13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2022; 12(14):6130-6142. doi:10.7150/thno.74194 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Lgr5+ cell fate regulation by coordination of metabolic nuclear receptors during liver repair

1. College of Veterinary Medicine/College of Biomedicine and Health, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, Hu Bei, 430070, China.

2. Department of Diabetes Complications and Metabolism, Diabetes and Metabolism Research Institute, Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

3. Department of Nephrology, First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, Nephrology Institute of the Chinese People's Liberation Army, State Key Laboratory of Kidney Diseases, National Clinical Research Center for Kidney Diseases, Beijing Key Laboratory of Kidney Disease Research, Beijing 100853, China.

Received 2022-4-20; Accepted 2022-8-6; Published 2022-8-15

Abstract

Background: Leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) is a target gene of Wnt/β-Catenin which plays a vital role in hepatic development and regeneration. However, the regulation of Lgr5 gene and the fate of Lgr5+ cells in hepatic physiology and pathology are little known. This study aims to clarify the effect of metabolic nuclear receptors on Lgr5+ cell fate in liver.

Methods: We performed cell experiments with primary hepatocytes, Hep 1-6, Hep G2, and Huh 7 cells, and animal studies with wild-type (WT), farnesoid X receptor (FXR) knockout mice, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) knockout mice and Lgr5-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG mice. GW4064 and CDCA were used to activate FXR. And GW7647 or Wy14643 was used for PPARα activation. Regulation of Lgr5 by FXR and PPARα was determined by QRT-PCR, western blot (WB) and RNAscope® in situ hybridization (ISH) and immunofluorescence (IF), luciferase reporter assay, electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). Diethyl 1,4-dihydro-2,4,6-trimethyl-3,5-pyridinedicarboxylate (DDC) diet was used to induce liver injury.

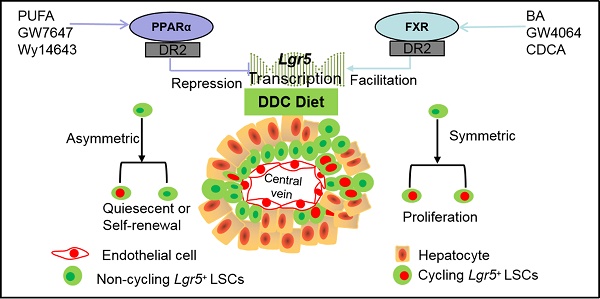

Results: Pharmacologic activation of FXR induced Lgr5 expression, whereas activation of PPARα suppressed Lgr5 expression. Furthermore, FXR and PPARα competed for binding to shared site on Lgr5 promoter with opposite transcriptional outputs. DDC diet triggered the transition of Lgr5+ cells from resting state to proliferation. FXR activation enhanced Lgr5+ cell expansion mainly by symmetric cell division, but PPARα activation prevented Lgr5+ cell proliferation along with asymmetric cell division.

Conclusion: Our findings unravel the opposite regulatory effects of FXR and PPARα on Lgr5+ cell fate in liver under physiological and pathological conditions, which will greatly assist novel therapeutic development targeting nuclear receptors.

Keywords: FXR, PPARα, Lgr5, Proliferation, Symmetric or asymmetric cell division

Introduction

The liver possesses excellent regenerative ability and exerts multiple physiological functions. Insufficient liver regeneration leads to liver failure [1]. In addition, chronic liver disease may evoke over-proliferation of cells to induce liver neoplasia [2, 3]. Therefore, exploring the cell source for newly generated hepatocytes after injury and the regulatory mechanism underlying the initiation and termination of hepatocyte proliferation should be the research focus.

Lgr5 is a target gene of Wnt/β-catenin and is widely known as an important tissue stem cell marker [4]. Studies showed that small Lgr5-LacZ cells appear around near the bile ducts when the liver is injured [5]. And Lgr5+ cells isolated from injured liver could be clonally expanded into organoids in vitro and differentiated to functional hepatocytes in vivo [5]. Likewise, another study showed that carbon tetrachloride treatment promotes Lgr5+ liver stem cell proliferation and improves liver fibrosis, whereas Lgr5 knockdown worsens fibrosis [6]. Besides, human liver bile duct-derived Lgr5+ bi-potent progenitor cells after prolonged culture are highly stable at the chromosome structural level [7]. These results suggested that Lgr5+ cells are beneficial to liver regeneration.

However, other studies suggest that Lgr5+ cells induce the occurrence and development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [8, 9]. Lgr5+ cells are functionally similar to the cancer initiating cells, and they are capable of forming tumors and resisting chemotherapeutic drugs [9]. A clinical study has reported that 77 out of 188 HCC specimens showed positive staining for Lgr5, and the occurrence frequency of Lgr5 in tumor area was remarkably higher than that in the non-tumor area. Furthermore, Lgr5 expression and HCC progression showed a positive correlation [10]. Importantly, Lgr5 deletion notably impedes initiation of organoid and tumor [10]. Since Lgr5+ cells may be a double-edged sword for liver injury and repair, it is particularly important to reveal the spatial and temporal regulatory mechanism of Lgr5.

FXR regulates Lgr5+ intestinal stem cell proliferation [11]. FXR, as a transcription factor, is activated by a specific ligand such as bile acids (BA) [12]. Both hepatic FXR and intestinal FXR promote liver regeneration/repair, alleviate liver regeneration defect, and prevent cell death [13]. Recently, glutamine metabolism has been found to promote activation of Wnt signaling, increase expression of Lgr5, and enhance functions of stem cell [14]. Furthermore, FXR controls amino acid catabolism and ammonium detoxification through ureagenesis and glutamine synthesis in liver [15]. It has been reported that PPAR activation in intestinal crypts suppresses Wnt signal and promotes the loss of stemness of the Lgr5+ stem cells [16]. Besides, PPARα, belonging to the PPARs, regulates multiple biological processes [17]. PPARα is a major inducer of hepatic oxidative phosphorylation [18] which is important for stem cell fate in various tissues [19]. And both of FXR and PPARα can bind to the same binding sites using RXR as cofactor. However, whether FXR or PPARα regulates Lgr5 in the liver has not been reported yet. Understanding the regulatory mechanisms by which liver stem cells utilize metabolic nuclear receptors will disclose how liver maintain homeostasis and injury repair.

In this study, we further explored the response of Lgr5 cells to liver damage, and the regulation of Lgr5 cell fate by metabolic nuclear receptors.

Methods

All animal studies and procedures followed the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals of Huazhong Agricultural University. FXR knockout (KO) mice (# 007214) and PPARα knockout mice (# 008154) were brought from Jackson Laboratory (JAX, USA). Lgr5-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG mice (EGE-WXH-042) were bought from Biocytogen (Beijing, China). Mice were administrated with either vehicle (80% PEG-400 and 20% Tween 80), or GW4064 (MCE, HY50108, 50 mg/kg body weight), or GW7647 (Cayman, 265129-71-3, 5 mg/kg body weight) or Wy14643 (Cayman, 50892-23-4,100 mg/kg body weight) twice a day for 2 consecutive days, if no otherwise specified [20]. Mice were administrated with either vehicle or CDCA (Sigma, 700198P, 20 mg/kg body weight) once per day for 7 consecutive days [21]. For DDC injury experiments, 6-8 week (wk) old mice were fed with 0.1% DDC diet for 7 days [22]. For lineage tracing, heterozygous Lgr5-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648, 100 mg/kg body weight/day) once per day for 3 days and stop injection for 7 days before treatment. BrdU (Sigma, B5002, 50 mg/kg) was injected twice per day for 2 days before sacrifice. Mice were anesthetized to obtain blood and livers. For EdU (Servicebio, G5059) labeling, mice were injected with EdU (5 mg/kg) for 4 h or 24 h and then sacrificed to collect liver samples and processed for EdU detection according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Servicebio, G1601).

Cell culture

Primary hepatocytes were isolated by collagenase perfusion of the liver according to Taniai with minor modification [23]. Primary hepatocytes, Hep G2, Hep 1-6, and Huh 7 cells were incubated in H-DMEM (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) and 100 IU/mL penicillin-streptomycin (Hyclone, sv30010). All the cells were cultured in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were treated with GW4064 (10 μM), GW7647 (10 μM), Wy14643 (100 μM) or MK886 (TOPSCIENCE, T6893, 5 μM) for 24 h prior to RNA isolation [20, 22, 24, 25]. In order to detect the specificity of agonists, primary hepatocytes were isolated from WT, FXR KO or PPARα KO mice and then co-treated with different dose of GW4064 (1.0 μM or 10 μM) and GW7647 (0.1 μM or 1.0 μM) for 24 h [20, 26-28].

QRT-PCR

By using RNAiso plus (Takara, Japan), total RNA was isolated and purified, and the first strand cDNA synthesis kit (TOYOBO, Japan) was used to transcribe the obtained RNA into cDNA. The cDNA was diluted and used for the QRT-PCR. In a 10 μL reaction system, the samples were run with the SYBR Green QRT-PCR mix (TOYOBO, Japan). Data were analyzed in the ABI CFX Connect TM Real-Time PCR Detection System (ABI, USA). The mRNA level of the interest gene was normalized to housekeeping gene 36B4 or Gapdh. The primers were listed in Table S1.

Western blot

Mouse livers and primary hepatocytes were extracted with protein lysis buffer (Beyotime, China, P0013) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail. BCA Kit (Beyotime, China, P0009) was used to assess the protein concentration. Proteins (40 µg) were separated on a 10% or 4-20% polyacrylamide precast SDS gel followed by blotting on PVDF membranes (Millipore Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were probed with the following antibodies against: anti-LGR5 (Thermofisher, MA5-25644), anti-SHP (Abclone, A16454), anti-CPT1a (Santa Cruz, sc-393070) and anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz, sc-293335) at 4 °C overnight. The secondary antibody was incubated at the dilution concentration of 1:5,000 for 1.5 h at room temperature. Then the membrane was exposed with ECL reagent (Juneng, K-12045-D10) in the imaging system (SYNGENE, G: Box). The density of the bands was analyzed by using Image-J software.

Molecular cloning and cell-based luciferase reporter assay

Putative FXREs and PPREs in Lgr5 promoter sequence were analyzed using an online algorithm (NUBIScan). According to this prediction, the gene promoter fragments (position -3332 to -1824, -1994 to -771, -942 to +161 relative to the transcription start site) were amplified by PCR using mouse genomic DNA. Afterwards, these fragments were individually inserted into the pGL3-basic plasmid. To estimate the firefly luciferase activity, the above plasmids together with the phRL-TK plasmid were individually co-transfected into Hep 1-6 cells or Hep G2 cells, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) following the manual. After incubation for 6 h, the cells were cultured with fresh medium supplied with vehicle, CDCA or GW4064, or GW7647 and collected 24 h later. Dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, USA) was used to detect the luciferase activity by using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL (Thermo Scientific, USA). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized with renilla luciferase activity as internal control.

EMSA

Nuclear extracts were prepared from GW4064 or GW7647-treated livers using the Active Motif Nuclear Extract Kit (Active Motif, CA, USA) and BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime, Jiangsu, China) was used to detect the protein concentrations of nuclear extracts. Labeled and unlabeled probes (Sangon, Shanghai, China) containing the binding site were synthesized (Table S1). The DNA binding activity of FXR or PPARα was determined by a chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Beyotime, GS009) according to instruction with minor modification to liver samples pretreatment.

ChIP

GW4064-treated and GW7647-treated cells or livers were subjected to ChIP assays according to the protocol (Beyotime, P2078). Then the samples were immunoprecipitated with anti-FXR (Santa Cruz, sc-25039X), anti-PPARα antibody (Santa Cruz, sc-398394), anti-NCOR (Abcam, ab3482), anti-NCOR2 (Abcam, ab24551) and mouse IgG antibody (Beyotime, A7028) or recombinant rabbit IgG antibody (Abcam, ab172730) acting as a negative control. The captured chromatin was first eluted, and then uncross-linked, finally the DNA was recycled. Using the primer pairs (Table S1) spanning the specific promoter region, the captured DNA by ChIP was subjected to PCR amplification.

Plasma transaminase levels and histological analysis

The ALT and AST levels in the plasma were measured with assay kits purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng (C009-2, C010-2). The livers were soaked in 4% formaldehyde for 1 day, and subsequently embedded in paraffin for histologic assessment. The prepared slices were further deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin-eosin staining or Sirius red staining.

Immunofluorescence staining

For histological analysis, the collected mouse livers were snap-frozen in OCT for preparation of frozen sections. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections must be deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval for satisfactory immunostaining. For immunofluorescence staining, the liver sections (6 μm) were blocked in PBS containing 10% goat serum and 1% Triton X-100, then the slices were incubated with primary antibodies, namely, anti-CK19 (Servicebio, GB12197), anti-GS (Santa Cruz, sc-74430), anti-GFP (Proteintech, 50430-AP or Santa Cruz, sc-9996), anti-BrdU (Servicebio, GB12051), anti-HNF4α (Ab41898) and anti-β-actin (Proteintech, 20536-1-AP). After being incubated with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, A-11034, A-21424), slices were counter-stained with DAPI (Invitrogen, Ab104139). Finally, the results were observed under confocal microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH or Nicol Laser Confocal Microscope).

RNAscope® In situ hybridization

Fluorescence ISH of Lgr5, Gs, Pck1 and Hnf4α was carried out using the RNAscope® ISH Assay (ACD, 323100), following the manufacturer's instructions. Concisely, prepared cryosections were fixed in formaldehyde for 15 min at 4 °C, dehydrated, and pre-treated in hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by 0.5 h digestion in protease III. Prepared formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver sections were baked, deparaffinized and then pre-treated in hydrogen peroxide, followed by target retrieval and protease digestion. Subsequently, slices were pre-amplified and amplified in terms of the directions. The resultant sections were counterstained using mounting medium with DAPI. The results were observed under laser confocal microscope (LSM710, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH or Nicol Laser Confocal Microscope) with fixed parameters. Signal intensity was adjusted in each channel in term of their histograms. The obtained parameters after adjustment were used for the whole batch of pictures. The probe information was listed in Table S2.

Software-Intensity measurement

Image Pro Plus (Image J), as an analysis program, was used to analyze and quantify data from photomicrographs. In this study, the analyses were performed as follows: Integrated optical density was used to quantify the intensity of probes binding to the structures [29]. At least three mice per group and at least three confocal images were used for each mouse were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

All data from experiments were presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical significance differences between groups were determined by Student's t-test or ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05 (*), P<0.01 (**), P<0.001 (***). In all cases, data from at least 3 independent samples and 3 independent experiments were used.

Results

FXR activation induces Lgr5 expression

The location of Lgr5+ cells in the adult liver was recently reported [30-32]. In this study, we reproduced these results by PCR, WB, IF, RNAscope® ISH and lineage tracing. As shown in Figure S1A-H, Lgr5 was expressed in normal liver and Lgr5+ hepatocytes were mainly located around the perivenous (PV) area.

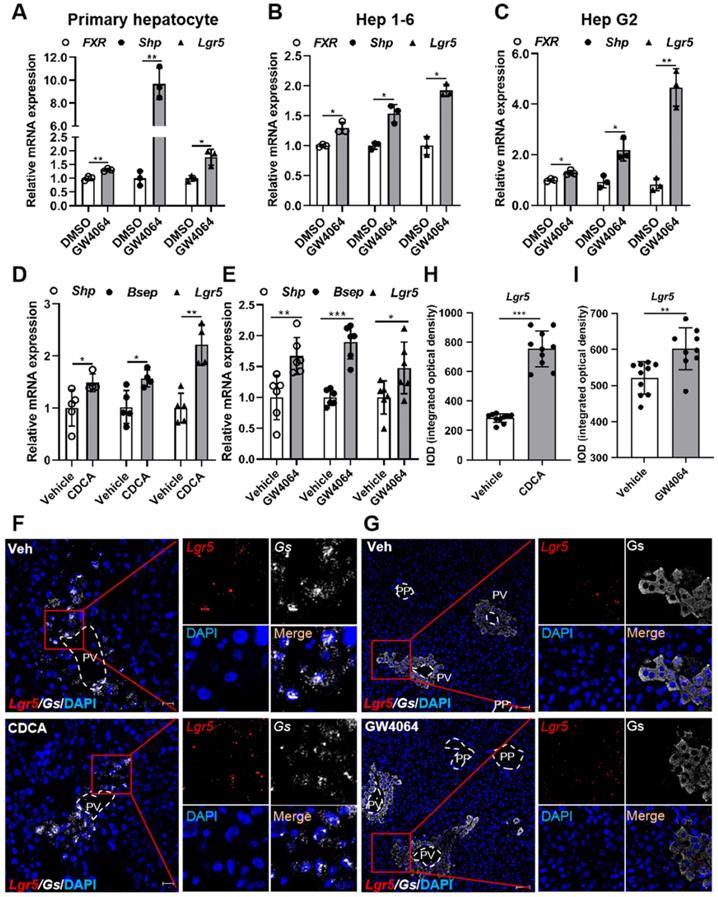

To determine whether FXR regulates Lgr5 expression in liver, we treated primary hepatocytes, Hep 1-6 cells, and Hep G2 cells with FXR agonist GW4064. Results showed that GW4064 induced FXR expression, and small heterodimer partner (Shp) was up-regulated, resulting in FXR activation, thus increasing Lgr5 expression (Figure 1A-C). These results indicate that FXR regulates Lgr5 expression in vitro. Additionally, QRT-PCR and WB results indicated that the regulation was dose dependent in WT hepatocytes and was abolished by FXR-/- mouse cells (Figure S2A-D).

To further confirm the results in vivo, FXR agonist CDCA or GW4064 was administrated intragastrically to WT mice. Up-regulation of Shp and bile salt export pump (Bsep) indicated the activation of FXR, which in turn strongly promoted Lgr5 expression (Figure 1D-E). RNAscope® ISH confirmed CDCA and GW4064 treatment resulted in increased Lgr5 expression (Figure 1F-I). Thus, we conclude that FXR activation induces Lgr5 expression in vitro and in vivo.

PPARα activation suppresses Lgr5 expression

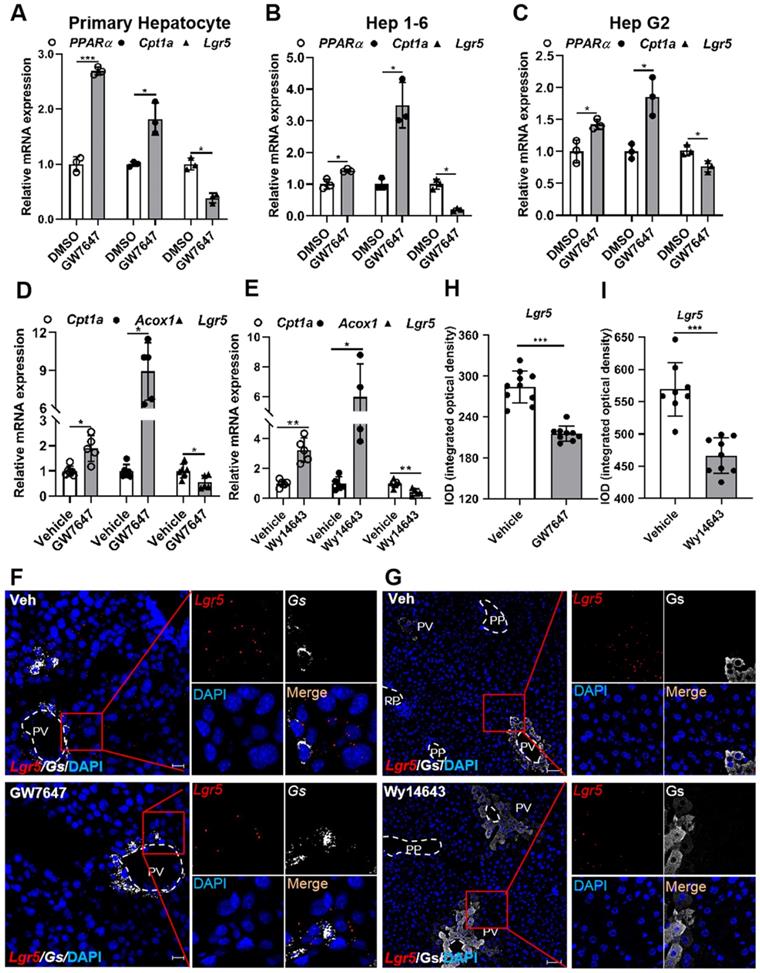

To examine whether PPARα regulates Lgr5 expression in liver, primary hepatocytes, Hep 1-6 cells, or Hep G2 cells were treated with PPARα agonist GW7647. The results showed that GW7647 induced PPARα expression, and Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a (Cpt1a) was significantly up-regulated, thus activating PPARα, eventually decreasing Lgr5 expression (Figure 2A-C). Additionally, QRT-PCR and WB results illustrated that different doses of GW7647 induces down-regulation of Lgr5 expression in hepatocytes from WT mice and was abolished in PPARα KO mouse cells (Figure S2E-H). Similarly, PPARα activation by GW7647 reduced Lgr5 expression in Huh 7 cells, and this reduction effect was abolished by PPARα inhibitor MK886 (Figure S3A). Besides, Wy14643, another ligand of PPARα, decreased the expression of Lgr5 in primary hepatocytes (Figure S3B). These results indicate that PPARα activation suppresses Lgr5 expression in vitro.

To further verify the results in vivo, mice were treated with the PPARα agonist GW7647 or Wy14643. The significantly increased expression of Cpt1a and Acyl-CoA oxidase 1 (Acox1) demonstrated the activation of PPARα (Figure 2D-E). GW7647 and Wy14643 drastically decreased Lgr5 expression, and these results were further confirmed by RNAscope® assays (Figure 2F-I). To determine whether PPARα specifically regulated Lgr5 transcription, we treated WT and PPARα-/- mice with GW7647 or vehicle. QRT-PCR results revealed that PPARα agonist notably suppressed the expression of Lgr5 in WT, but this suppression effect was abolished in PPARα-/- mice (Figure S3C-D). RNAscope® ISH further confirmed these results (Figure S3E). Quantification of the signals was presented in Figure S3F. Based on above results, we conclude that PPARα activation reduces Lgr5 expression in vitro and in vivo.

Pharmacological activation of FXR induces Lgr5 expression. (A-C) QRT-PCR analysis of FXR, Shp and Lgr5 expression in primary hepatocytes, Hep 1-6 cells and Hep G2 cells treated with GW4064 (10 µM) or DMSO for 24 h. (D) Mice were orally treated with either vehicle or CDCA (20 mg/kg) once a day for 7 days. Then, hepatic expression levels of Lgr5, Shp and Bsep were determined by QRT-PCR analysis. n = 5 per group. (E) Mice were orally treated with either vehicle or GW4064 (50 mg/kg) 2 days of twice-daily routines in a row. Then, hepatic expression levels of Lgr5, Shp and Bsep were determined by QRT-PCR analysis. n = 6 per group. (F) Representative images from RNAscope® ISH assays for Lgr5 and Gs on mouse liver cryosections treated with vehicle or CDCA. Red signal represents Lgr5, white represents Gs, blue shows DAPI. Scale bars, 20 µm. (G) ISH for Lgr5 combined with IF for Gs was performed on mouse liver paraffin sections treated with vehicle or GW4064. Red signal represents Lgr5, white represents Gs, blue shows DAPI. Scale bars, 50 µm. (H-I) Quantification of the IOD for (F-G) was presented in the corresponding diagram. Gene expression level of the samples normalized to internal control and the average expression of interest genes in vehicle group was set as 1. Data were expressed as means ± SD, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 were determined by the two-tailed Student's t-test.

Pharmacological activation of PPARα suppresses Lgr5 expression. (A-C) QRT-PCR analysis of PPARα, Cpt1a and Lgr5 expression in primary hepatocytes, Hep 1-6 cells and Hep G2 cells treated with GW7647 (10 µM) or DMSO for 24 h. n = 3 per group. (D) Mice were orally treated with vehicle or GW7647 (5 mg/kg) 2 days of twice-daily routines in a row. Then, hepatic expression levels of Lgr5, Cpt1a and Acox1 were determined by QRT-PCR analysis. n = 5 per group. (E) Mice were orally treated with vehicle or Wy14643 (100 mg/kg) 2 days of twice-daily routines in a row. Then, hepatic expression levels of Lgr5, Cpt1a and Acox1 were determined by QRT-PCR analysis. n = 4-5 per group. (F) Representative images from RNAscope® ISH assays for Lgr5 and Gs on mouse liver cryosections treated with vehicle or GW7647. Red signal represents Lgr5, white represents Gs, blue shows DAPI. Scale bars, 20 µm. (G) ISH for Lgr5 combined with IF for Gs was performed on mouse liver paraffin sections treated with vehicle or Wy14643. Red signal represents Lgr5, white represents Gs, blue shows DAPI. Scale bars, 50 µm. (H-I) Quantification of the IOD for (F-G) was presented in the corresponding diagram. Gene expression level of samples normalized to internal control and the average expression of genes in control group was set as 1. Data were expressed as means ± SD, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 were determined by the two-tailed Student's t-test.

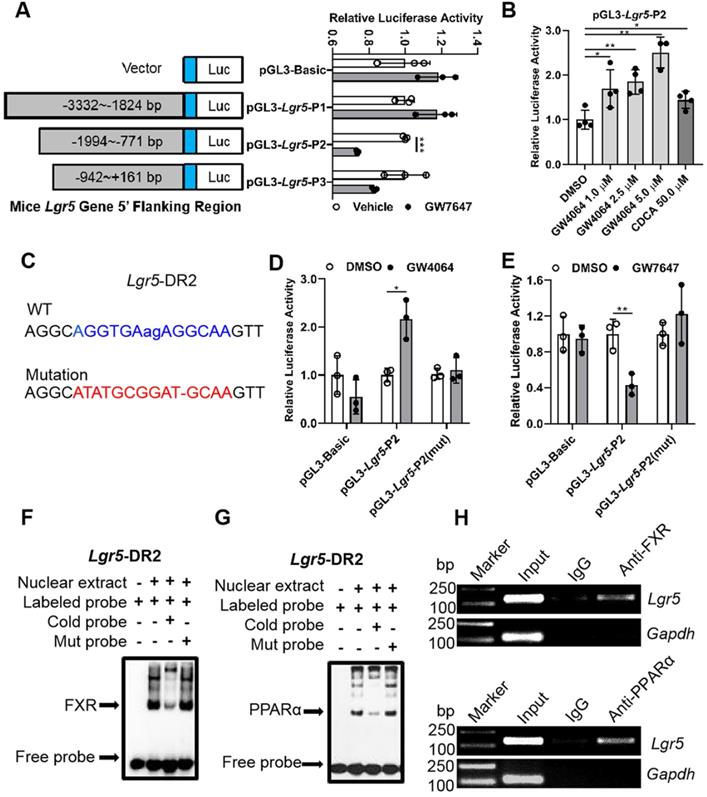

Promoter of Lgr5 contains putative FXR and PPARα binding site. (A) Amplification and activity detection of different fragments of Lgr5 promoter (position -3332 to -1824, -1994 to -771, -942 to +161 relative to the transcription start site). These fragments were inserted into the pGL3-Basic vector and transfected into Hep G2 cells with PPARα, RXR expression plasmids and pRL-TK using lipofectamine 2000. PPARα ligand GW7647 was added to cells for 24 h before the reporter assay. (B) Relative luciferase activity of the Lgr5-promoter reporter constructs when co-transfected into Hep G2 cells with FXR and RXRα expression plasmids and exposed to the indicated ligands. (C) Sequences of the WT and mutant Lgr5-DR2 sites. DR, direct repeat. 2, refers to the classical binding site separated by 2 bases (“ag” in lower case and highlighted in blue). “-” means base deletion. The blue DR2 nucleotides that were altered to form the mutant construct are marked red including “-”. (D-E) Lgr5-promoter or Lgr5-mutation plasmid was co-transfected into Hep 1-6 cells with pRL-TK. After incubation for 6 h, the cells were treated with DMSO, GW4064 or GW7647 for 24 h, respectively, and samples were analyzed by dual-luciferase assays. n = 3 per group. The ratio of firefly luciferase activity to renilla luciferase activity in control group was set to 1. (F-G) EMSA was performed to investigate the binding of liver nuclear proteins to the DR2. The position of the shifted NR/DR2 complex and free probes are indicated by arrows. (H) ChIP analysis showed that FXR or PPARα interacted with DR2 elements in Hep 1-6 cells treated with GW4064 or GW7647. Data were expressed as means ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments containing 3 replicates, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 were determined by the two-tailed Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA.

Nuclear receptor FXR and PPARα regulate Lgr5 transcriptional activation by binding to direct repeat (DR2) site on Lgr5 promoter

In general, nuclear receptors activate or repress target gene expression by directly binding to DNA response elements. In order to reveal the impact of both FXR and PPARα on Lgr5, luciferase assay kit was used to screen the most possible binding site. Results indicated that GW4064 promoted FXR binding to peaks corresponding to Lgr5 to increase its transcription. On the contrary, GW7647 treatment suppressed Lgr5 transcriptional activity (Figure 3A-B). Next, we carried out site-directed mutagenesis of the binding element, which abolished the reporter expression regulated by FXR and PPARα activation (Figure 3C-E). These results indicate that Lgr5 may be directly regulated by FXR and PPARα via binding to DR2 site.

EMSA results showed that the interaction between labeled probe and the nuclear extracts of mouse liver samples treated with GW4064 or GW7647 exhibited a DNA-protein band shift with expected mobility rate. Such an interaction was competitively inhibited by adding excessive unlabeled probes, rather than by adding mutation probes (Figure 3F-G). Subsequently, the specific precipitated elements were obtained by ChIP, indicating that FXR and PPARα could specifically interact with DR2 site, which was consistent with the above results (Figure 3H). Additionally, we combined different doses of the ligands to activate FXR and PPARα simultaneously, and the upregulation of Lgr5 suggested a dominant effect of FXR on Lgr5 regulation under the current conditions (Figure S4A-B). In addition, NCOR and NCOR2 are the most studied PPARα corepressors [33-35]. ChIP-PCR results showed that GW7647 increased NCOR and NCOR2 corepressors binding to the same DR2 element (Figure S4C), this might be why PPARα activation inhibits Lgr5 expression. Collectively, the above results suggest that FXR and PPARα mutually competed for binding to the same promoter element of Lgr5, but they drive opposite transcriptional outputs.

Activation of FXR or PPARα alters Lgr5 expression and Lgr5+ cell proliferation after DDC diets

We further investigated effects of FXR and PPARα on Lgr5+ cells-supported recovery from DDC-induced liver damage. Hematoxylin-eosin staining results indicated that ductular reaction and inflammatory infiltration were observed in all the mouse livers after 1 wk DDC treatment (Figure S5A). We also observed that FXR and PPARα activation rescued liver injury by attenuating plasma AST and ALT levels in WT mice fed with DDC diet (Figure S5B-C). For morphometric analysis, the bile duct was marked by CK19 and normalized to the area of portal veins showing significantly increased CK19-positive area/portal field in DDC-fed mice, which was accompanied by the development of portal-portal septa and the increasing TNFα mRNA levels (Figure S5D-H). In summary, DDC-fed WT mice exhibited pronounced symptoms of liver injury such as bile duct hyperplasia and focal necrosis, and these symptoms were relieved by FXR and PPARα activation.

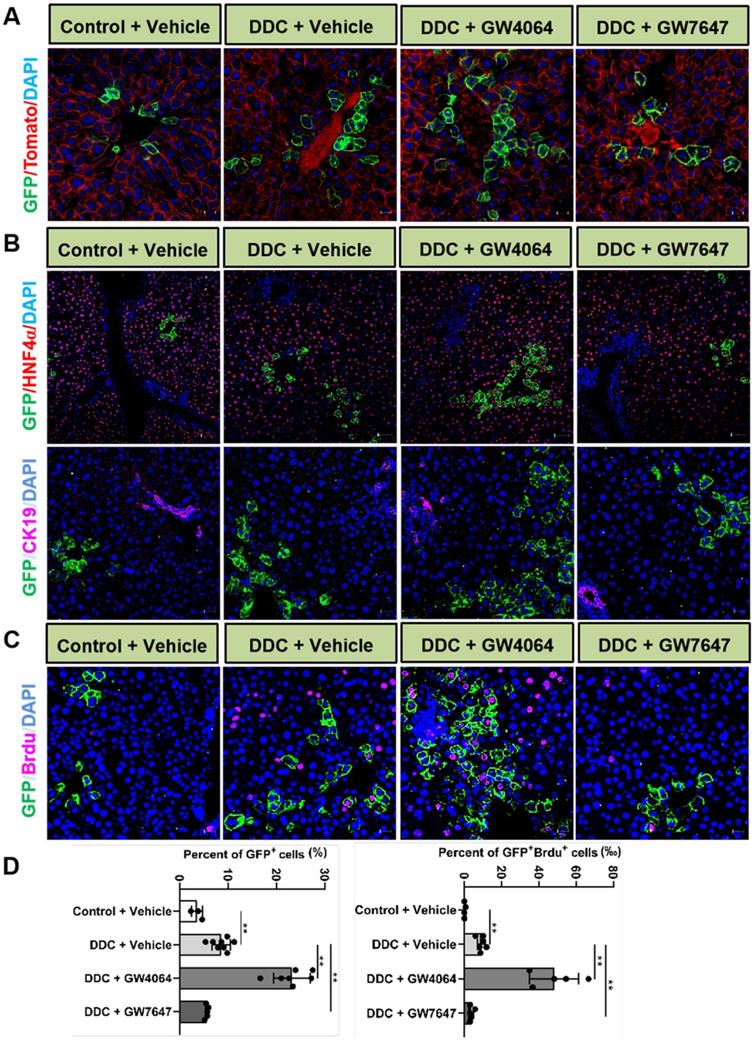

To further reveal the effects of FXR and PPARα activation on the cell fate of Lgr5, Lgr5-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG heterozygous mice were treated with DDC diet along with GW4064 or GW7647. We found that FXR activation promoted the expansion of Lgr5+ cells and their progeny in the PV region, while PPARα inhibited the expansion of Lgr5+ cells and their progeny (Figure 4A). Co-staining results of GFP with HNF4α or CK19 antibody revealed that GFP+ cells existed in the hepatocytes rather than in bile duct cells (Figure 4B). In addition, few GFP+ cells were labeled with BrdU in the control group. Upon DDC injury, BrdU incorporation was enhanced with an increasing number of GFP+ cells, and FXR activation further increased ratio of GFP+BrdU+ cells from 9.17‰ to 44.19‰, and the GFP+ cells migrated distally, away from PV to PP, whereas PPARα activation maintained the quiescence of Lgr5+ cells and their offspring (Figure 4C-D). The number of EdU positive cells at 24 h after EdU injection was significantly more than that of at the 4 h after EdU injection in DDC diet mice liver samples (Figure S6A-B). As illustrated in Figure S6C, nearly all EdU-labeled cells co-localized with BrdU-positive cells, these data suggest that EdU and BrdU staining methods detected DNA synthesis with equal efficiency. Based on these results, we conclude that EdU/BrdU+GFP+ cells are the result of daughter cell proliferation.

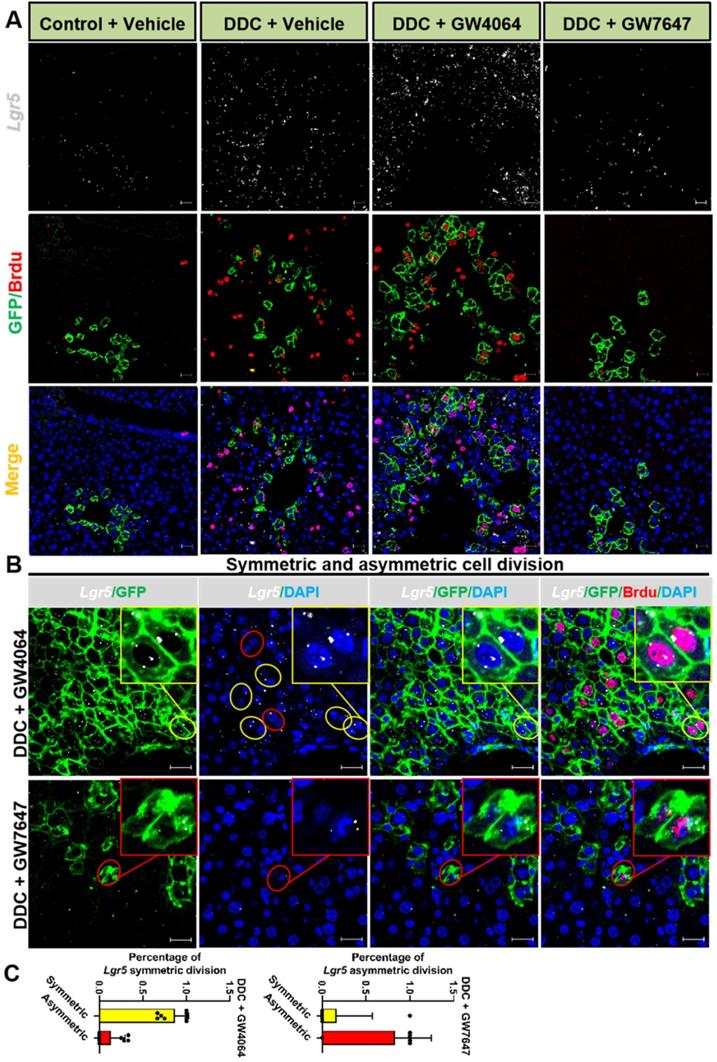

Previous study has reported that although multiple adult stem cells are likely to divide asymmetrically under homeostasis, they still have the ability to divide symmetrically to replenish the stem-cell pool whose exhaustion was caused by injury or disease [36]. Therefore, we examined whether FXR and PPARα had influence on liver injury repair via cell division of Lgr5+ cells. The co-staining results of Lgr5 probe, GFP antibody, and BrdU antibody indicated that FXR activation promoted Lgr5+ cells proliferation mainly by symmetric cell divisions to generate more stem cells with Lgr5 expression (Figure 5A-C and Figure S7A). On the contrary, PPARα activation preferentially inhibited Lgr5 cells proliferation by asymmetric cell division to maintain self-renewal or static state (Figure 5B-C and Figure S7A). Furthermore, ISH for Lgr5 combined with IF for BrdU and β-actin multiple fluorochrome labeled antibody hybridization were performed to test Lgr5 expression and Lgr5+ stem cell proliferation. DDC-injured GW4064 treated mouse liver exhibited symmetric cell division with both of the daughter cells expressing Lgr5, while GW7647 treated group showed asymmetric cell division with one stem cell expressing Lgr5 and one differentiated cell without Lgr5 expression (Figure S7B-C).

Taken together, FXR and PPARα oppositely regulate cell fate of Lgr5+ and their offspring under hepatic physiological and pathological conditions.

Activation of FXR or PPARα alters Lgr5 expression and Lgr5+ cells propagation after DDC diets. Liver sections of Lgr5-CreERT2; Rosa26-mTmG mice treated with tamoxifen (100 mg/kg) were analyzed. Mice were fed with DDC diet for 1 wk and treated with GW4064 or GW7647. (A) Representative images from fixed frozen liver sections showing lineage tracking of Lgr5 cells upon DDC damage. GFP (green) fluorescence shows Lgr5+ hepatocytes and the offspring. Tomato fluorescence shows Lgr5- hepatocytes. Scale bars, 20 µm. (B) Representative images showing tracking of Lgr5 cells upon DDC damage. Co-staining results of GFP (Green) with HNF4α (Red, scale bars, 50 µm) or CK19 (Violet, scale bars, 20 µm). (C) GFP and BrdU double staining livers after DDC injury. Blue (DAPI) shows nuclei, violet (BrdU) marks the proliferating cells, green represents Lgr5+ cells and their offspring cells. Scale bar represents 20 µm. (D) Graphs showing percentages of GFP+ cell and GFP+ BrdU+ cell in the indicated groups. Data were expressed as means ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments containing 4 replicates, **p < 0.01 were determined by one-way ANOVA.

Lgr5+ cells predominately undergo symmetric division while FXR activation but turn on asymmetric division while PPARα activation. (A) ISH for Lgr5 combined with IF for GFP and BrdU was performed to confirm Lgr5 expression and Lgr5+ stem cell proliferation. (B) Yellow circle depicts the symmetric division, both of the daughter cells with Lgr5 expression, and red circle depicts the asymmetric division, the stem cell with Lgr5 expression (white) and another daughter cell without Lgr5 expression. Scale bar represents 20 µm. (C) Quantification of Lgr5 symmetric or asymmetric division in GFP+ liver stem cell maintained in livers. n = 3 per group. Data were expressed as means ± SD.

Discussion

Although Lgr5+ cells have been reported to be beneficial for liver damage repair [5], the expression of Lgr5 in the liver has been controversial. Some research indicates that Lgr5 only appears near bile ducts after liver damage [5], but other research reveals that Lgr5 is expressed in normal adult liver [31, 32, 37]. Unfortunately, the previous studies failed to accurately mimic the expression pattern of endogenous Lgr5 due to the single detection method. In this study, combining WB, IF, RNAscope® ISH and lineage tracing, we reproduced that Lgr5 was expressed in normal liver and Lgr5+ cells were located in the PV area. Previous research indicates that β-catenin signal is activated in all of the PV hepatocytes [38]. Since Lgr5 was a downstream target gene of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, our results that Lgr5 was located around PV area were consistent with those from the point of view of metabolic zoning and anatomical localization [39, 40].

Metabolic nuclear receptors have been found to regulate the fate of Lgr5+ stem cells in the intestinal tract through Wnt pathway and diet [11, 41]. However, whether nuclear receptors can regulate the fate of Lgr5 hepatocytes during liver regeneration and repair has not been documented. FXR and PPARα are essential regulators of metabolic responses and highly expressed in hepatocytes [42, 43]. FXR is activated by endogenous BA synthesized from cholesterol in the PV hepatocytes. PPARα is up-regulated at PP area with high oxygen concentration, thus intrinsically raising key biological and metabolic activity [44, 45]. In this study, we found that activation of FXR promoted Lgr5 expression and activation of PPARα inhibited Lgr5 expression both in vitro and in vivo. Previous research has also indicated that FXR and PPARα coordinate autophagy by directly competing for occupancy at the same site on autophagy-related gene promoter [20]. Consistent with their results, our data showed that FXR and PPARα exhibited opposite regulatory effects on Lgr5 transcription by directly binding to the shared promoter element (DR2). Moreover, FXR and PPARα function coordinately to control pivotal nutrient pathways and to maintain liver energy balance and that may alter liver stem cell fate [46]. After a meal, hepatic FXR is activated by the BA that return to the liver [46] and it may affect Lgr5 stem cell behavior. Meanwhile, dietary treatment with bile acid cholic acid reportedly inhibited primary PPARα targets, such as Acox1, which may downregulate fatty acid oxidation levels [46] and result in hindering Lgr5+ stem cell expansion. These effects are consistent with their expected roles as mediators of the feeding and fasted responses and are in agreement with our results that a dominant effect on Lgr5 regulation by FXR under physiological conditions. Previous study has reported that high expression of Lgr5 is observed in chronic liver disease, and that Lgr5+ liver cells probably contribute to liver function recovery [6]. Notably, the dynamics of Lgr5 expression post damage suggest that Lgr5 should be expressed in the early stage of the injury initiation and it should be switched off once the tissue regeneration is finished. Based on these findings, it could be speculated that Lgr5 might act as a switch for cell proliferation [47]. Accordingly, this study proposed a local expansion manner of hepatocytes in liver homeostasis and regeneration. Lineage tracing results have shown that Lgr5+ cells in mice fed with normal diet maintained static state, that DDC diet triggered the transition of Lgr5+ cells from a resting state to a proliferating state, and that activation of FXR or PPARα altered Lgr5+ liver stem cell propagation, thus alleviating liver injury after DDC diet. This result is in line with the previous conclusion that FXR and PPARα can promote liver regeneration and repair [48-50]. Our data indicated that during liver injury repair, FXR activation drove the expansion of Lgr5+ cells around the PV region, and PPARα had opposite effects. On one hand, the co-regulation of Lgr5 by FXR and PPARα promoted the rapid proliferation of Lgr5+ cells upon injury, on the other hand, co-regulation could prevent the excessive proliferation of Lgr5+ cells and their progeny, which might explain the mechanism of initiation and termination of liver regeneration to some degree. Thus, Lgr5 could mark those cells that exhibited high plasticity and could freely switching between stem cells and differentiation cells. Additionally, upon DDC injury, GW4064 or GW7647-treated mice exhibited some Lgr5-/BrdU+ or GFP-/BrdU+ cells, these should also be taken into consideration. The liver with alternative stem cell niches exhibited strong adaptability to maintain a dynamic balance after chronic liver injury. And based on our previous research, specific FXR agonists given orally can activate intestinal FXR, which may regulate hepatocyte proliferation though FXR-FGF15-BA axis should also be taken into consideration [13]. Beyond that, activation of intestinal FXR shaped the gut microbiota to activate TGR5/GLP-1 signaling to improve liver function [51]. More investigation needs to carry out to show how intestine FXR activation contributes to the liver regeneration during chronic liver injury.

There are two types of cell division to ensure the self-renewal of mammalian stem cells in the process of proliferation. Asymmetrical cell division produces one stem cell and one differentiation cell to balance stem cell numbers for homeostasis maintenance, while symmetrical cell division generates two daughter stem cells to enlarge the stem cell pool for tissue regeneration [52, 53]. Herein, we found that FXR promoted the symmetric cell division of Lgr5+ cells for liver regeneration, and PPARα tended to induce asymmetric division of Lgr5+ cells and their offspring for self-renewal or quiescence maintenance. The symmetrical division ability of stem cells enhanced tissue developmental plasticity and liver regeneration capacity, but over-proliferation might cause cancer, and PPARα activation could effectively resist cancer risk. Thus, we proposed that the switch between symmetric and asymmetric divisions of Lgr5 stem cells was regulated by FXR and PPARα activation. This regulatory switch is closely associated with basic stem-cell biology, and has great significance to the clinical application of stem cells.

Conclusions

In generally, our results reveal intersecting and complementary genomic circuits in which nuclear receptors induced or suppressed Lgr5 expression. Our research also illustrates FXR and PPARα may be potential drug targets for liver diseases since they can regulate Lgr5+ cells fate. This study provides useful information for maintaining homeostasis of liver, and it will be of great significance for exploring the pathogenesis mechanism of human diseases and therapeutic strategies.

Abbreviations

Acox1: acyl-CoA oxidase1; BA: bile acid; Bsep: bile salt export pump; ChIP: Chromatin immunoprecipitation; Ck19: Cytokeratin 19; Cpt1a: Carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1a; DDC: diethyl1,4-dihydro-2,4,6-trimethyl-3,5-pyridinedicarboxylate; EMSA: electrophoretic mobility shift assay; FXR: farnesoid X receptor; GFP: green fluorescence; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; Hnf4α: hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α; IF: immunofluorescence; ISH: in situ hybridization; KO: knockout; Lgr5: leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 5; PP: periportal; PPARα: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α; PV: perivenous; Shp: small heterodimer partner; WT: wild-type; wk: week.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Jun Li and Yuansen Zhai for their expert technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32071143) and National Key R&D Plan no. 2017YFA0103202, and Huazhong Agricultural University Startup Funds to Lisheng Zhang.

Author contributions

Lisheng Zhang and Dan Qin conceived and designed the study. Dan Qin provided the experimental data. Dan Qin, Shenghui Liu and Yuanyuan Lu performed the cell and animal experiments. Jing Zhang, Shiyao Cao, Mi Chen and Ning Chen provided assistance in molecular assays. Dan Qin, Shenghui Liu, and Yi Yan discussed and drafted the manuscript. Wendong Huang, Liqiang Wang and Xiangmei Chen revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Lisheng Zhang supervised the project, organized the data and finally approval of the version to be submitted.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Supplementary figures and tables can be found in Supplementary Information.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Zhang Z, Wang FS. Stem cell therapies for liver failure and cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):183-5

2. Michalopoulos G, Bhushan B. Liver regeneration: biological and pathological mechanisms and implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(1):40-55

3. Fracanzani AL, Taioli E, Sampietro M, Fatta E, Fargion S. Liver cancer risk is increased in patients with porphyria cutanea tarda in comparison to matched control patients with chronic liver disease. J Hepatol. 2001;35(4):498-503

4. Barker N, Bartfeld S, Clevers H. Tissue-resident adult stem cell populations of rapidly self-renewing organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7(6):656-70

5. Huch M, Dorrell C, Boj S, van Es J, Li V, van de Wetering M. et al. In vitro expansion of single Lgr5+ liver stem cells induced by Wnt-driven regeneration. Nature. 2013;494(7436):247-50

6. Lin Y, Fang Z, Liu H, Wang L, Cheng Z, Tang N. et al. HGF/R-spondin1 rescues liver dysfunction through the induction of Lgr5 liver stem cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1175

7. Huch M, Gehart H, van Boxtel R, Hamer K, Blokzijl F, Verstegen M. et al. Long-term culture of genome-stable bipotent stem cells from adult human liver. Cell. 2015;160:299-312

8. Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, Wetering MVD, Snippert HJ, Es JHV. et al. Lgr5+ stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6(1):25-36

9. Lei ZJ, Wang J, Xiao HL, Guo Y, Wang T, Li Q. et al. Lysine-specific demethylase 1 promotes the stemness and chemoresistance of Lgr5+ liver cancer initiating cells by suppressing negative regulators of β-catenin signaling. Oncogene. 2015;34(24):3188

10. Cao W, Li M, Liu J, Zhang S, Pan Q. Lgr5 marks targetable tumor-initiating cells in mouse liver cancer. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1961

11. Fu T, Coulter S, Yoshihara E, Oh T, Fang S, Cayabyab F. et al. FXR regulates intestinal cancer stem cell proliferation. Cell. 2019;176(5):1098-112.e18

12. Sun L, Cai J, Gonzalez F. The role of farnesoid X receptor in metabolic diseases, and gastrointestinal and liver cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(5):335-47

13. Zhang L, Wang Y, Chen W, Wang X, Lou G, Liu N. et al. Promotion of liver regeneration/repair by farnesoid X receptor in both liver and intestine in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56(6):2336-43

14. Kim C, Ding X, Allmeroth K, Biggs L, Kolenc O, L'Hoest N. et al. Glutamine metabolism controls stem cell fate reversibility and long-term maintenance in the hair follicle. Cell Metab. 2020;32(4):629-42.e8

15. Massafra V, Milona A, Vos H, Ramos R, Gerrits J, Willemsen E. et al. Farnesoid x receptor activation promotes hepatic amino acid catabolism and ammonium clearance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(6):1462-76.e10

16. Pereira B, Amaral AL, Dias A, Mendes N, Muncan V, Silva AR. et al. Mex3a regulates Lgr5+ stem cell maintenance in the developing intestinal epithelium. EMBO Rep. 2020;21(4):e48938

17. Kandel B. Comparative analysis of the nuclear receptors CAR, PXR and PPARα in the regulation of hepatic energy homeostasis and xenobiotic metabolism. Polit Commun. 2014;36(4):203-4

18. Nakagawa K, Tanaka N, Morita M, Sugioka A, Miyagawa S, Gonzalez F. et al. PPARα is down-regulated following liver transplantation in mice. J Hepatol. 2012;56(3):586-94

19. Mihaylova M, Cheng C, Cao A, Tripathi S, Mana M, Bauer-Rowe K. et al. Fasting activates fatty acid oxidation to enhance intestinal stem cell function during homeostasis and aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(5):769-78.e4

20. Lee J, Wagner M, Xiao R, Kim K, Feng D, Lazar M. et al. Nutrient-sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature. 2014;516(7529):112-5

21. Xu Z, Huang G, Gong W, Zhou P, Zhao Y, Zhang Y. et al. FXR ligands protect against hepatocellular inflammation via SOCS3 induction. Cell Signal. 2012;24(8):1658-64

22. Fickert P, Stöger U, Fuchsbichler A, Moustafa T, Marschall H, Weiglein A. et al. A new xenobiotic-induced mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(2):525-36

23. Taniai H, Hines IN, Bharwani S, Maloney RE, Aw TY. Susceptibility of murine periportal hepatocytes to hypoxia-reoxygenation: role for NO and kupffer cell-derived oxidants. Hepatology. 2004;39(6):1544-52

24. Zhang Q, He F, Kuruba R, Gao X, Wilson A, Li J. et al. FXR-mediated regulation of angiotensin type 2 receptor expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77(3):560-9

25. Yan F, Wang Q, Lu M, Chen W, Song Y, Jing F. et al. Thyrotropin increases hepatic triglyceride content through upregulation of SREBP-1c activity. J Hepatol. 2014;61(6):1358-64

26. Maloney P, Parks D, Haffner C, Fivush A, Chandra G, Plunket K. et al. Identification of a chemical tool for the orphan nuclear receptor FXR. J Med Chem. 2000;43(16):2971-4

27. Brown P, Stuart L, Hurley K, Lewis M, Winegar D, Wilson J. et al. Identification of a subtype selective human PPARalpha agonist through parallel-array synthesis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11(9):1225-7

28. Nagrath D, Xu H, Tanimura Y, Zuo R, Berthiaume F, Avila M. et al. Metabolic preconditioning of donor organs: defatting fatty livers by normothermic perfusion ex vivo. Metab Eng. 2009;11(4-5):274-83

29. Karamichos D, Hutcheon AEK, Zieske JD. Transforming growth factor-β3 regulates assembly of a non-fibrotic matrix in a 3D corneal model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5(8):e228-e38

30. Sun T, Pikiolek M, Orsini V, Bergling S, Tchorz JS. Axin2+ pericentral hepatocytes have limited contributions to liver homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;26(1):97-107.e6

31. Ang CH, Hsu SH, Guo F, Tan CT, Yu VC, Visvader JE. et al. Lgr5(+) pericentral hepatocytes are self-maintained in normal liver regeneration and susceptible to hepatocarcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(39):19530-40

32. Planas-Paz L, Orsini V, Boulter L, Calabrese D, Pikiolek M, Nigsch F. et al. The Rspo-Lgr4/5-Znf3/Rnf43 module controls liver zonation and size. Nat Cell Biol. 2016;18(5):467-79

33. Oberoi J, Fairall L, Watson PJ, Yang JC, Czimmerer Z, Kampmann T. et al. Structural basis for the assembly of the SMRT/NCoR core transcriptional repression machinery. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(2):177-84

34. Mottis A, Mouchiroud L, Auwerx J. Emerging roles of the corepressors NCoR1 and SMRT in homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2013;27(8):819-35

35. Kang Z, Fan R. PPARα and NCOR/SMRT corepressor network in liver metabolic regulation. FASEB J. 2020;34(7):8796-809

36. Yamashita Y, Yuan H, Cheng J, Hunt A. Polarity in stem cell division: asymmetric stem cell division in tissue homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(1):a001313

37. Braeuning A, Ittrich C, Köhle C, Hailfinger S, Bonin M, Buchmann A. et al. Differential gene expression in periportal and perivenous mouse hepatocytes. FEBS J. 2010;273(22):5051-61

38. Benhamouche S, Decaens T, Godard C, Chambrey R, Rickman D, Moinard C. et al. Apc tumor suppressor gene is the "zonation-keeper" of mouse liver. Dev Cell. 2006;10(6):759-70

39. Zhan T, Rindtorff N, Boutros M. Wnt signaling in cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36(11):1461-73

40. Halpern KB, Shenhav R, Matcovitch-Natan O, Toth B, Lemze D, Golan M. et al. Single-cell spatial reconstruction reveals global division of labour in the mammalian liver. Nature. 2017;542(7641):352-6

41. Beyaz S, Mana MD, Roper J, Kedrin D, Saadatpour A, Hong SJ. et al. High-fat diet enhances stemness and tumorigenicity of intestinal progenitors. Nature. 2016;531(7592):53-8

42. Han C, Rho H, Kim A, Kim T, Jang K, Jun D. et al. FXR inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced Nlrp3 inflammasome in hepatocytes and ameliorates liver injury. Cell Rep. 2018;24(11):2985-99

43. Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, M D, Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137(1):354-6

44. Keller H, Dreyer C, Medin J, Mahfoudi A, Ozato K, Wahli W. Fatty acids and retinoids control lipid metabolism through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-retinoid X receptor heterodimers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(6):2160-4

45. Ma K, Saha P, Chan L, Moore DD. Farnesoid X receptor is essential for normal glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(4):1102-9

46. Preidis GA, Kang HK, Moore DD. Nutrient-sensing nuclear receptors PPARα and FXR control liver energy balance. J Clin Invest. 2017;127(4):1193-201

47. Huch M, Dollé L. The plastic cellular states of liver cells: Are EpCAM and Lgr5 fit for purpose? Hepatology. 2016;64(2):652-62

48. Huang W, Ma K, Zhang J, Qatanani M, Cuvillier J, Liu J. et al. Nuclear receptor-dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science. 2006;312(5771):233-6

49. Anderson S, Yoon L, Richard E, Dunn C, Cattley R, Corton J. Delayed liver regeneration in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha-null mice. Hepatology. 2002;36(3):544-54

50. Cai PC, Mao XY, Zhao JQ, Nie L, Jiang Y, Yang QF. et al. Farnesoid x receptor is required for the redifferentiation of bi-potential progenitor cells during biliary-mediated zebrafish liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2021;74(6):3345-61

51. Pathak P, Xie C, Nichols R, Ferrell J, Boehme S, Krausz K. et al. Intestine farnesoid X receptor agonist and the gut microbiota activate G-protein bile acid receptor-1 signaling to improve metabolism. Hepatology. 2018;68(4):1574-88

52. Ohlstein B, Spradling A. Multipotent drosophila intestinal stem cells specify daughter cell fates by differential Notch signaling. Science. 2007;315(5814):988-92

53. Morrison SJ, Kimble J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 2006;441(7097):1068-74

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Lisheng Zhang, PhD, College of Veterinary Medicine/College of Biomedicine and Health, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, Hubei, 430070, China. E-mail: lishengzhanghzau.edu.cn. Tel./fax: +862787282091.

Corresponding author: Lisheng Zhang, PhD, College of Veterinary Medicine/College of Biomedicine and Health, Huazhong Agricultural University, Wuhan, Hubei, 430070, China. E-mail: lishengzhanghzau.edu.cn. Tel./fax: +862787282091.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact