-HAP). Under ultrasonic excitation, the released Ca²⁺ and ROS promoted pyroptosis, while Mn²⁺ activated the cGAS-STING pathway, triggering innate immunity and further enhancing the pyroptosis-induced immunotherapeutic effect. Wu et al. [98] constructed a narrow-bandgap Ir-C₃N₅ nanocomposite by coordinating Ir(tpy)Cl₃ onto nitrogen-rich C₃N₅ nanosheets, which significantly enhanced the material's piezocatalytic performance and oxygen self-supply capability. Under ultrasound, the composite efficiently generated ROS and catalyzed the decomposition of endogenous H₂O₂ into O₂, alleviating the hypoxic TME. The Ir-C₃N₅ targeted lysosomes, where the piezoelectric effect induced lysosomal rupture, inhibited autophagy, and activated the caspase-1/GSDMD-N-mediated pyroptosis pathway. This process released DAMPs, induced ICD, activated both innate and adaptive immune responses, significantly inhibited primary, distant, and metastatic tumor growth, and established long-term anti-tumor immune memory.

Pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis are collectively referred to as PANoptosis [99]. Xu et al. [100] developed a multifunctional nanocatalyst based on mesoporous piezoelectric barium titanate (mtBTO), named NZCB NPs. Under ultrasound excitation, it could efficiently generate reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS/RNS), such as ·O₂⁻, NO, and ONOO⁻, thereby inducing highly immunogenic PANoptosis in B16 melanoma cells. The nanosystem could also release the STING agonist CDN and Zn²⁺, synergistically activating innate and adaptive immune responses, promoting M1-type macrophage polarization and DC maturation, and remodeling the TME (Figure 4B). Meanwhile, Wang et al. [101] constructed a composite scaffold (STE-BG) based on an "external piezoelectric-internal epigenetic" logic gate. By combining porous piezoelectric SrTiO₃ nanoparticles (MeST) loaded with the epigenetic modulator EGCG with a 3D-printed bioactive glass scaffold, they achieved precise PANoptosis induction and immunotherapy for osteosarcoma, with a tumor inhibition rate of approximately 73.47% (Figure 4C). Zhong et al. [102] developed a manganese-doped hafnium oxide (HMO, 20% Mn) piezoelectric nanocatalyst. The Mn doping introduced OVs, reduced the bandgap, and enhanced the piezoelectric response. In the TME, it synergistically amplified oxidative stress through dual piezocatalytic and enzymatic mechanisms, depleting GSH and alleviating hypoxia to induce PANoptosis. This process was accompanied by the release of ICD markers calreticulin (CRT) and high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), which significantly promoted DC maturation, CD8⁺ T-cell infiltration, and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, ultimately achieving significant tumor suppression and activating a systemic anti-tumor immune response both in vivo and in vitro. These studies all utilize US to activate nanomaterials to generate ROS, induce immunogenic cell death (ICD) (PANoptosis or pyroptosis), and activate anti-tumor immunity. They showcase the synergistic therapeutic effect of piezocatalysis in achieving PANoptosis, providing a new paradigm for piezoelectric nanocatalytic immunotherapy.

Piezo-catalytic immunotherapy. (A) Schematic illustration of US-driven BFTM-induced ROS triggering pyroptosis and amplification of pyroptosis degree through bioorthogonal reaction consumption of fumarate. Adapted with permission from [96], copyright 2025 Wiley. (B) The concrete mechanisms of “outer sono-piezoelectric and inner demethylation regulation” PANoptosis activation. Adapted with permission from [100], copyright 2024 Wiley. (C) Schematic illustration of tumor PANoptosis pathway and immune activation. Adapted with permission from [101], copyright 2024 Wiley-VCH GmbH. (D) A schematic diagram illustrates how piezoelectric catalytic water splitting reduces TIFP and induces apoptosis in CAFs, leading to a reduction in SS and enhanced immune cell infiltration. Adapted with permission from [106], copyright 2025 Published by Elsevier Inc.

Remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment

High tumor interstitial fluid pressure (TIFP) obstructs the infiltration of immune cells. Immune cells cannot effectively move "against" this high pressure to enter the tumor core, leading to the formation of an "immune desert" or an "immune-excluded" microenvironment. Even when T-cells in the peripheral blood are activated by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies, these activated cells cannot enter the "battlefield," resulting in immunotherapy failure [103-105]. Zhang et al. [106] constructed an AgNbO₃/Pt@HA (ANPH) piezoelectric heterojunction system. Under US, the piezocatalytic reaction decomposed water molecules in the tumor interstitial fluid to produce H₂ and ·OH, reducing the TIFP by 48.16%. Simultaneously, the generated ROS induced apoptosis in cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (up to 59.4%), reducing the extracellular matrix (ECM) and solid stress by 44.07%. This significantly promoted the infiltration of CD8⁺ and CD4⁺ T-cells (by 3.95-fold and 3-fold, respectively), successfully converting a "cold tumor" into an immunogenic "hot tumor" (Figure 4D). The mechanism also included the Pt nanozyme-catalyzed decomposition of H₂O₂ to produce oxygen, the promotion of M2-type macrophage polarization to the M1 type, and the induction of ICD. Ultimately, this system suppressed the growth of primary, distant, and metastatic tumors, demonstrating good biocompatibility and systemic anti-tumor immune efficacy.

Secondly, reversing immunosuppression can be achieved by directly modulating the function of key immune cells or the metabolic state of the microenvironment. On one hand, studies have shown that the micro-electric field or related biological effects generated by piezoelectric materials under mechanical stimulation can effectively induce the polarization of pro-tumoral M2-type tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to the anti-tumoral M1 phenotype by activating specific signaling pathways (such as Ca²⁺-mediated pathways) [17]. On the other hand, reprogramming tumor immune metabolism is a more advanced strategy. Lactate accumulation in the TME is a key metabolite causing immunosuppression. Recently, Fan et al. [107] developed an ingenious biohybrid microrobot that utilizes the innate lactate-consuming ability of Veillonella atypica and combines it with the piezocatalytic effect of BTO to accelerate this metabolic process. By efficiently clearing local lactate in the tumor, this system successfully repolarized M2 macrophages to the M1 phenotype, promoted DC maturation, and restored T-cell activity, providing a completely new approach for achieving piezo-immunotherapy through metabolic regulation.