13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(6):3050-3104. doi:10.7150/thno.127402 This issue Cite

Review

Demystifying anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies against pancreatitis and concomitant diseases: a 2025 perspective

1. Department of Gastroenterology, People's Hospital of Longhua Shenzhen, Shenzhen School of Clinical Medicine, Southern Medical University, China.

2. School of Science, Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Advanced Functional Carbon Materials Research and Comprehensive Application, Harbin Institute of Technology, Shenzhen, 518055, China.

3. Department of Gastroenterology, People's Hospital of Longhua, Shenzhen, 518109, China.

Received 2025-10-27; Accepted 2025-11-24; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Pancreatitis is a complex, progressive inflammatory disorder that often transitions from acute to chronic stages, leading to significant comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and bone disorders. These complications complicate treatment strategies, highlighting the need for more targeted approaches. Historically, therapeutic strategies have focused on mechanisms addressing immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, and tissue damage. However, recent advancements have focused on anti-inflammatory mechanisms as primary therapeutic targets for pancreatitis and its associated conditions, as anti-inflammatory treatments help in alleviating chronic inflammation, minimizing tissue damage, and inhibiting disease progression, thereby enhancing recovery and overall patient well-being. This review highlights the most recent advancements in anti-inflammatory therapies for pancreatitis and associated diseases. We discuss how nanotechnology, particularly synthetic and biomimetic nanocarrier-based systems, has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the targeted delivery of anti-inflammatory agents, improving bioavailability and reducing systemic side effects. Importantly, we highlight the potential of gas-based therapies, traditional Chinese medicines, gene therapy, specialty food, living probiotics, exosomes, and even multitargeted approaches to enhance the therapeutic efficacy for pancreatitis and concomitant diseases. Despite these advancements, challenges such as treatment stability, immune response modulation, and scalability have been discussed. Moreover, perspective therapies such as single cell therapy and early diagnosis as treatments have been discussed. This review underscores the need for personalized, multimodal strategies to improve outcomes in pancreatitis management.

Keywords: oxidative stress, nanomedicine, anti-inflammation, Traditional Chinese Medicine, gas therapy, gene therapy

1. Introduction

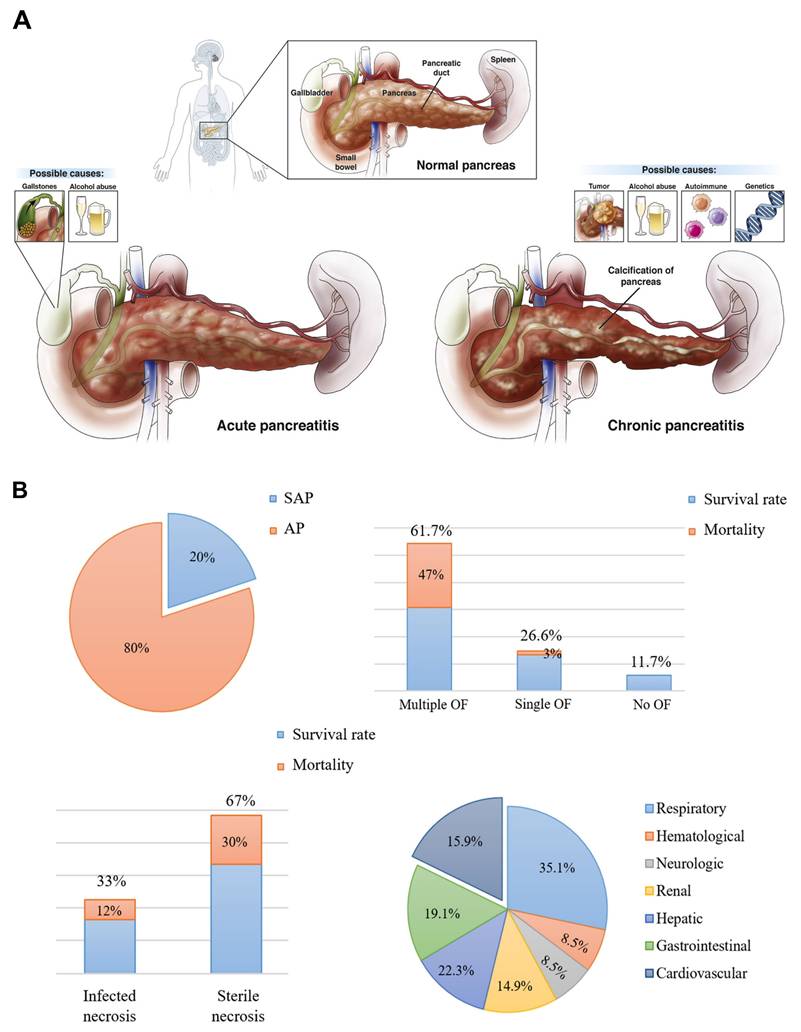

Pancreatitis is a pathological condition primarily triggered by the premature activation of digestive enzymes, particularly trypsinogen, within the pancreas, leading to autodigestion of pancreatic tissues [1]. The condition is generally categorized into two forms: acute pancreatitis (AP) and chronic pancreatitis (CP), which exhibit varying levels of inflammation, hemorrhage, and tissue necrosis that primarily affect the acinar cells and surrounding pancreatic tissues (Scheme 1A) [2]. While significant progress has been made in understanding the pathophysiology of AP, many aspects remain unclear [3]. The condition is associated with numerous etiological factors, such as gallstone-induced biliary obstruction, excessive alcohol consumption, adverse drug reactions, infections, hypercalcemia, genetic predispositions, and autoimmune conditions [4]. In AP, the inappropriate activation of trypsinogen leads to a cascade of enzymatic reactions that cause widespread tissue damage and self-digestion. In cases of mild acute pancreatitis (MAP), the inflammation is typically localized, and organ function is largely preserved. However, severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) involves more widespread inflammation, leading to extensive tissue necrosis, organ failure, and septic complications [5]. Despite advances in intensive care, the mortality rate for SAP remains high, hovering around 30% [6]. Over time, repeated or unresolved inflammation may progress to CP, which is characterized by the replacement of functional pancreatic tissue with fibrotic scar tissue [7]. This fibrotic remodeling leads to the atrophy of ducts and glands, along with calcification and obstruction of the pancreatic ducts [8]. Studies suggest that approximately 20% of AP cases may eventually evolve into CP [9]. CP is marked by persistent inflammation, irreversible fibrosis, and gradual loss of both exocrine and endocrine function [10]. Early detection of CP remains a challenge due to the lack of specific biomarkers, making diagnosis reliant on clinical evaluation, imaging studies, and functional tests [11]. Diagnosis currently relies on a combination of clinical assessment, imaging studies, and pancreatic function evaluations [12]. To date, no disease-modifying therapy has been conclusively established for CP. As a result, treatment is largely palliative, aimed at improving patient quality of life by managing symptoms [13]. This includes lifestyle modifications such as abstaining from alcohol and smoking, use of analgesics including both non-opioid and opioid regimens and surgical interventions in cases with anatomical abnormalities or ductal obstruction [14].

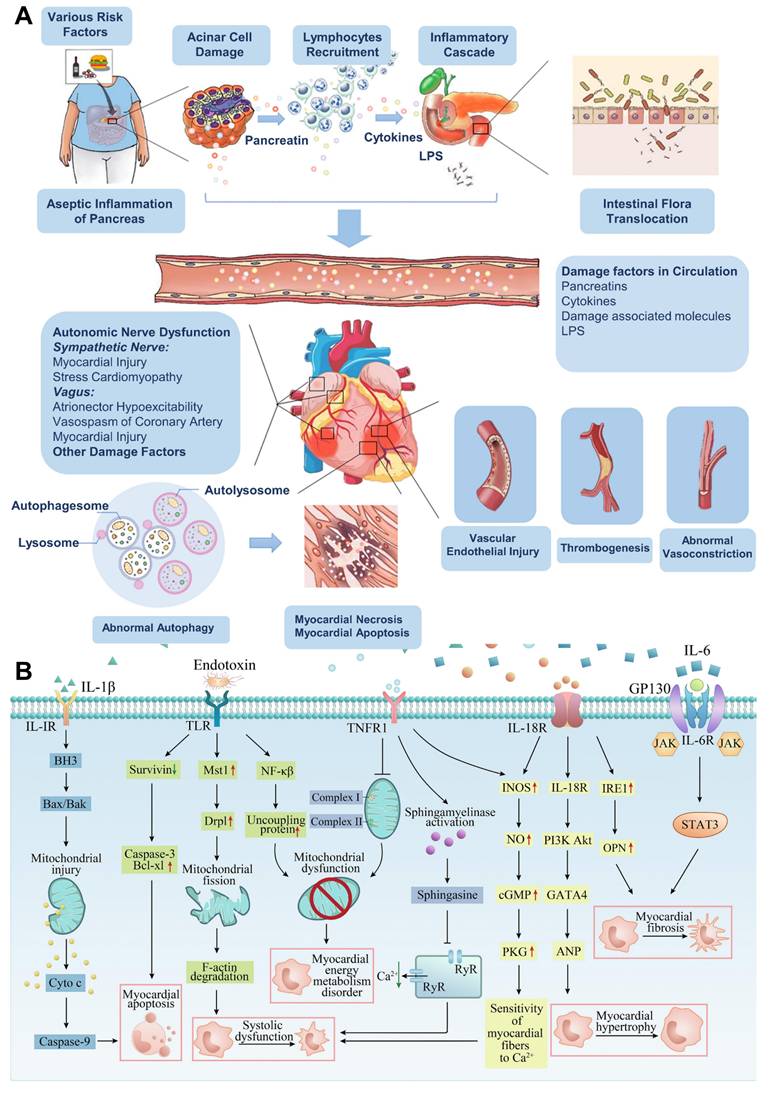

AP is a prevalent gastrointestinal disorder that often necessitates hospital admission. Over recent decades, its global incidence has steadily increased by approximately 3% annually [15]. This upward trend is closely associated with several contributing factors, including excessive alcohol intake, gallstone disease, obesity, and aging populations [16]. Clinically, AP presents along a spectrum of severity ranging from mild and self-limiting to life-threatening forms and is categorized as mild, moderately severe, or severe based on clinical progression and organ involvement [17]. Radiologically, AP is typically classified into two distinct types: acute interstitial pancreatitis and necrotizing pancreatitis [18]. Each exhibit specific morphological patterns and requires different therapeutic strategies [19]. The course and severity of AP are influenced by a complex interplay of genetic factors, environmental exposures, and immune system dynamics (Scheme 1B) [20]. Emerging evidence highlights the significant role of the gut microbiota in shaping immune responses and regulating inflammation throughout the course of AP. Alterations in microbial composition may contribute to disease severity and outcomes, suggesting a potential avenue for therapeutic intervention [21]. This evolving understanding underscores the multifactorial nature of AP and the importance of integrated approaches in its diagnosis, management, and treatment development. Lovett et al. [22] was the first to report in 1971 that AP could lead to cardiac complications, specifically myocardial dysfunction. This condition is marked by impaired myocardial contractility, reduced ejection fraction, diminished responsiveness to fluid resuscitation, a lower peak systolic pressure-to-end-systolic volume ratio, and cardiac enlargement. Subsequent studies investigating systemic organ failure in SAP revealed that approximately 26.6% of patients developed failure in a single organ system. Among these, the respiratory system was most commonly affected (35.1%), followed by the gastrointestinal tract (19.1%), cardiovascular system (22.3%), liver (15.9%), kidneys (14.9%), and both hematological and neurological systems (8.5%). Notably, multiple organ failure (MOF) was observed in 61.7% of cases [23].

Additional research has shown that SAP may be responsible for up to 60.5% of myocardial infarctions (MIs) [24]. Affected individuals frequently present with coexisting cardiac symptoms such as myocarditis, disrupted cardiac output, troponin elevation, arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock, and different MI subtypes [25]. Despite improvements in diagnostics, therapeutic techniques, and imaging, the global burden of AP continues to grow. For instance, AP incidence in the UK has increased substantially from 6.9 to 75 per 100,000 in men and from 11.2 to 48 per 100,000 in women [26]. In the U.S., rates have reached roughly 45 per 100,000 [27]. Managing cardiac injury in the context of AP remains clinically challenging and significantly impacts patient survival. Therefore, reducing mortality hinges on an in-depth, systematic understanding of the mechanisms driving SAP-associated cardiac injury and the development of timely and precise diagnostic strategies [28].

Clinically, numerous landmark trials have addressed critical management problems in AP, such as feeding time and modality, cholecystectomy timing in gallstone-related AP, and infected necrosis therapy. Although current therapies, such as nutritional interventions and surgical procedures, can offer some symptomatic relief, they often fail to tackle the underlying causes of pancreatitis. These conventional approaches manage the disease's effects but do not directly target the complex molecular and cellular pathways driving its progression. Recent advancements in nanomedicine, immune modulation, and precision diagnostics, however, have introduced promising new avenues for more focused and effective treatment.

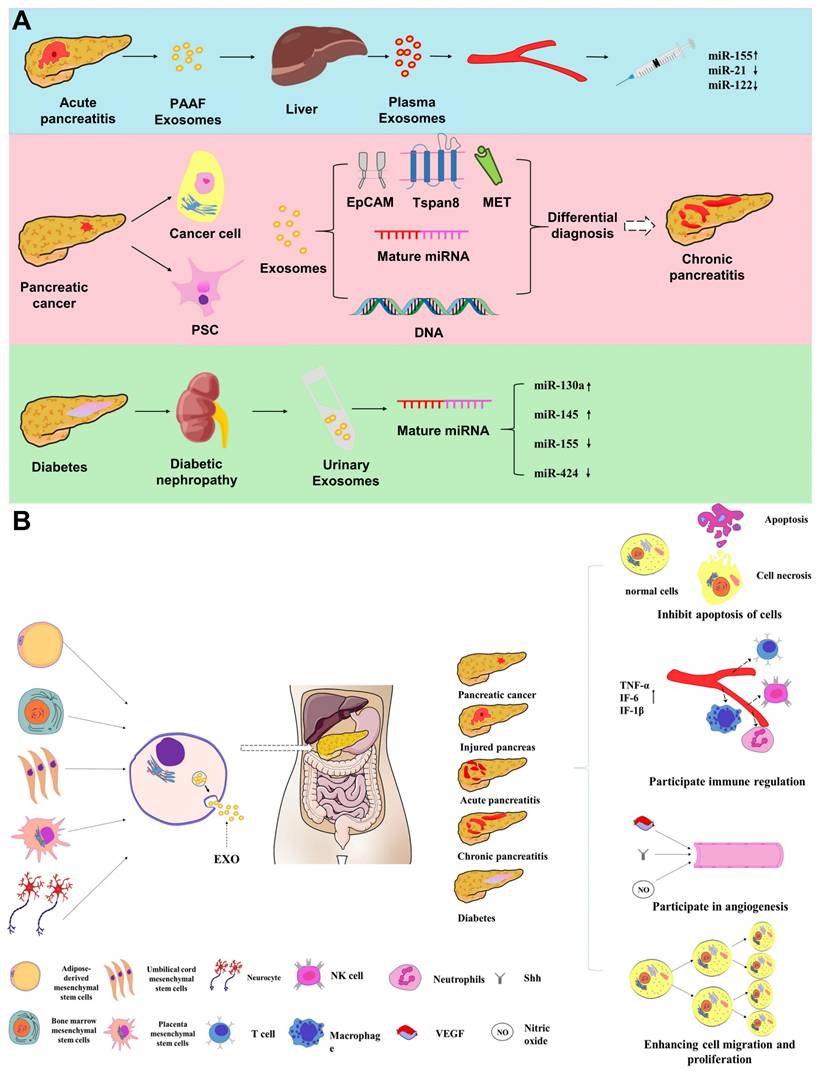

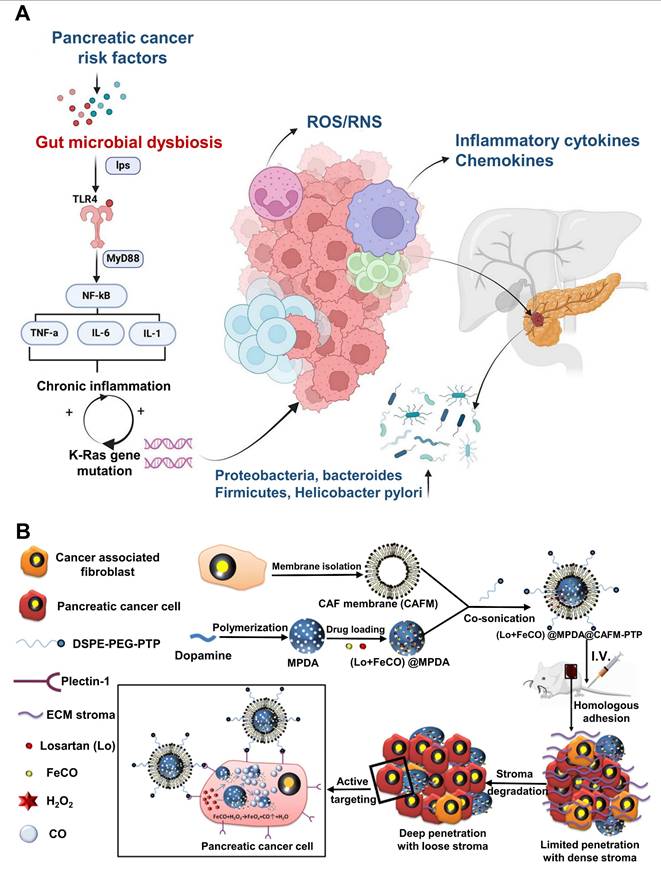

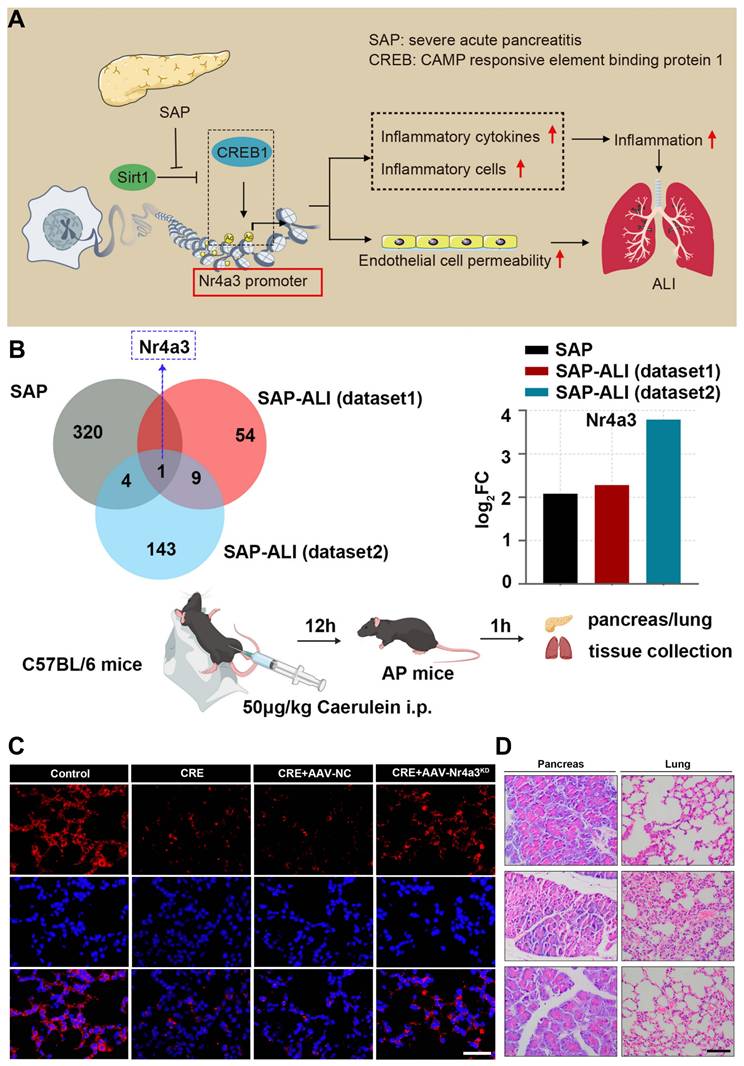

Pancreatitis. (A) Illustration of different types of pancreatitis. (B) Data on acute pancreatitis including the proportion and fatality rates in AP of varying severity, as well as the proportion and mortality rates in AP exacerbated by organ failure. Adapted with permission from ref. [29] Copyrights 2025, Elsevier.

Summary of all types of mechanisms involved in treatment of pancreatitis.

| Mechanism Type | Specific Pathway | Target | Importance | Examples | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-inflammatory | NF-κB Signaling Inhibition | Reduces cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6) and immune activation | Prevents inflammation and tissue damage | Inflixima, Tocilizua, Curcumin | [43] |

| Cytokine Modulation | Suppresses TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β release | Reduces inflammati on, prevents immune storm | Adalimub, Anakinra, Canakinab | [44] | |

| JAK-STAT Inhibition | Blocks cytokine signaling, reduces inflammation | Limits cytokine-driven inflammation | Tofacitin, Ruxolitinb | [45] | |

| NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibition | Decreases IL-1β, IL-18 secretion | Prevents inflammasome-driven injury | MCC950, VX-765 | [46] | |

| Pro-resolving Mediators | Promotes inflammation resolution and tissue repair | Enhances repair, reduces chronic inflammation | Resolvins, Protectins | [47] | |

| Oxidative stress | Antioxidant Activation | Scavenges ROS, reduces oxidative damage | Prevents pancreatic cell injury | N-acetylcysteine, Sulforaphane, Vitamin C | [48] |

| Protease inhibition | Serine Protease Inhibition | Prevents trypsin activation, reduces autodigestion | Prevents premature enzyme activation and pancreatic damage | Gabexate, Nafamostat | [49] |

| Cysteine Protease Inhibition | Inhibits cathepsins, prevents trypsinogen activation | Reduces enzyme-induced pancreatic injury | E64, Cathepsin inhibitors | [50] | |

| Pain modulation | CGRP Antagonism | Reduces neurogenic pain and inflammation | Alleviates pain and reduces inflammation | Telcagepant, CGRP antagonists | [51] |

| Opioid Receptor Modulation | Reduces opioid-induced inflammation and pain | Modulates pain response, reduces opioid side effects | Morphine, Gabapentin | [52] | |

| Immunomodulation | Treg Induction | Expands Tregs, suppresses immune response | Reduces inflammation, prevents fibrosis | IL-2, Rapamycin | [53] |

| M2 Macrophage Polarization | Promotes M2 macrophages, resolves inflammation | Enhances tissue repair and inflammation resolution | IL-4, PPAR-γ agonists | [54] | |

| Fibrosis modulation | Hedgehog Inhibition | Reduces fibrosis, limits collagen deposition | Prevents fibrotic tissue formation | Vismodegib, GDC-0449 | [55] |

| TGF-β Inhibition | Reduces fibrosis, prevents collagen synthesis | Prevents fibrosis, preserves pancreatic function | Fresolimumab, TGF-β monoclonals | [56] |

Recently, in 2023, Liu et al. [30] outlined several potential targets within the inflammatory microenvironment of acute pancreatitis and highlighted opportunities for designing functional nanomaterials against these targets. In 2023 Cai et al. [31] designed biomaterial-based nanoagents, including biodegradable polymers, lipids, or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), to target specific tissues for precise drug delivery and therapeutic effects. In 2025, Coman et al. [32] provided an overview of the latest clinical and experimental findings on the use of antioxidants in AP. In 2025, Zhang et al. [33] summarized the current research trends in nanomedicine for pancreatitis, focusing on both treatment and diagnostic aspects. In 2025, Hong et al. [34] conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (SC-EVs) in the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP), providing valuable evidence for their potential clinical application. In 2025, Michetti et al. [35] discussed the complex role of autophagy in Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and assessed the potential of modulating autophagy as a therapeutic approach. However, none of these reviews delved into integrated therapeutic strategies that address the full spectrum of pancreatitis. In this review, we aim to provide a timely and integrative update that bridges existing knowledge with emerging therapeutic strategies, offering a broader perspective on pancreatitis treatment.

Recent research on pancreatitis has advanced with targeted therapies using synthetic and biomimetic nanocarriers for controlled drug delivery, as well as gene therapies and stem cell-based approaches for reducing inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration [36,37]. However, current advancements have focused on anti-inflammatory mechanisms as primary therapeutic targets for pancreatitis and its associated conditions, as anti-inflammatory treatments help in alleviating chronic inflammation, minimizing tissue damage, and inhibiting disease progression, thereby enhancing recovery and overall patient well-being. In 2021, Akshintala et al. [38] summarized the meta-analysis for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for pancreatitis. In 2022, Zhang et al. [39] discussed the understanding of the pancreas-intestinal barrier axis. In 2023, Halbrook et al. [40] discussed the complexity of the pancreatic tumor microenvironment (TME) and interactions among the numerous cell types within this niche. In 2024, Shi et al. [41] developed an engineered bio-heterojunction with robust ROS-Scavenging and Anti-Inflammation for targeted acute pancreatitis. In 2025, Jiang et al. [42] discussed quercetin's multi-target mechanisms and its advantages over conventional therapies. Since the anti-inflammatory therapy of pancreatitis and concomitant diseases have developed rapidly in the last several years, herein we offer a timely summary. Based on this research development, we have compiled a table (Table 1) that outlines all the mechanistic therapeutic approaches for treating pancreatitis.

This review highlights the most recent advancements in anti-inflammatory therapies for pancreatitis and associated diseases (Scheme 2). We begin with illustration of current pathological understanding of pancreatitis and its progression from acute to chronic stage. Furthermore, we discuss how nanotechnology, particularly synthetic and biomimetic nanocarrier-based systems, has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the targeted delivery of anti-inflammatory agents, improving bioavailability and reducing systemic side effects. Importantly, we highlight the potential of gas-based therapies, traditional Chinese medicines, gene therapy, specialty food, living probiotics, exosomes, and even multitargeted approaches to enhance the therapeutic efficacy for pancreatitis and concomitant diseases. Despite these advancements, challenges such as treatment stability, immune response modulation, and scalability have been discussed. In addition, we present a detailed overview of pancreatitis which outlines the therapeutic paradigms involved in the disease, current therapeutic options, and the potential side effects these treatments may have on other organs. Generally, by integrating the most recent research and therapeutic developments, this review seeks to provide a comprehensive and updated perspective on pancreatitis management, highlighting the need for treatments that target the disease at its core while minimizing off-target effects, ultimately guiding the future of personalized care for pancreatitis patients.

2. Acute to chronic pancreatitis

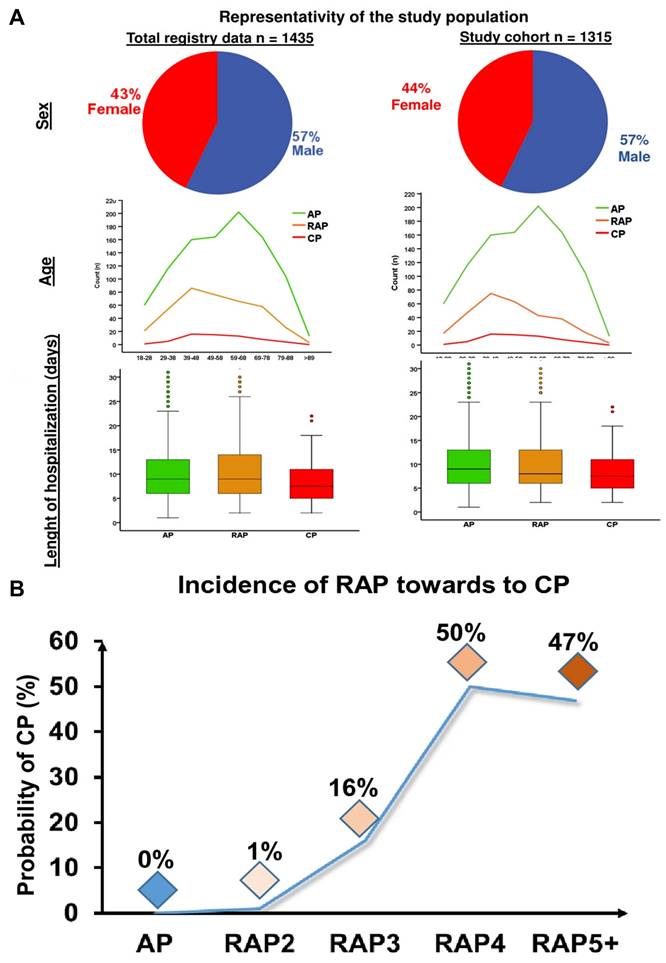

Acute, recurrent acute, and chronic pancreatitis can arise from a variety of causes and are marked by progressive tissue injury, persistent inflammation, fibrosis, scarring, and eventual loss of pancreatic function [57]. While not all individuals who develop CP have a history of initial or repeated acute episodes, acute flare-ups can still occur on a background of established CP [58]. Recurrent episodes of AP may serve as an early warning sign of chronic disease progression. Supporting this, recent findings from the Hungarian Pancreatitis Research Group revealed that nearly half of the individuals who experienced three or more episodes of AP were simultaneously diagnosed with CP, highlighting the clinical importance of early recognition and intervention [59].

Overview of the treatment paradigms for pancreatitis and its concomitant diseases.

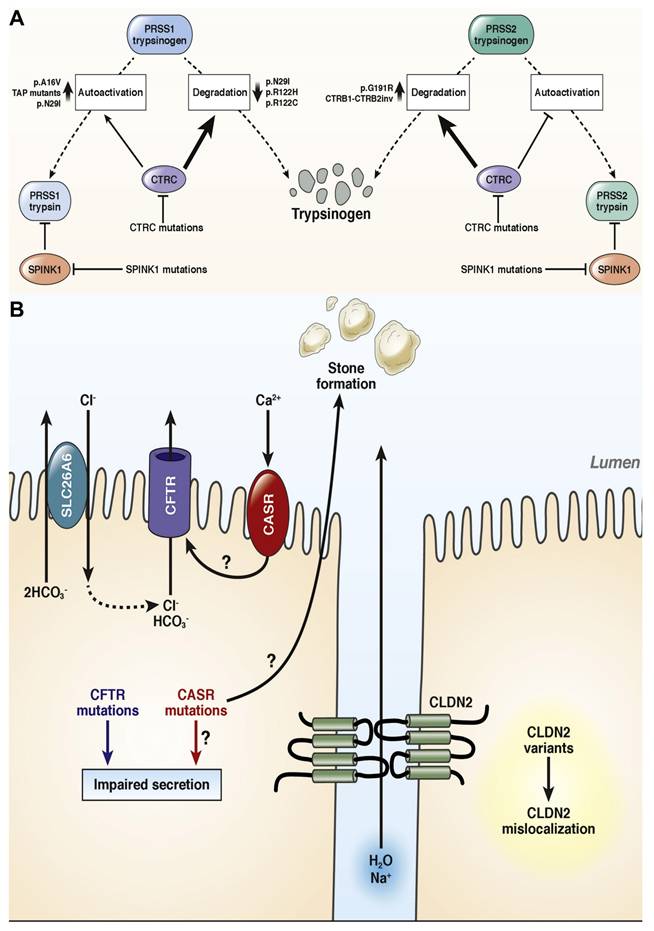

Alcohol remains the most common underlying factor in the progression of pancreatitis, and even moderate consumption has been shown to accelerate pancreatic injury [60]. Other significant contributors include cigarette smoking and elevated triglyceride levels. Hereditary pancreatitis, a rare familial form of chronic pancreatitis, often presents in childhood or adolescence as repeated episodes of acute inflammation [61]. This condition is frequently associated with autosomal dominant mutations in the PRSS1 gene, which encodes cationic trypsinogen particularly the R122H and N29I variants. However, some familial cases occur without identifiable mutations, even when there is a clear inheritance pattern involving multiple affected first- or second-degree relatives across generations. Mutations in several other genes encoding pancreatic enzymes (e.g., CTRC, CPA1, PNLIP, CEL), enzyme inhibitors (like SPINK1), and ion channels (including CFTR and CLDN2) can increase susceptibility to chronic pancreatitis [62]. These genetic variations may lead to increased cellular stress, premature intracellular activation of digestive enzymes, and impaired secretion from acinar or ductal cells, all of which contribute to disease progression [63]. Patients may initially present with a sentinel episode followed by recurrent acute episodes before structural pancreatic changes are detectable by imaging methods such as CT, MRI, or endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or, in infants, by transabdominal ultrasound (TUS). When no obvious environmental trigger (like alcohol or hypertriglyceridemia) is present, the condition may be classified as idiopathic or linked to an underlying genetic mutation [64]. Variants associated with lipid metabolism, such as those seen in type I, IV, or V hyperlipidemia due to mutations in LPL and related genes, can also predispose individuals to acute pancreatitis [65].

The field of pancreatic genetics has evolved rapidly since the initial identification of PRSS1 mutations in hereditary pancreatitis [66]. These discoveries have reinforced the concept of pancreatitis as a disease of autodigestion, driven by early activation of digestive proteases within the pancreas. While this enzymatic activation initiates the condition, the extent and severity are primarily shaped by inflammatory cells that mediate both local damage and systemic immune responses. AP, recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP), and CP are now viewed along a disease continuum. In many cases, chronic alcohol intake or genetic predispositions push a sentinel AP event toward RAP and eventually CP [67].

Interpreting genetic findings in AP can be challenging without long-term follow-up, as some cases may progress to RAP or CP over time [68]. Many of the known pancreatitis-associated genes encode proteins that are highly expressed in the pancreas, including digestive enzymes and their inhibitors [69]. Functional studies have grouped these genetic variants into distinct pathogenic pathways that contribute to the initiation and progression of pancreatitis [70].

The progression from AP to RAP and eventually CP is driven by several critical mechanisms, including the necrosis-fibrosis cascade, cellular senescence, and the activation of pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs). Persistent necrosis leads to chronic inflammation and fibrosis, setting off a cycle of continuous tissue damage and impaired function. Cellular senescence in acinar and ductal cells contributes to this process, as these senescent cells release pro-inflammatory mediators and matrix-degrading enzymes, sustaining the inflammatory environment. In parallel, the activation of PSCs, which transform into myofibroblasts, plays a central role in fibrosis by producing excessive extracellular matrix components. Together, these mechanisms drive the irreversible transition to chronic pancreatitis, extending beyond isolated episodes of inflammation.

Mayerle et al. [71] discussed the development of pancreatitis can follow several distinct mechanistic pathways, including the ductal route, misfolding-dependent processes, and trypsin-dependent mechanisms. One critical trypsin-dependent pathway involves autoactivation, where trypsin itself activates additional trypsinogen molecules. This premature, intra-pancreatic activation can also be initiated by the lysosomal enzyme cathepsin B. To counteract such activation, the pancreas has protective mechanisms, including inhibition of trypsin by the serine protease inhibitor Kazal type 1 (SPINK1) and degradation of trypsinogen by enzymes like chymotrypsin C (CTRC) and cathepsin L. Although CTRC's main role is to promote trypsinogen degradation, it can also enhance activation by modifying the trypsinogen activation peptide into a shorter form that is more easily activated by trypsin (Figure 1A). This delicate regulatory balance can be disrupted by specific trypsinogen mutations that override CTRC's regulatory effects, leading to excessive and pathological trypsin activity within the pancreas. While genetic studies in humans have strongly implicated trypsinogen autoactivation and CTRC-mediated degradation in influencing pancreatic trypsin levels, the roles of cathepsins B and L remain less clearly defined due to a lack of equally robust genetic evidence.

In addition to trypsin-related pathways, ductal dysfunction also contributes to pancreatitis risk, particularly through defects in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). CFTR is a chloride and bicarbonate channel located on the apical surface of epithelial cells (Figure 1B). Mutations affecting CFTR channel function or membrane expression can produce a wide range of clinical manifestations, from asymptomatic carriers to individuals with full-blown cystic fibrosis. Although the overall impact of CFTR variants on chronic pancreatitis (CP) risk is more modest than earlier thought, recent large-scale cohort studies have confirmed that CFTR mutations can still play a pathogenic role. For example, individuals heterozygous for the common p. F508del mutation have a modestly increased risk of CP (odds ratio ~2.5), while the p.R117H variant is associated with an approximate fourfold increase in risk. In cases where individuals carry one severe and one moderate CFTR mutation (compound heterozygotes), the risk of CP is significantly elevated and may be considered causative. However, the contribution of common CFTR polymorphisms, such as T5 or TG12, and bicarbonate-defective CFTR variants that do not cause cystic fibrosis remains a subject of ongoing debate, as most evidence to date does not strongly link them with CP.

AIP is a rare and distinct form of chronic pancreatitis that can present with acute episodes [72]. Initially, before the term "autoimmune pancreatitis" was formally established, it was described by various names, including chronic pancreatitis with hypergammaglobulinemia, lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis with cholangitis, chronic sclerosing pancreatitis, pseudotumorous pancreatitis, duct-narrowing chronic pancreatitis, non-alcoholic duct-destructive chronic pancreatitis, and chronic pancreatitis with autoimmune features [73]. Currently, AIP is classified into two subtypes based on histopathological features. Type 1, also known as lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis, is considered part of the broader IgG4-related disease spectrum. Type 2, often referred to as idiopathic duct-centric pancreatitis, is characterized by granulocytic epithelial lesions. Interestingly, similar lesions have also been identified in children with autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis who show no pancreatic involvement. Type 1 AIP is frequently associated with other manifestations of IgG4-related systemic disease, including sclerosing cholangitis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing sialadenitis, interstitial nephritis, thyroiditis, lymphadenopathy, and interstitial pneumonia [74]. This condition often involves the formation of mass-like lesions in affected organs, along with increased tissue infiltration by IgG4-positive plasma cells or elevated serum IgG4 levels. In contrast, type 2 AIP tends to be more closely associated with inflammatory bowel disease and may carry a less favorable clinical course. From an epidemiological and clinical outcome standpoint, it is well established that with each successive episode of AP, patients may progress closer to developing CP [75]. Therefore, analyzing biomarkers collected during AP episodes, regardless of their direct association with the pancreas, could prove valuable in identifying early-stage chronic pancreatitis (ECP). The next section of this study focuses on exploring these diagnostic possibilities [76,77].

Hegyi et al. [78] performed a comprehensive analysis on a total of 102 biomarkers, with the primary findings summarized in Figure 2A. The study also assessed whether an increased number of acute inflammation episodes correlates with a heightened risk of developing (CP). Results showed that individuals with only one or two AP episodes had less than a 1% chance of progressing to CP. However, the likelihood rose significantly with repeated episodes those who experienced three AP events had a 16% risk, while those with four or more episodes faced a 50% chance of developing CP. These data suggest that experiencing three or more acute pancreatitis episodes should be considered a strong predictive factor for the future development of chronic pancreatitis (Figure 2B).

3. Nanomedicines for pancreatitis therapy

3.1 Nanomedicines vs free drugs

Nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems provide an effective solution to the challenges posed by traditional free drugs, such as limited bioavailability and non-specific distribution [79]. These systems, which include synthetic carriers like lipid nanoparticles, liposomes, and polymeric nanoparticles, as well as biomimetic options like biomacromolecule-based nanoparticles and extracellular vesicles, significantly enhance drug stability, solubility, and targeted delivery [80]. By functionalizing nanocarriers with specific targeting agents, drugs can be directed to precise sites of action, improving therapeutic outcomes while minimizing side effects [81]. Additionally, nanocarriers enable controlled and sustained drug release, reducing the need for frequent dosing and enhancing patient adherence, while also decreasing systemic toxicity by ensuring localized drug delivery. This makes nanomedicines a powerful and adaptable approach in modern drug therapy [82].

(A) Genetic risk factors linked to the pathogenic pathway that is dependent on trypsin. (B) Risk factors linked to genetics and the ductal pathologic route. Adapted with permission from ref. [71] Copyrights 2019, Elsevier.

Nanomedicine represents a cutting-edge approach in drug delivery, offering several key advantages over traditional small-molecule drugs [83]. These include the ability to deliver treatments directly to diseased tissues, release therapeutic agents in a controlled manner over time, minimize off-target toxicity, and improve overall drug safety. Such capabilities are especially beneficial in treating pancreatitis, where inflammation is localized and conventional treatments often cause systemic side effects [84]. In recent years, various nanoparticle-based systems have been investigated for their ability to target the pancreas more effectively, regulate oxidative stress, and modulate inflammatory pathways [85]. These include biomimetic nanoparticles cloaked in immune cell membranes, antioxidant-loaded carriers, and nanoscale materials that mimic the activity of protective enzymes. Preclinical studies have shown that these nanoformulations can enhance drug efficacy and reduce complications, making them promising tools for the future of pancreatitis therapy [86].

(A) representativeness of the population under investigation. (B) Development of CP following recurring occurrences (RAP) following the initial AP event. Adapted with permission from ref. [78] Copyrights 2021, Springer Nature.

Cerium-based nanomedicines represent an emerging class of therapeutic agents with considerable potential in treating a variety of diseases, particularly those involving oxidative stress and inflammation. Cerium, a rare earth metal with unique redox properties, can exist in both its trivalent (Ce+3) and tetravalent (Ce+4) states, making it highly effective in modulating ROS and restoring cellular balance. When engineered into nanoparticles, cerium compounds can harness these properties to deliver targeted therapeutic effects with high specificity, making them an ideal candidate for the treatment of conditions such as pancreatitis, cancer, and neurodegenerative diseases. By exploiting the dual functionality of cerium nanoparticles acting as both antioxidants and calcium stabilizers novel nanomedicines can address the complex cellular disruptions associated with disease progression, offering promising avenues for innovative and effective treatments [87].

AP arises from multiple causes and is characterized by inflammation of the pancreas. During this inflammatory process, the pancreatic environment becomes rich in ROS, inflammatory cells, enzymes, protons (H+), and other bioactive molecules, all of which contribute to the progression of AP through various mechanisms [88]. Recently, several nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems and nanomedicines have been developed to leverage this inflammatory microenvironment, improving both the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory conditions such as AP [89]. This approach utilizes specific markers within the inflamed tissue to enhance therapeutic precision. Targeting these sites can be achieved either passively or actively [90]. Passive targeting exploits abnormal biochemical features of the inflamed pancreas such as altered pH levels, elevated ROS, and increased enzyme activity as well as the enhanced permeability of the tissue, allowing drugs to accumulate more effectively [91]. Active targeting, on the other hand, involves designing delivery systems that specifically bind to receptors that are overexpressed in the inflamed pancreatic tissue, thereby directing treatment precisely to the affected area and improving therapeutic outcomes [92,93].

3.2 Synthetic nanocarriers

3.2.1 Solid lipid and polymer-based nanoparticles

Lipid and polymeric nanoparticles are among the most thoroughly studied materials in nanomedicine. It is therefore unsurprising that these types of nanocarriers have also been utilized in the treatment of pancreatitis [94]. For instance, Cervin et al. [95] encapsulated somatostatin, a peptide hormone used in pancreatitis treatment within lipid liquid crystal materials to improve its clinical effectiveness. This nano-formulation extends the peptide's half-life from just a few minutes to about an hour. Additionally, polymeric nanoparticles within a carefully controlled size range can exploit the ELVIS (Enhanced Lipid Vehicle-Induced Selectivity) effect extravasation through leaky blood vessels followed by capture by inflammatory cells. This phenomenon enables passive targeting of nanoparticles to inflamed tissues, reducing systemic side effects. Increasingly, researchers are leveraging the ELVIS effect for drug delivery in inflammatory conditions, including pancreatitis, to enhance targeted therapy. The ELVIS effect is highly dependent on the specific model of AP, and its effectiveness can differ across various experimental setups. This passive targeting approach capitalizes on the changes in vascular permeability and increased blood flow that occur during inflammation, which may vary in different AP models. In models like cerulein-induced AP, the inflammatory response often leads to greater vascular permeability, allowing for enhanced accumulation of nanoparticles in the affected tissue. However, in other models, such as bile duct ligation-induced AP, changes in the microvascular structure, along with the development of fibrosis, can hinder the efficacy of passive targeting strategies, reducing nanoparticle uptake in the pancreas. Additionally, factors like the duration of the disease, the severity of the inflammatory response, and the immune environment in each model play a critical role in the success of passive targeting approaches, further influencing their overall effectiveness [96].

Yang et al. [97] developed poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) PLGA nanoparticles (CQ/pDNA/PLGA NPs) co-loaded with plasmid DNA (pDNA) and chloroquine diphosphate (CQ). In this approach, pDNA was compacted by CQ before being encapsulated within the PLGA nanoparticles. This formulation not only enhanced transfection efficiency but also improved targeting to CT26 transplanted tumors. More importantly, in a mouse model of L-arginine-induced acute pancreatitis (AP), these CQ/pDNA/PLGA nanoparticles showed remarkable targeting capabilities. Building on this work, the same team later introduced tamoxifen-loaded PLGA nanoparticles (TAM-NPs) combined with CQ-loaded liposomes (CQ-LPs). This combined treatment alleviated AP and severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) by modulating IDO signaling pathways in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. These studies highlight how PLGA nanoparticles exploit the ELVIS effect, facilitating their uptake by neutrophils and pancreatic macrophages, which in turn enables efficient drug delivery and therapeutic benefit in AP. This macrophage-targeting property of PLGA nanoparticles has also been utilized for precision therapies in pancreatic cancer.

3.2.2 Inorganic-based nanoparticles

Treatment of inflammatory diseases often involves the use of exogenous agents that mimic natural enzymes and exhibit antioxidant properties. Inorganic nanoparticles, compared to polymer or lipid-based ones, typically offer a more uniform size distribution and smaller particle sizes [98]. Their surface characteristics also make them particularly suitable for attaching ligands. As a result, synthetic enzymes stand out as highly effective tools for restoring imbalanced redox homeostasis [99]. According to Hu et al. [100] polyvinylpyrrolidone-stabilized molybdenum diselenide nanoparticles (MoSe2-PVP NPs) were easily synthesized and demonstrated efficient enzyme-mimicking properties, capable of scavenging free radicals such as 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and superoxide anions (•O2-). In animal models of acute pancreatitis (AP), MoSe2-PVP NPs showed significant protective effects and notably improved cell survival under oxidative stress induced by H2O2. Similarly, Prussian blue, a traditional dye historically used to treat thallium and radioactive element poisoning, has been engineered into nanoparticles (PB NPs) with remarkable physical, chemical, optical, and magnetic properties, along with high chemical stability. Recently, PB NPs have attracted attention due to their ability to mimic various antioxidant enzymes, making them promising candidates for treating inflammatory diseases.

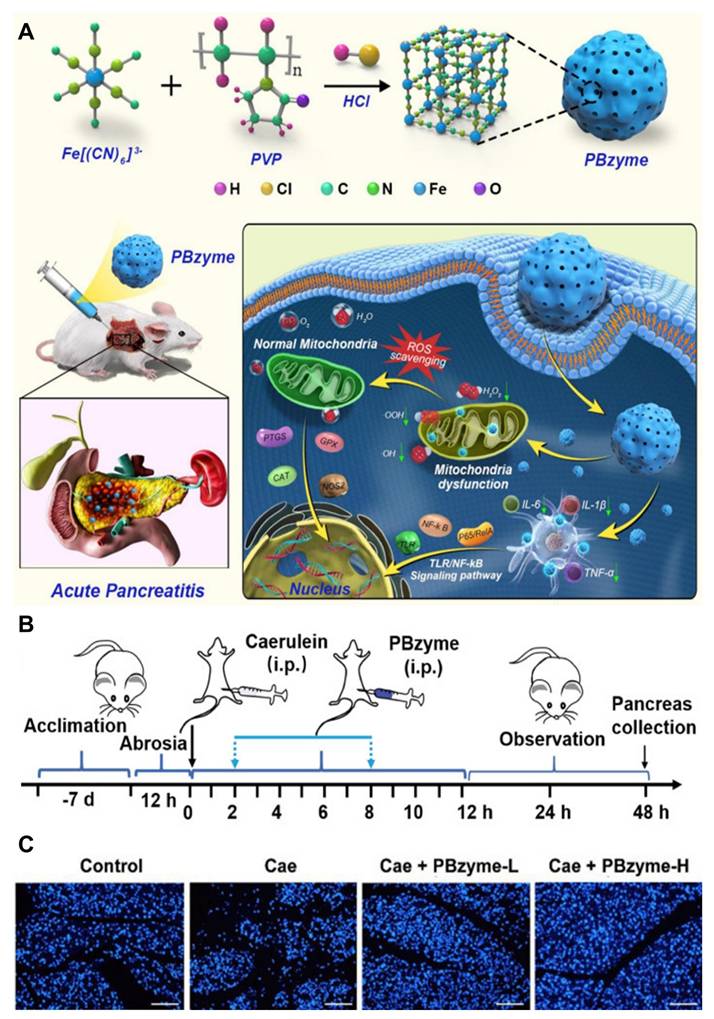

Zheng et al. [101] developed prussian blue nanoparticles (PBzyme) that act as nano-enzymes capable of neutralizing various reactive oxygen species (ROS) and pro-inflammatory molecules such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), hydroperoxyl radicals (•OOH), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), as illustrated in (Figure 3A). PBzyme reduces oxidative damage, including lipid peroxidation, necrosis, and nucleic acid injury, by inhibiting the Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated NF-κB signaling pathway. The preventive effects of PBzyme were evaluated in vivo using the caerulein-induced AP mouse model, which is widely used due to its ease of induction, non-invasiveness, reproducibility, and histological similarity to human AP. Treatment with PBzyme, especially at higher doses (Caerulein + PBzyme-H group), led to decreased serum amylase (AMS) and lipase (LPS) levels compared to untreated AP mice (Figure 3B). Apoptosis in pancreatic tissues, assessed by TUNEL staining, was elevated in the caerulein-only group but significantly reduced in mice treated with both low and high doses of PBzyme (Figure 3C). The therapeutic action of PBzyme in preventing AP appears to involve its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. By scavenging ROS and suppressing the TLR/NF-κB pathway associated with inflammation and oxidative stress, PBzyme enhances the body's natural defense mechanisms, resulting in effective prevention of AP. Besides targeting TLR/NF-κB signaling, PBzyme's mechanism aligns with several established pharmacological approaches for managing AP. Compared to current AP medications, PBzyme offers advantages such as straightforward synthesis and stable in vitro preservation. Moreover, the production process has been optimized to allow gram-scale synthesis of uniform PBzyme nanoparticles.

Given its simple composition, scalable manufacturing, inherent bioactivity, biosafety, and significant preventive efficacy, PBzyme presents a promising candidate for AP prevention. Future studies using non-human primate models are necessary to further elucidate PBzyme's mechanisms, assess long-term safety, and confirm its preventive benefits. These findings provide a foundation for the clinical development of PBzyme for AP and potentially other ROS- and inflammation-related diseases.

Apart from the metallic inorganic nanoparticles discussed above, selenium-based non-metallic inorganic nanoparticles can also be used to alleviate pancreatitis. Abdel-Hakeem et al. [102] utilized antioxidant-rich selenium nanoparticles, sized between 10 and 45 nm, to help restore both endocrine and exocrine functions in the pancreas of mice with AP. Meanwhile, non-metallic nanoparticles like porous silica are known for their excellent drug-loading capacity. Although chitosan oligosaccharides (COS) possess antioxidant properties, their widespread, non-targeted distribution in the body limits their effectiveness in producing significant therapeutic outcomes in vivo. Zeng et al. [103] loaded chitosan oligosaccharides (COS) into porous SiO2 materials to create a complex (COS@SiO2) that releases COS gradually in response to acidosis caused by SAP in pancreatic tissues. In SAP mouse models, the controlled release of COS effectively reduced systemic inflammation and oxidative stress markers, inhibited the expression of NF-κB and the NLRP3 inflammasome by activating the Nrf2 pathway, and ultimately lessened pancreatic and secondary lung tissue damage. However, it has also been reported that intravenous administration of commonly used inorganic nanoparticles may promote tumor formation by facilitating the spread of breast cancer cells, which raises concerns about their safety and limits their use in medical applications [104,105].

(A) Diagrammatic representation of the therapeutic mechanism of PBzyme, which prevents acute pancreatitis by preventing the activation of the TLRs/NF-κB signaling pathway linked to oxidative stress and inflammation. (B) PBzyme pretreatment for AP: overall experimental protocol by blocking the production of inflammatory factors in vivo. (C) Assessment of pancreatic apoptosis with TUNEL fluorescent staining (Scale bar: 100 μm). Adapted with permission from ref. [101] Copyrights 2021, IVYSPRING.

3.2.3 Mesoporous organosilica nanocarriers

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) have attracted significant interest due to the rapid development of mesoporous materials. These nanoparticles offer unique advantages, including a high surface area, tunable pore sizes, remarkable stability, and a diverse range of framework compositions [106]. Over the years, a variety of silica-based agents for diagnostic and therapeutic applications have been developed, benefiting from their recognition as safe by the FDA. However, MSNs face challenges such as cumulative toxicity and concerns regarding their long-term safety. These issues stem from the stable Si-O-Si framework of MSNs and their limited ability to degrade in biological systems [107].

To address these concerns, efforts have focused on improving the biodegradability and biosafety of MSNs without compromising their advantageous physicochemical properties. One promising approach is the hybridization of MSNs with organic components, which enhances their biocompatibility [108]. Mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles (MONs) are formed by incorporating organic groups into the silica structure at a molecular level using sol-gel processes. This integration is achieved by utilizing bissilylated organosilica precursors along with structure-directing agents (SDAs). Additionally, selective etching methods can be employed to produce hollow mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles (HMONs), which possess a considerable amount of internal void space [109]. This hollow architecture and the unique organic/inorganic hybrid silsesquioxane framework of HMONs enable them to overcome limitations inherent in conventional MSNs, such as suboptimal drug loading capacity and poor degradation rates. Furthermore, HMONs can be tailored with advanced functionalities, such as multimodal imaging capabilities and stimuli-responsive degradation, by carefully selecting appropriate organosilica precursors [110]. These modifications make HMONs highly versatile and promising for biomedical applications. The size of nanoparticles plays a crucial role in their biological behavior and effectiveness in theranostic applications. Nanoparticles smaller than 50 nm are capable of penetrating deeper tissues and circulating in the bloodstream for extended periods. Recent studies have focused on HMONs in the size range of 50-200 nm, though sub-50 nm HMONs have shown enhanced tumor accumulation, prolonged blood circulation, and reduced risk of vascular occlusion [111]. These characteristics lead to better-targeted delivery, improved biocompatibility, and overall enhanced therapeutic efficacy [112].

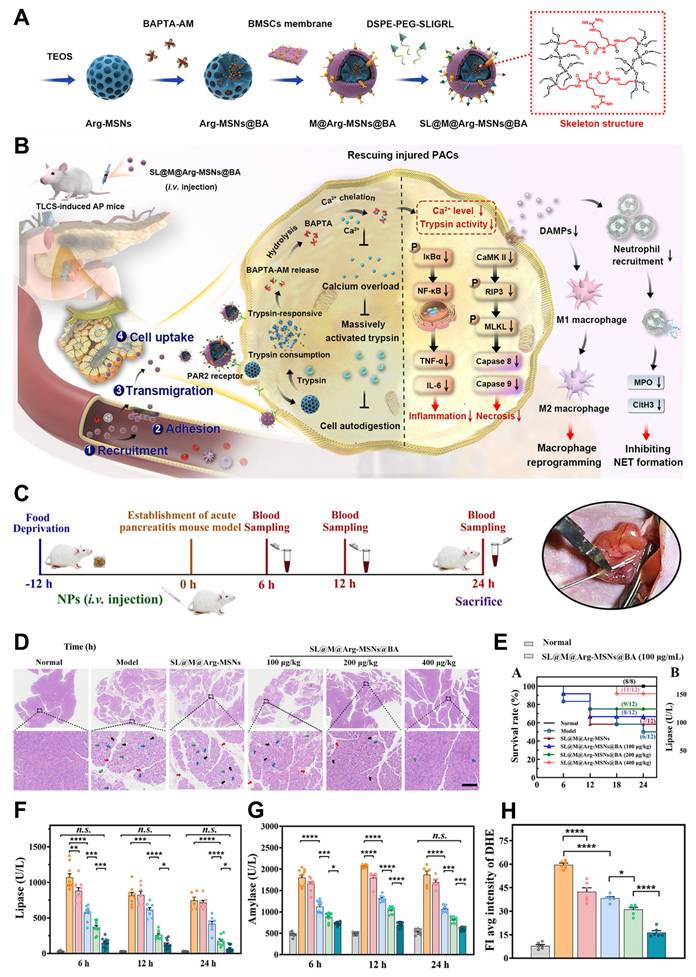

Huang et al. [113] have provided a comprehensive review of the synthesis methods and the latest advancements in sub-50 nm HMONs for theranostic applications. Wang et al. [114] developed an organosilica precursor incorporating an arginine-based amide bond, which can be cleaved by trypsin. This precursor was incorporated into the mesoporous silica framework to form trypsin-responsive organo-bridged mesoporous silica nanoparticles (Arg-MSNs@BA). These nanoparticles were designed to encapsulate 1,2-bis (2-aminophenoxy) ethane-N,N,N,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA-AM, BA), a membrane-permeable calcium chelator, to achieve controlled release of the drug and rapidly eliminate excess intracellular calcium during the early stages of AP (Figure 4A-B). To enhance the specificity and targeting ability of the nanoparticles, the Arg-MSNs@BA were further functionalized with a cell membrane derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs), creating SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA. This functionalization was designed to promote precise targeting of injured cells, immune evasion, adhesion to inflammatory endothelial cells, and migration across the endothelial barrier. Additionally, a PACs-targeting peptide (SLIGRL, SL) was introduced to the membrane, which binds to protease-activated receptor-2 (PAR2), predominantly expressed on the apical surface of PACs. As a result, the membrane-camouflaged nanoparticles are able to specifically migrate towards and adhere to the inflamed endothelium, allowing for targeted delivery to PACs. Upon internalization by PACs, the core Arg-MSNs@BA degrade rapidly in response to excessive trypsin activation. This degradation process releases the encapsulated BAPTA-AM (BA), which chelates the excess Ca2+ ions inside the cells. By regulating intracellular calcium homeostasis and restoring the cell's redox balance, this mechanism helps to mitigate the cascade of apoptosis and necrosis, rebalance the inflammatory microenvironment, reduce pancreatic tissue damage, and prevent damage to distant organs. Moreover, the trypsin-responsive feature of the Arg-MSNs also inhibits acinar cell autodigestion, further preventing damage to pancreatic cells.

The synergistic combination of trypsin inhibition and calcium chelation, facilitated by the biomimetic membrane, provides a comprehensive and multidimensional therapeutic approach for AP. This innovative strategy holds significant promise for enhancing AP treatment by targeting both the symptoms and the underlying causes of the disease. A treatment schedule and a snapshot of the modeling process are illustrated in (Figure 4C). One hour after intravenous administration, both DiR-loaded M@Arg-MSNs and SL@M@Arg-MSNs preferentially accumulated in pancreatic tissues, as evidenced by a strong fluorescence signal in the pancreas. Histopathological analysis revealed that while severe injury was observed in the pancreatic tissues of AP mice, administration of SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA at doses of 100 and 200 μg·kg⁻¹ led to reduced lobular space widening, decreased acinar necrosis, less inflammatory cell infiltration, and moderate effects on pancreatic edema (Figure 4D). Treatment with SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA significantly lowered the TCLS-induced mortality rate in a dose-dependent manner, as shown in (Figure 4E). Specifically, at a BA dosage of 400 μg·kg-1, the survival rate of AP mice dramatically improved from 50.0% to 91.6% after a single dose. Interestingly, increasing the BA dosage beyond this point did not result in further improvement of pancreatic damage or survival rates, which aligns with previous studies suggesting an optimal therapeutic dosage range.

Regarding typical biomarkers for AP, such as lipase and amylase, significant elevation was observed shortly after the TCLS insult, with increases of 36.0 and 3.8 times, respectively, at the 6-hour mark. These elevated levels remained high at 24 hours (Figure 4F-G). After 6 hours of treatment with blank SL@M@Arg-MSNs, lipase levels were reduced by 17.5%, while amylase levels decreased by 13.2% at the 12-hour time point. This therapeutic effect is likely due to the degradation of the Arg-MSNs backbone, which results in the competitive inhibition of excessive trypsin activation. Additionally, the SL peptide, which acts as a receptor agonist, binds to PAR2 receptors, contributing to a reduction in pancreatitis severity. Notably, the group treated with a single dose of SL@M@Arg-MSNs@BA at a BA dosage of 100 μg·kg-1 showed significant suppression of oxidative stress, evidenced by a 35.8% reduction in superoxide levels, as indicated by DHE fluorescence intensity, when compared to the AP model group (Figures 4H).

By controlling ion homeostasis and inhibiting trypsin activity, our biomimetic trypsin-responsive nanocarrier rapidly and precisely reverses PAC damage at the earliest stages of cell injury, halting the pathophysiological progression of AP and offering significant therapeutic translation potential.

3.2.4 Liposome, micelles and dendrimers

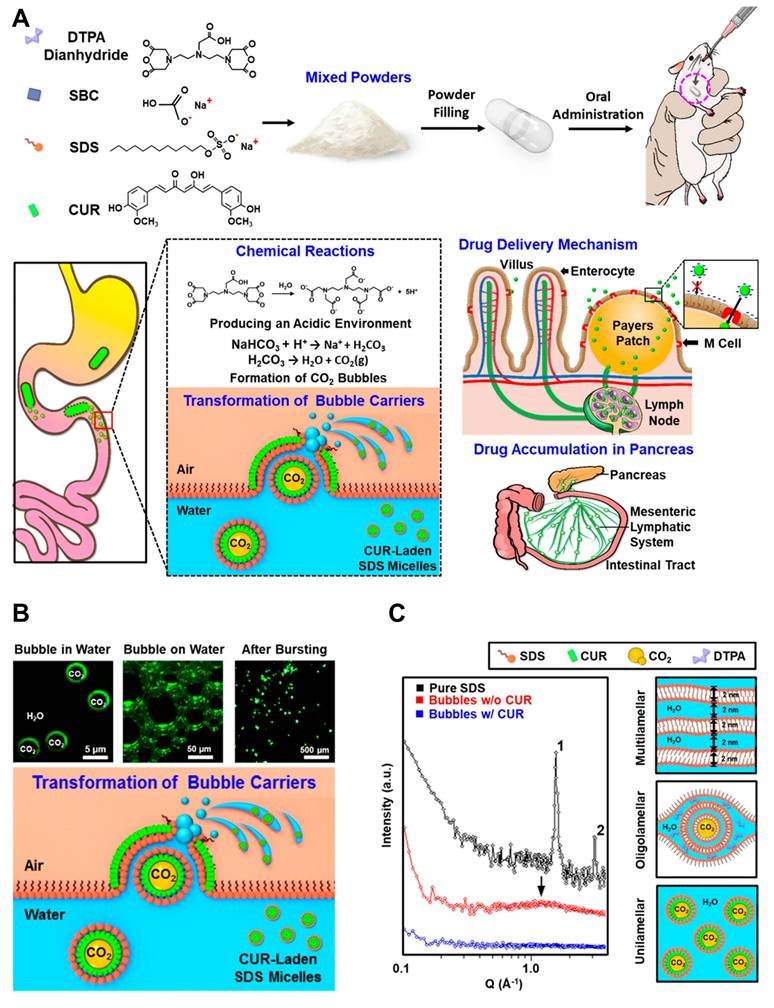

Dendrimers, liposomes, and micelles have also been described as innovative drug delivery systems for the management of pancreatitis [115]. The research team led by Hsing-wen Sung created a nanocarrier system (TLNS) that resembles a transformer. The ability of TLNS to undergo structural alterations in the intestinal environment and form nanoscale micelles with curcumin (CUR) has been verified in vitro [116]. Figure 5A [117] depicts the AP-targeted treatment approach using curcumin (CUR)-loaded micelles. In rats treated with TLNS, the pancreas showed nearly a 12-fold increase in CUR signal compared to those given free CUR, suggesting enhanced recovery from acute pancreatitis. These results indicate that TLNS significantly boosts the gut's capacity to absorb drugs, potentially making oral administration a more effective strategy for treating pancreatitis.

The bubble carriers' shells were composed of monolayers of fluorescent curcumin (CUR), as illustrated in (Figure 5B). A significant portion of these fluorescent bubbles eventually reached the water/air interface. Under microscopic observation, the nano-assemblies exhibited a double-layer fluorescence pattern. The proposed TLNS system, which delivers the drug in the form of nano-emulsions, was developed to significantly enhance the oral bioavailability of poorly water-soluble drugs. Structural changes in this TLNS were analyzed using fluorescence microscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). As depicted schematically in the right panel of (Figure 5C), the SAXS pattern of powdered sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) displayed two distinct peaks with a 1:2 position ratio upon hydration, indicating the surfactant molecules self-assemble into a multilamellar structure. This structure alternates between lipophilic layers (formed by two sublayers of alkyl chains) and hydrophilic layers (composed of head groups and water molecules). Literature suggests that intestinal M cells can be passively targeted by the CUR-loaded SDS micelle nano-emulsions derived from TLNS. These nano-emulsions can then be transported via the mesenteric lymphatic system to accumulate in pancreatic tissue, effectively reducing acute pancreatitis (AP) severity. This TLNS approach offers a promising strategy to efficiently emulsify a broad range of poorly water-soluble drugs within the gastrointestinal tract, improving their solubility and significantly enhancing oral bioavailability.

Additionally, dendrimers bearing polyhydroxyl groups have shown antioxidant properties, suggesting potential use in pancreatitis treatment. Two generation 5 (G5) polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers, G4.5-COOH and G5-OH, containing carboxyl and hydroxyl groups respectively, were synthesized as previously described. Their protective effects were evaluated in a caerulein-induced AP mouse model. Both dendrimers notably reduced inflammatory responses in AP mice and significantly inhibited LPS-induced inflammatory macrophage production in mouse peritoneal cells. They also caused a marked reduction in monocytes and white blood cells. Between the two, G4.5-COOH demonstrated a stronger protective effect in vivo against AP than G5-OH. Finally, the researchers proposed that these dendrimers reduce inflammation by suppressing NF-κB nuclear translocation in macrophages.

(A) Diagrammatic Representation and SL@Arg-MSNs@BA Preparation. (B) Treatment Mechanism in a Mouse Model of Acute Pancreatitis Caused by Retrograde Infusion of Sodium Taurocholate. (C) Experimental therapy process flowchart. (D) Pancreatic H&E staining. (E) AP mice's survival rate following various treatments. (F) The levels of serum lipase (G) and amylase. (H) semiquantitative findings regarding its mean fluorescence intensity. Adapted with permission from ref. [114] Copyrights 2024, American Chemical Society.

(A) Mechanism of CUR-loaded SDS micelle nanoemulsion creation comes from the suggested TLNS that self-assembles in the gastrointestinal tract. (B) Fluorescence microscopy of CUR-loaded SDS micelle nanoemulsions. (C) CUR-loaded SDS micelle nanoemulsions for X-ray solution scattering (SAXS). Adapted with permission from ref. [117] Copyrights 2018, American Chemical Society.

Each synthetic nanocarrier Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs), Poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), inorganic nanoparticles, and mesoporous silica offers unique advantages and challenges for drug delivery applications. SLNs and PLGA are well-regarded for their excellent drug loading capacities and biocompatibility. PLGA stands out for its biodegradability and ability to provide controlled release, though both rely primarily on passive targeting mechanisms, which limits their precision. On the other hand, inorganic nanoparticles stand out for their high targeting efficiency, enabled by surface modifications that allow for targeted delivery, particularly in cancer therapies. However, issues regarding their biosafety and biodegradability persist, which may hinder their widespread use. Mesoporous silica also offers significant drug loading capabilities due to its high surface area and customizable pore structure, and it can be modified for targeted delivery [118]. Yet, its degradation rate and long-term safety are areas that require further refinement. While SLNs and PLGA have seen more clinical success due to their well-established safety profiles, inorganic nanoparticles and mesoporous silica hold great promise for more advanced, targeted therapies. The selection of a nanocarrier ultimately depends on the specific therapeutic needs, with considerations for factors such as targeting precision, drug release control, and overall safety.

3.3 Biomimetic nanocarriers

3.3.1 Biomacromolecule-based nanoparticles

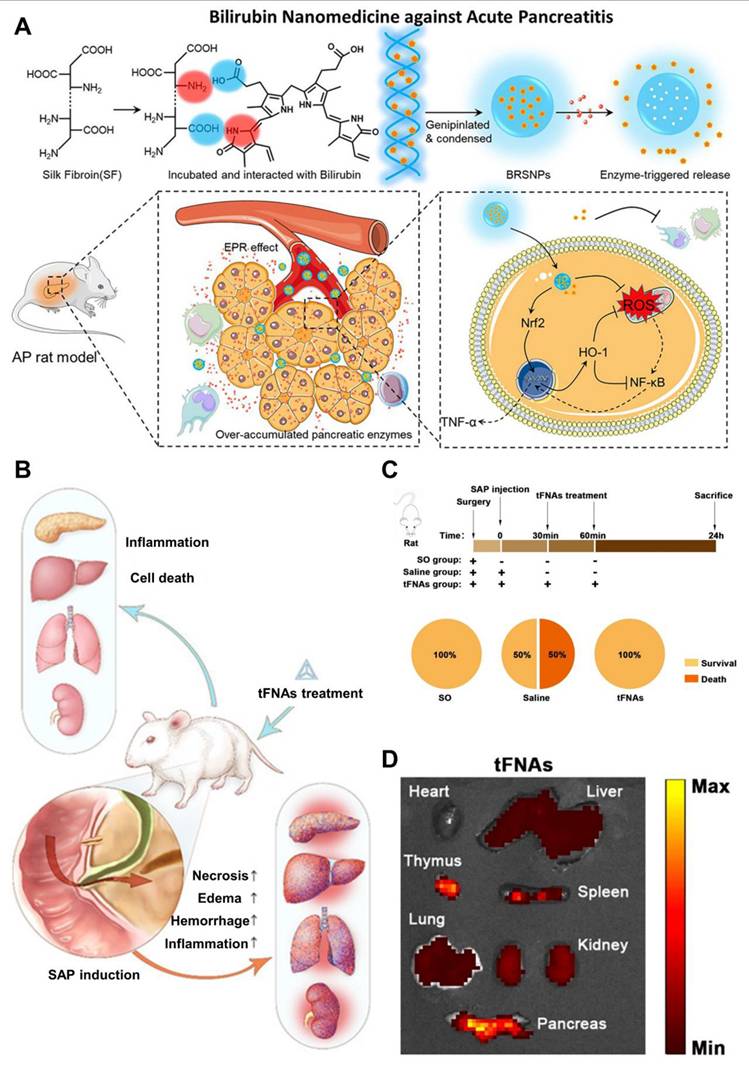

Biological macromolecules like proteins and nucleic acids provide distinct advantages in biocompatibility and safety compared to synthetic polymers and artificial lipids [119]. Additionally, certain proteins have shown responsiveness to the elevated levels of enzymes such as amylase, protease, and lipases found in pancreatitis-affected tissues [120]. This property allows them to be used as smart drug carriers that enable effective passive targeting of pancreatitis lesions. Yao et al.[121] utilized silk fibroin as a carrier to construct a primary three-dimensional (3D) structure resembling the DNA double helix that incorporated bilirubin, which then collapsed into nanoparticles. In vivo imaging studies showed that these bilirubin-loaded silk fibroin nanoparticles (BRSNPs) accumulated more efficiently in pancreatic tissue, enabling passive targeting. In both acinar cell models and L-arginine-induced AP rat models, BRSNPs released bilirubin in response to elevated pancreatic enzymes, such as trypsin, at the AP site (Figure 6A). Bilirubin effectively reduced mitochondrial ROS production, activated the Nrf2 signaling pathway, increased HO-1 expression, and inhibited the pro-inflammatory NF-κB pathway. Treatment with BRSNPs significantly lowered various blood biomarkers, including amylase, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen. Additionally, it alleviated oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation in pancreatic cells, prevented edema and fibrosis, and showed superior therapeutic effects against AP compared to somatostatin or free bilirubin treatments. Beyond proteins, nucleic acids also serve as promising carrier materials. For instance, tetrahedral framework nucleic acids (tFNAs) have emerged as a novel type of nanoparticle, demonstrating strong anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic properties in multiple disease models.

Wang et al. [122] explored the therapeutic potential of tetrahedral framework nucleic acids (tFNAs) in treating SAP and its related multiorgan damage using a mouse model. Their findings showed that tFNA treatment effectively reduced SAP severity and organ injury by specifically lowering inflammatory cytokine levels in both tissues and blood, while also regulating the expression of key apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins (Figure 6B). Moreover, tFNAs helped preserve the normal structure of various organs including the pancreas, lungs, liver, and kidneys by limiting lymphocytic infiltration, a hallmark of inflammation. In the study, twenty-one mice were divided randomly into three groups: SAP treated with saline (Saline group), SAP treated with tFNAs (tFNA group), and a Sham Operation group (SO group). Following SAP induction, mice in the tFNA group received two intravenous injections of tFNAs (125 nM, 100 μL) via the tail vein at 30- and 60-minutes post-induction. The SO group underwent a sham surgical procedure, while the Saline group was administered an equal volume of saline instead of tFNAs. All animals were euthanized 24 hours after the procedure (Figure 6C). Using in vivo bioluminescence imaging, the researchers tracked the distribution of tFNAs within the body and found prominent accumulation in the pancreas, thymus, spleen, liver, and kidneys (Figure 6D).

In summary, this study demonstrates for the first time that tFNA therapy effectively alleviates SAP and its related multiorgan injury in mice. By modulating the release of inflammatory cytokines and regulating proteins involved in pathological cell death and apoptosis, tFNA treatment significantly curbed both local and systemic inflammation and prevented cell death, thereby halting disease progression and preserving normal tissue architecture in affected organs. Beyond protecting the pancreas from acute failure, tFNA therapy also mitigated damage to multiple organs, addressing a key complication associated with SAP.

(A) Schematic schematic depicting synthesis, targeting, and mechanism of bilirubin nanomedicine (BRSNPs). Reproduced with permission from ref. [121] Copyrights 2020, Elsevier. (B) Illustration of tFNAs treatment on severe acute pancreatitis. (C) Experimental scheme of tFNAs treatment alleviated Severe acute pancreatitis. (D) Images showing the biodistribution of tFNAs in the main organs of SAP mice using fluorescence. Adapted with permission from ref. [122] Copyrights 2025, American Chemical Society.

3.3.2 Extracellular vesicles

Currently, there is no particularly effective treatment for SAP, aside from supportive care, and the precise mechanisms behind AP remain incompletely understood. Recent research has highlighted the involvement of key proteins in pyroptosis, including pro-caspase-1, ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD), and NLRP3, which are activated during AP [123]. The inflammasome activation in damaged pancreatic acinar cells (PACs) leads to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, exacerbating pancreatic damage through pyroptosis, a type of programmed cell death that results in acute inflammation. Therefore, targeting inflammation and preventing PAC pyroptosis are essential for effective AP treatment [124].

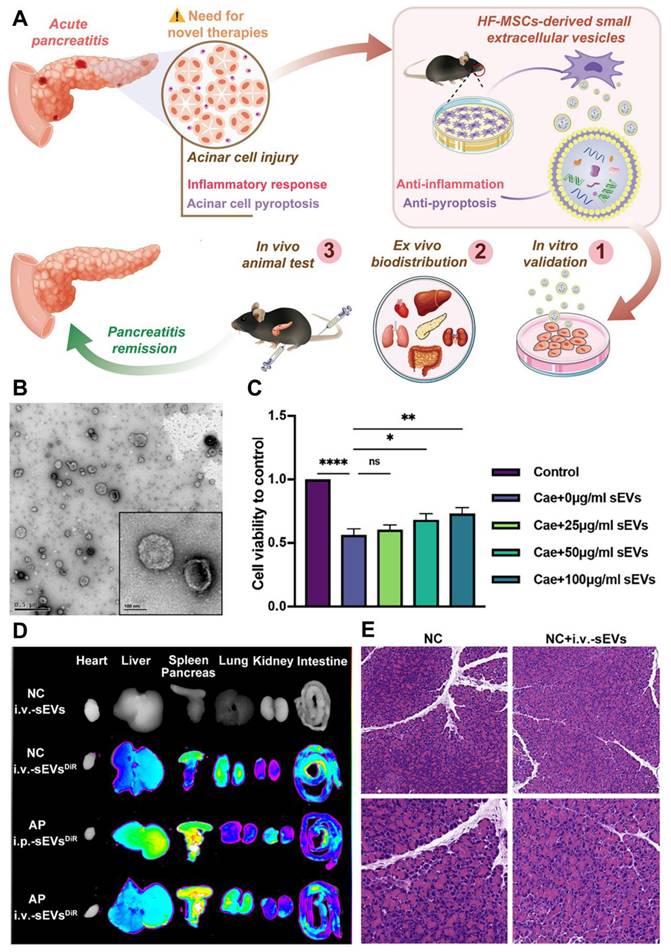

Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) show considerable promise in treating refractory pancreatic diseases by promoting angiogenesis, preventing PAC necroptosis, and supporting pancreatic tissue regeneration. Among various MSC types, hair follicle (HF)-derived MSCs are particularly attractive due to their ease of access, high proliferative capacity, and broad differentiation potential [125]. However, safety concerns such as iatrogenic tumor formation and immune rejection present challenges for MSC-based therapies. To address these concerns, researchers have suggested that MSCs might act via a paracrine mechanism, in which MSCs release therapeutic factors without needing to directly migrate to the injured tissue. One key component of this mechanism is the release of small extracellular vesicles (sEVs), which range from 30 to 150 nm in size and contain a variety of proteins, lipids, cytokines, and noncoding RNAs. MSC-derived sEVs have been shown to alleviate inflammatory conditions such as ulcerative colitis, acute liver injury, and renal injury [126].

In a study by Li et al. [127] the therapeutic potential of HF-MSC-derived sEVs for treating AP was investigated, focusing on their mode of action (Figure 7A). The study tested the effects of intraperitoneal (i.p.) and intravenous (i.v.) administration of sEVs in mice. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of purified sEVs revealed a distinct saucer-like structure with a lipid bilayer, confirming their typical morphology (Figure 7B). The results showed that higher concentrations of sEVs improved cell viability, with 100 μg/ml sEVs significantly enhancing cell survival compared to lower doses (Figure 7C). Biodistribution studies indicated that both i.p. and i.v. routes resulted in sEVs accumulating in the pancreas of AP-affected mice. Notably, i.p.-sEVs were also found in the liver and spleen, while i.v.-sEVs dispersed more widely across the lung, spleen, liver, and other organs (Figure 7D). These findings suggest that sEVs are capable of reaching the damaged pancreas, regardless of the administration route.

Histological analysis of pancreatic tissue revealed significant edema, inflammatory infiltration, and acinar cell necrosis in the AP group. In contrast, these pathological changes were less severe in the sEV-treated mice, suggesting a protective effect. The NC (normal control) group, whether or not treated with sEVs, showed no major changes in tissue pathology (Figure 7E). These results provide strong evidence that HF-MSC-derived sEVs could represent a promising therapeutic approach for reducing pancreatic damage in AP.

Overall, a new therapeutic effect of HF-MSC-sEVs, makes them a viable treatment option for AP. In both MPC-83 cells and AP animals, the treatment of sEVs reduced inflammation in acinar cells; the therapeutic effect may be due to the inhibition of pyroptosis signaling. Furthermore, in the caerulein-induced AP paradigm, intravenous sEV delivery was found to be more efficacious than intraperitoneal injection. In conclusion, the clinical use of extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics in incurable pancreatic illnesses may be encouraged by this cell-free method based on sEVs produced from HF-MSCs, which has significant promise as a safe and effective therapy option for AP.

3.3.3. Multitargeting strategies for pancreatitis therapy

In AP, the inflammatory microenvironment is characterized by the presence of ROS, inflammatory cells, hydrogen ions (H+), and excess digestive enzymes, all of which contribute to the worsening of the disease through various mechanisms [128]. Due to this complexity, relying on a single biomarker for diagnosis and treatment is often insufficient. The involvement of multiple inflammation-related factors opens up new possibilities for improving both the diagnosis and treatment of AP [129]. Recently, there has been progress in developing multitargeted drug delivery systems. Among these, dual-targeted delivery approaches have shown greater potential by effectively exploiting the inflammatory microenvironment to enhance drug distribution and therapeutic outcomes [130,131].

Dai et al. [132] created a nanosystem to enable synergistic oxidation-chemotherapy with self-enhanced drug release. This system is not only sensitive to pH changes, which improves drug uptake by altering its surface charge, but it also responds to reactive oxygen species (ROS) by releasing cephaeline and β-lapachone. This dual responsiveness helps to overcome multidrug resistance within tumors and promotes the destruction of cancer cells. In another study, Gou et al. [133] developed surface-functionalized (SF) nanoparticles (CS-CUR-NP) by coating with chondroitin sulfate (CS). These nanoparticles are designed to release curcumin (CUR) in response to pH changes and ROS. Moreover, CS-CUR-NP can specifically deliver drugs to inflammatory sites and target macrophages, making them effective for treating ulcerative colitis. Interestingly, similar nanoparticle systems have also been engineered for the diagnosis and treatment of AP.

(A) Demonstration of HF-MSC-sEVs attenuated AP and the potential mechanism. (B) Examining HF-MSC-sEV morphology under TEM. (C) Effects of different HF-MSC-sEV concentrations on MPC-83 cell viability. (D) NIRF measurement of the fluorescence intensities of the main organs in mice and ex vivo organ imaging. (E) Typical pathological alterations in pancreatic tissues stained with H&E sections at ×200 and ×400 magnification. Adapted with permission from ref. [127] Copyrights 2022, Elsevier.

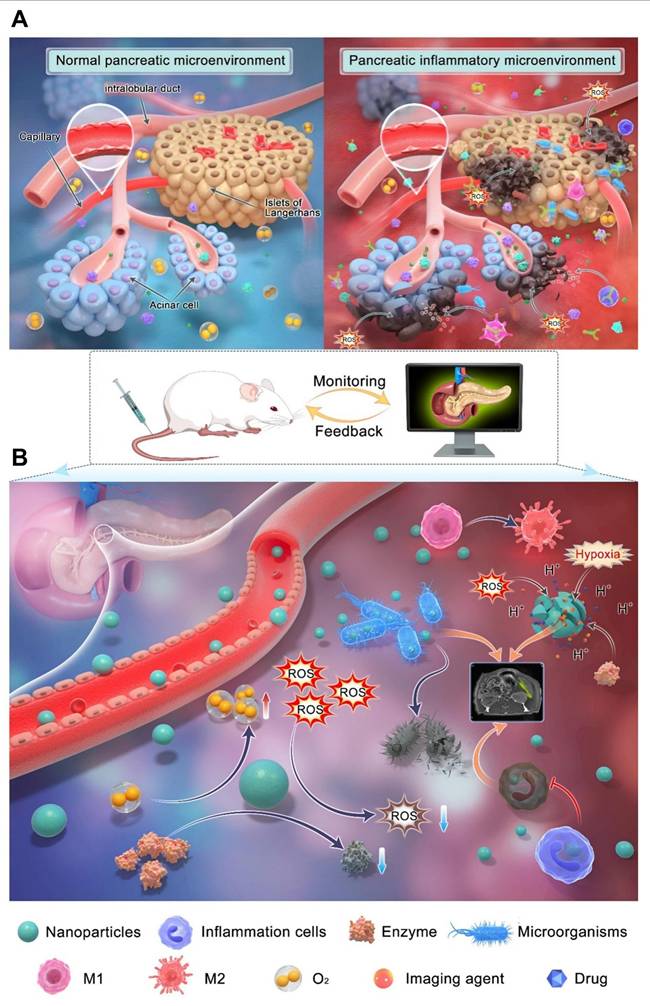

Liu et al. [30] developed nano-theranostic agent, TMSN@PM, that induces excessive ROS generation and mild acidity. This multifunctional platform offers both therapeutic treatment and MRI imaging capabilities for AP. The development of TMSN@PM represents a significant step toward combining diagnosis and therapy in AP management, and it is expected that future research will further advance multifunctional nanoplatform applications for this condition. AP has a complex pathogenesis involving factors such as trypsinogen activation, calcium overload, and mitochondrial dysfunction, alongside diverse causes and clinical symptoms, making its conventional diagnosis and treatment challenging. Early in AP, trypsin activation within pancreatic acinar cells triggers the activation of other digestive enzymes, leading to pancreatic tissue injury. The activation of immune cells like macrophages releases proinflammatory cytokines, which intensify pancreatic inflammation. Excessive ROS production further exacerbates cell damage by generating various harmful molecules. This process activates multiple signaling pathways, including nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) and toll-like receptors (TLR), driving an inflammatory cascade. Additionally, pancreatic cell dysfunction and enhanced glycolysis contribute to a reduction in pH levels. As illustrated in (Figure 8A), the AP pathological process involves an accumulation and overexpression of substances such as H+, digestive enzymes, ROS, and inflammatory cells, creating an inflammatory microenvironment crucial to disease progression.

Figure 8B highlights how the complex microenvironmental changes in AP complicate diagnosis and treatment but also offer new therapeutic targets. Targeting multiple pathways simultaneously is likely to be more effective than focusing on a single factor. Therefore, designing multitarget nanocarriers and discovering additional targets could improve diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for AP. Advances in nanotechnology have addressed many limitations of traditional diagnosis and treatment methods. Nanomaterials with high specificity can enhance detection sensitivity and reduce response times, improving diagnostic accuracy. Various biosensors and nanoprobes have been engineered to detect inflammatory microenvironment markers. Through surface modification, nanomaterials can optimize their properties, enabling targeted accumulation in specific organs and amplifying detection signals. This has significantly improved pancreatic enzyme detection and pancreatic tissue imaging, increasing AP diagnosis rates.

On the therapeutic front, a range of nanodrugs and nanocarrier systems have been developed to repair AP-induced damage. These innovations overcome issues related to poor solubility and bioavailability of conventional drugs and enhance drug delivery efficiency. Moreover, therapeutic nanomaterials exhibiting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antiapoptotic effects have been designed to target key elements within the inflammatory microenvironment. By leveraging surface functionalization and stimulus-responsive materials, drug carriers can be engineered to target abnormal biochemical markers such as elevated H+, ROS, and digestive enzymes within the inflammatory microenvironment of AP. This targeted delivery prolongs drug retention at inflammation sites in the pancreas and related organs, offering a promising strategy to improve treatment outcomes for AP.

Despite significant progress, nanotechnology still faces many challenges and limitations in diagnosing and treating AP by targeting the inflammatory microenvironment. One major hurdle is the unique anatomical structure of the pancreas, which includes a specialized blood-pancreas barrier (BPB) composed of the basement membrane, capillary endothelial cells surrounding glandular follicles, and other components. While this barrier protects the pancreas from pathogens, it also restricts drug penetration, resulting in few drugs being able to effectively cross it and achieve therapeutic concentrations within the organ. Currently, only a limited number of nanocarriers are designed to target the inflammatory microenvironment, leading to low delivery efficiency. Future developments should focus on designing carriers that combine the advantages of multiple delivery systems to improve both targeting efficiency and biosafety. Another limitation is the lack of well-defined, precise targets for AP due to its still unclear pathophysiology. This has limited the development of nanodrugs specifically aimed at the pancreatic inflammatory environment. Most current nanodrugs rely on passive targeting mechanisms, such as the ELVIS effect, which increases drug accumulation in inflamed tissues but also causes off-target effects and low delivery precision. Therefore, there is a need to develop actively targeted nanodrugs that recognize specific molecular markers of inflammation to enhance delivery efficiency and therapeutic outcomes [134].

Recent advances in genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have made it possible to identify more accurate biomarkers for pancreatitis, improving early diagnosis and treatment efficacy. While designing functional nanomaterials to target these diverse markers in the inflammatory microenvironment is a promising direction, several issues hinder their widespread clinical application.

(A) Schematic diagram of microenvironmental targets of pancreatic inflammation. (B) Schematic diagram of different modes of interaction between nanoparticles and targets in the inflammatory microenvironment. Adapted with permission from ref. [30] Copyrights 2024, Springer Nature.

Among these, biosafety remains a critical concern. The lack of standardized protocols and regulatory guidelines for evaluating the toxicity of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems complicates the assessment of their potential risks. Furthermore, because the human immune system's response to drugs is complex, animal models often fail to accurately replicate the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and organ-specific effects of nanomaterials in humans. Consequently, most current studies rely heavily on animal experiments, which may not fully predict human responses. Additionally, various animal models exist for AP, each reflecting different causes and features of the disease [135,136]. Researchers must carefully select the most appropriate model based on its pathophysiological relevance and limitations for their specific study aims. However, the complex and multifactorial nature of human AP makes it difficult for animal models to perfectly mimic the condition, and the technology for establishing these models is still developing. To facilitate the clinical translation of nanomedicines for AP, it is essential to establish standardized scientific evaluation systems, improve animal models, develop robust evaluation criteria and testing methods, and advance research in nanotoxicology. Addressing these challenges will be crucial for safely and effectively harnessing nanotechnology in the diagnosis and treatment of AP.

4. Therapeutic antiinflammation strategies for pancreatitis treatment

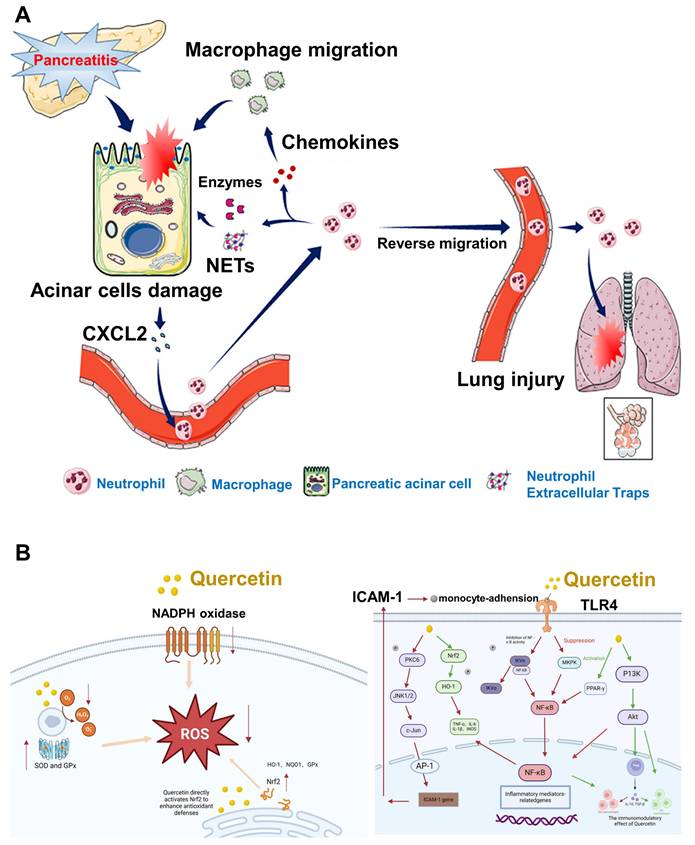

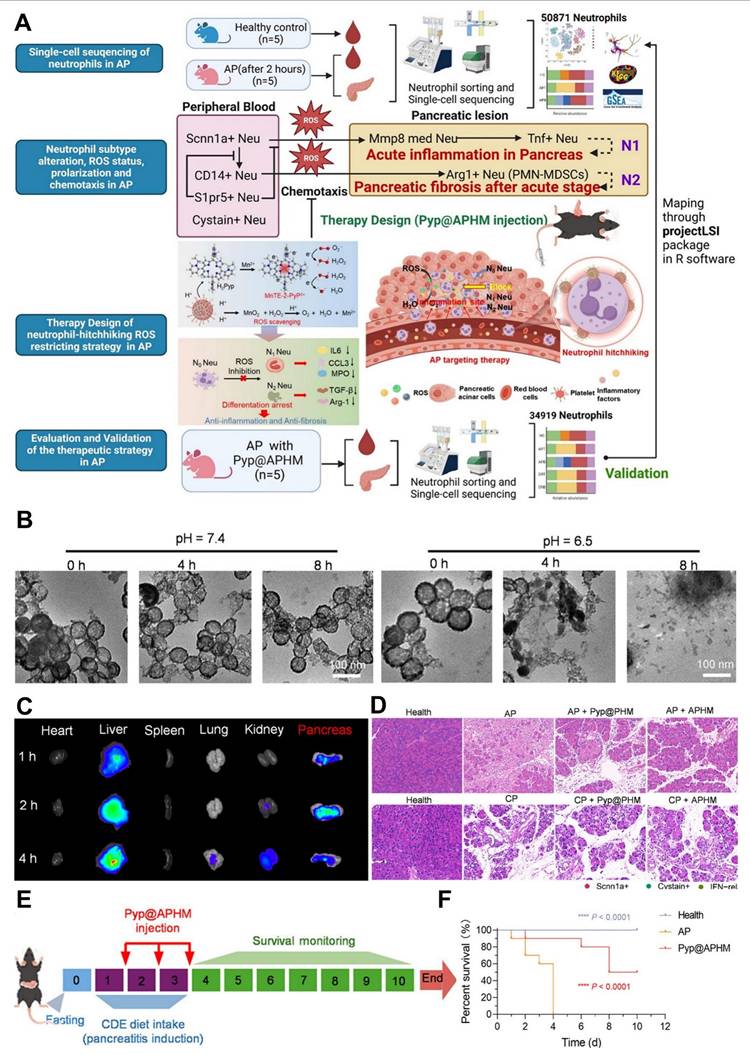

Oxidative stress plays a pivotal role in the development of AP, stemming from a disruption in the balance between ROS and the body's antioxidant defense mechanisms [137]. This imbalance causes direct cellular damage and contributes to the progression of local pancreatic inflammation into systemic complications, such as multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) [138]. Despite the availability of supportive treatments like fluid replacement, nutritional intervention, and pain control, no pharmacological solution has been identified that can fully prevent or reverse the disease process. Neutrophils are central to the inflammatory cascade in AP [139]. Experimental studies have indicated that reducing neutrophil numbers can lead to a notable decrease in tissue injury. However, this approach often leads to compromised immune function [140]. In AP, excessive or misdirected neutrophil activity not only worsens pancreatic injury but also causes damage to remote organs, especially the lungs. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), when administered rectally prior to ERCP procedures, have been shown to reduce post-ERCP pancreatitis by limiting neutrophil migration into pancreatic tissue [141]. Wan et al. [142] demonstrated that AP exacerbation involves the mobilization of granulocytes, accumulation of neutrophils, and the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), as illustrated in (Figure 9A). This discovery introduces opportunities for more focused therapies that can attenuate the inflammatory response, minimize damage caused by neutrophils, and reduce overall immune system compromise.

Quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid found in various fruits and vegetables, has gained attention due to its potent antioxidant capabilities. It helps protect cells by neutralizing ROS, reducing lipid peroxidation, and stimulating the synthesis of intracellular glutathione (GSH), a key antioxidant molecule. Studies in chronic kidney disease models have shown that quercetin can reverse endothelial dysfunction by lowering oxidative damage. Further in vitro evidence from Hossein et al. [143] revealed that quercetin treatment significantly reduced ROS levels, elevated sulfhydryl group concentrations, and enhanced cell viability in endothelial cells subjected to oxidative stress. In pancreatitis models, quercetin has consistently demonstrated its ability to diminish oxidative damage in the pancreas by both scavenging harmful radicals and activating antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px). In cerulein-induced AP models, Faiza et al. [144] observed that quercetin treatment markedly suppressed ROS production while increasing the levels of these protective enzymes. These findings suggest that quercetin not only protects pancreatic tissues from oxidative stress but also enhances the body's internal antioxidant defense systems. The Nrf2 pathway, a crucial regulator of oxidative stress responses, is also positively influenced by quercetin. Jiang et al. [145] demonstrated that quercetin activates Nrf2 signaling, which boosts the production of GSH and enhances cellular resilience to oxidative injury mechanisms depicted in (Figure 9B).

In addition to its antioxidant functions, quercetin also demonstrates significant anti-inflammatory activity. It modulates key pro-inflammatory pathways, notably NF-κB and MAPK, which are both heavily involved in the progression of pancreatic inflammation. Quercetin's capacity to inhibit these signaling cascades helps to reduce cytokine release and tissue injury. The mechanism suggests that quercetin has the potential to serve as a broad-acting therapeutic agent in AP by simultaneously addressing oxidative stress and inflammation.

Nevertheless, a major barrier to the clinical use of quercetin is its limited bioavailability. Poor absorption and rapid metabolism restrict its therapeutic effectiveness, particularly in acute and severe conditions like AP. Advanced drug delivery systems such as nanoparticles and liposomal encapsulation have been proposed to enhance its systemic availability, but further research is needed to ensure their safety and efficacy in clinical settings. There is also insufficient data regarding optimal dosing regimens, potential side effects, and interactions with standard medications such as corticosteroids or N-acetylcysteine (NAC). This raise concerns that combining quercetin with other therapies might lead to unpredictable outcomes. Even so, quercetin's broad pharmacological profile targeting oxidative damage, immune dysfunction, and inflammation positions it as a promising candidate for future AP therapies. Compared to single-target agents, quercetin offers the advantage of a multi-target approach. Although current evidence from laboratory models is encouraging, clinical trials are necessary to determine its practical utility. With additional research, quercetin could transition from an experimental compound to a mainstream therapeutic option for pancreatitis and related inflammatory diseases.

(A) The process by which neutrophils worsen AP. Reproduced with permission from ref. [142] Copyrights 2021, Frontiers (B) Mechanism of quercetin-induced Nrf2 activation and increased antioxidant defenses, and the Quercetin-mediated signaling pathway in the control of AP. Adapted with permission from ref. [145] Copyrights 2025, Frontiers.

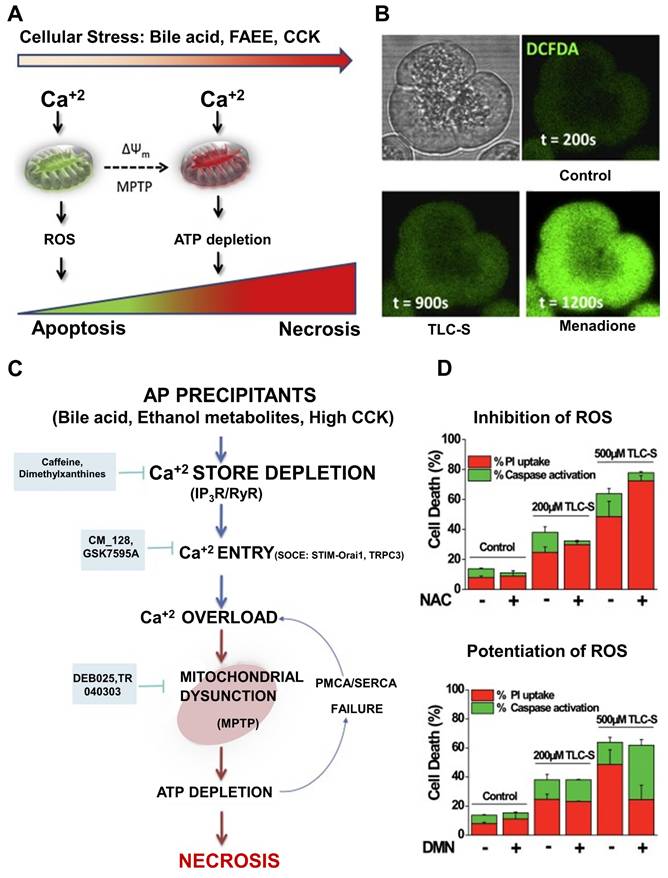

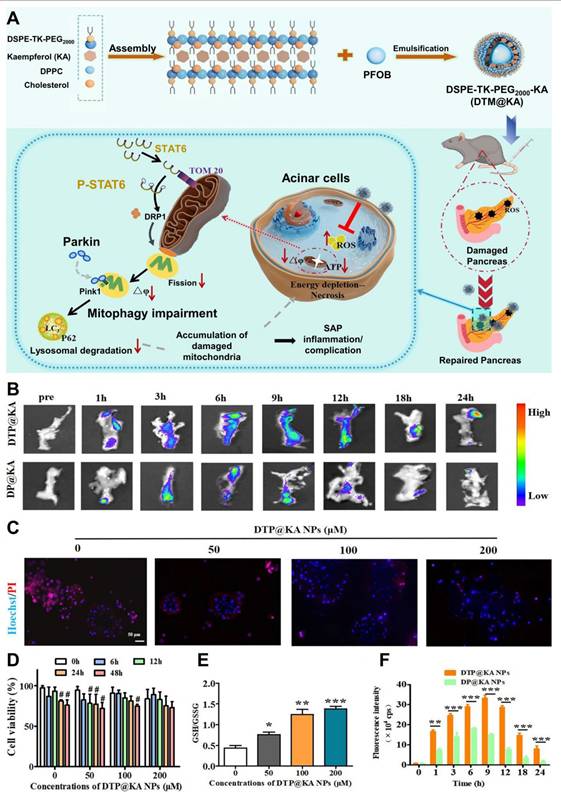

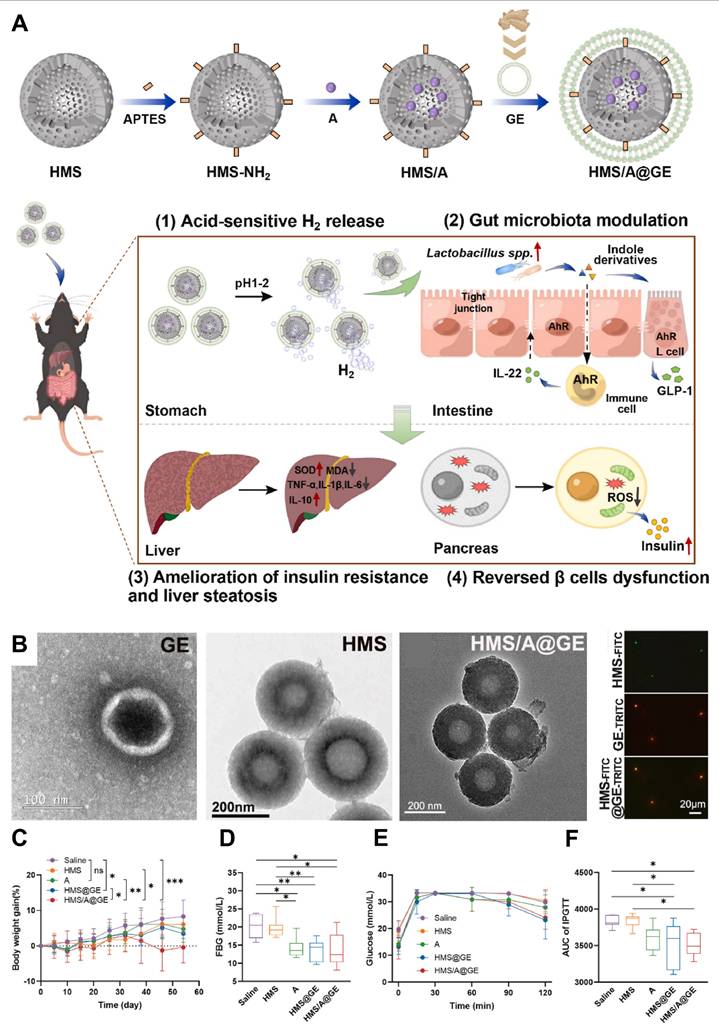

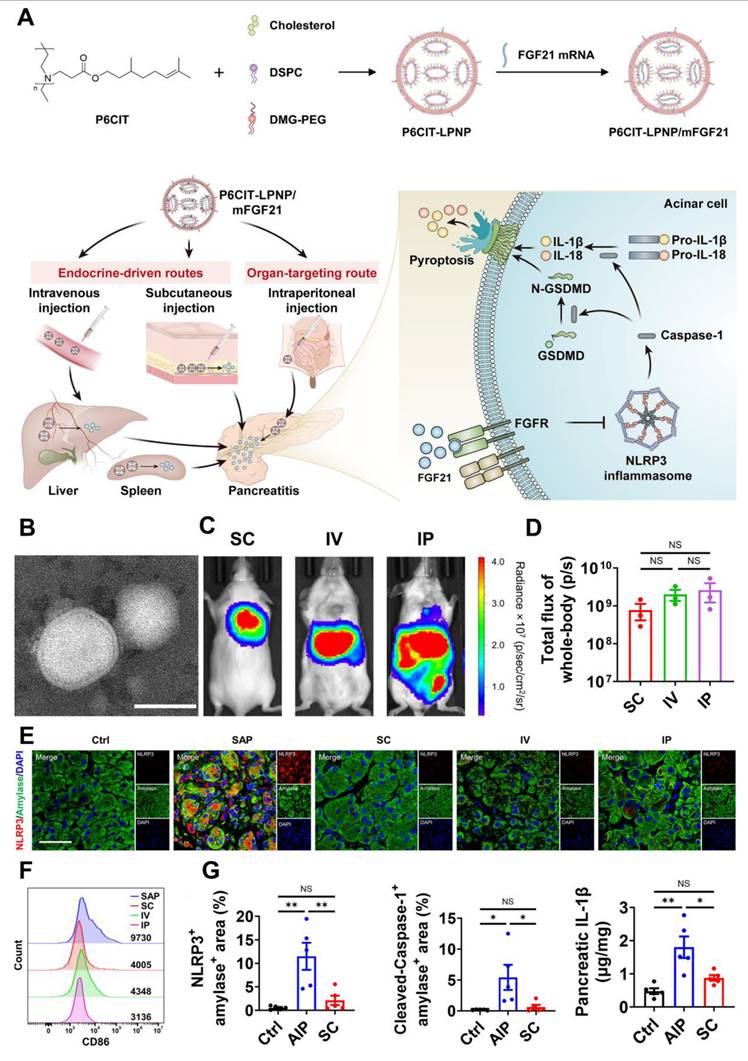

AP involves extensive pancreatic injury characterized by vacuolization, necrotic cell death, and early activation of digestive enzymes. To avoid such cellular damage, it is crucial to maintain a tightly regulated balance among Ca+2 release from intracellular reservoirs, Ca+2 influx, and extrusion processes [146]. Various triggers of AP disrupt this equilibrium, leading to intracellular Ca+2 overload in acinar cells, which contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction through the formation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), subsequent ATP depletion, and cell necrosis. Oxidative stress has been implicated in the progression of AP and may influence Ca+2 dynamics within the acinar cells [147]. However, its precise mechanistic role remains unclear, and clinical trials using antioxidant therapies have largely been unsuccessful. It is hypothesized that the pattern of cell death in AP may be partially dictated by ROS production [148].