13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2018; 8(14):3751-3765. doi:10.7150/thno.22493 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Identification and Functional Characterization of Long Non-coding RNA MIR22HG as a Tumor Suppressor for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

1. Department of Radiation Oncology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

2. State Key Laboratory of Organ Failure Research, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

3. Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Viral Hepatitis Research, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

4. Department of Infectious Diseases, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

5. Department of General Surgery, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China

† These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2017-8-23; Accepted 2018-1-16; Published 2018-6-13

Abstract

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have recently been identified as critical regulators in tumor initiation and development. However, the function of lncRNAs in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains largely unknown. Our study was designed to explore the biological function and clinical implication of lncRNA MIR22HG in HCC.

Methods: We evaluated MIR22HG expression in 52-patient, 145-patient, TCGA, and GSE14520 HCC cohorts. The effects of MIR22HG on HCC were analyzed in terms of proliferation, invasion, and metastasis, both in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism of MIR22HG action was explored through bioinformatics, luciferase reporter, and RNA immunoprecipitation analyses.

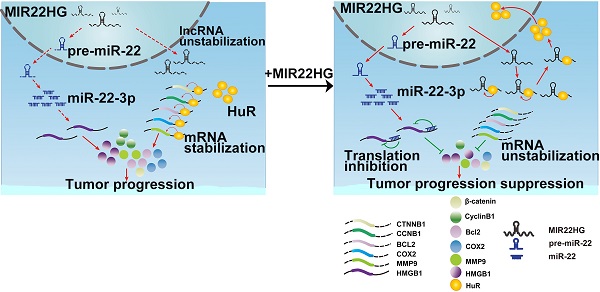

Results: MIR22HG expression was significantly down-regulated in 4 independent HCC cohorts compared to that in controls. Its low expression was associated with tumor progression and poor prognosis of patients with HCC. Forced expression of MIR22HG in HCC cells significantly suppressed proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, MIR22HG derived miR-22-3p to target high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), thereby inactivating HMGB1 downstream pathways. Additionally, MIR22HG directly interacted with HuR and regulated its subcellular localization. MIR22HG competitively bound to human antigen R (HuR), resulting in weakened expression of HuR-stabilized oncogenes, such as β-catenin. Furthermore, miR-22-3p suppression, HuR or HMGB1 overexpression rescued the inhibitory effects caused by MIR22HG overexpression.

Conclusion: Our findings revealed that MIR22HG plays a key role in tumor progression by suppressing the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells, suggesting its potential role as a tumor suppressor and prognostic biomarker in HCC.

Keywords: liver cancer, miR-22 host gene, HuR, tumor suppressor, prognostic factor

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly lethal cancer that has exhibited a steady rise in incidence, especially in East Asia and South Africa [1]. Despite improvements in liver transplantation, surgical resection, and molecular-targeted therapy, the prognosis of HCC has remained poor over the last decades [2, 3]. The highly invasive and metastatic nature of HCC cells leads to early hepatic metastasis and portal vein tumor thrombus (PVTT), thus hampering thorough tumor removal and potentially representing a key factor for poor prognosis [4, 5]. Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular basis underlying invasion and metastasis is critical to identify efficacious therapeutic targets.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) critically participate in various physiological processes, with their dysregulation associated with multiple human diseases, including cancers [6-8]. Although previous studies have reported the roles and general underlying mechanisms of lncRNAs in HCC, their specific mechanisms associated with HCC initiation and progression still require elucidation [9]. In our previous study, we examined genome-wide lncRNA expression profiles (Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) Series Accession Number GSE58043) in HCC tissues and paired adjacent non-tumor tissues [10]. From this analysis, we noted that lncRNA NR_028502.1 located in 17p13.3, a chromosomal region that is frequently deleted, hypermethylated, or shows loss of heterozygosity in liver cancer, was down-regulated in HCC [11, 12]. NR_028502.1 is identified as a lncRNA in The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project and was annotated as the human miR-22 host gene (MIR22HG). However, the biological function of MIR22HG has not been studied.

Chromosome location and sequence similarity suggest that some lncRNAs might serve as the host genes of miRNAs and act in close association with miRNAs [13]. For example, lncRNA H19, a host gene of miR-675, generates mature miR-675-5p and miR-675-3p that are involved in tumor metastasis [14-16]. miR-31 is transcribed from lncRNA LOC554202, with both shown to be down-regulated in triple-negative breast cancer [17]. However, in some cases, although a lncRNA might serve as the host gene of an miRNA, these molecules act independently of each other, as observed for miR-1207-5p and its host in diabetic nephropathy [18]. However, correlations between the host gene MIR22HG and miR-22-3p in human HCC remain unknown.

In this study, we examined the expression of MIR22HG in HCC tissues and found that it was expressed at low levels in HCC and associated with prognosis in patients with HCC. Additionally, we assessed the biological roles of MIR22HG in HCC both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, our findings revealed that MIR22HG not only derived miR-22-3p to inhibit tumor progression but also specifically interacted with human antigen R (HuR) to increase MIR22HG stability, promote HuR translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, and decrease the binding abilities of HuR with oncogene mRNAs such as for CTNNB1(encoding β-catenin), CCNB1 (encoding cyclinB1), HIF1A (encoding hypoxia-inducible factor -1α), BCL2 (encoding apoptosis regulator Bcl2), COX2 (encoding cyclooxygenase COX2), and C-FOS (encoding a nuclear phospho-protein c-Fos). Therefore, our study provides a novel understanding of lncRNA in HCC and suggests lncRNAs as potential cancer biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

Results

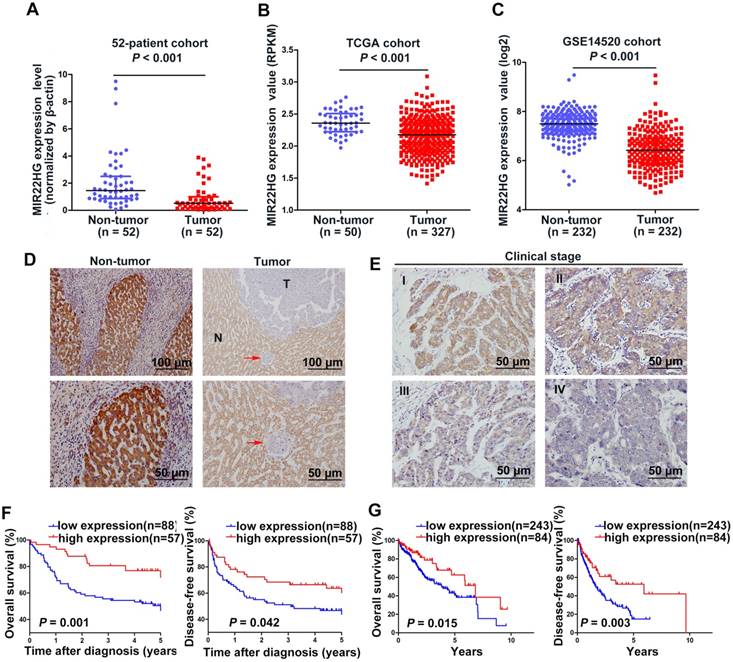

MIR22HG Expression is Downregulated in HCC Tissues

Our previous microarray analysis indicated that MIR22HG was expressed at low levels in HCC tissues as compared with non-tumor tissues (P = 0.016) [10]. Human MIR22HG consists of 4 transcripts (variants 1-4, Figure S1A). We detected the expression of these 4 transcripts in 7 paired HCC tissues and corresponding non-tumor tissues, and found that variant 1 was the most abundant isoform in non-tumor tissues, but was dramatically downregulated in tumor tissues (Figure S1B). Therefore, we focused on variant 1 to obtain further insight into MIR22HG. We then assayed MIR22HG expression in 52 pairs of HCC tissues and matched non-tumor tissues (52-patient cohort) by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), finding that MIR22HG was significantly downregulated in HCC (P < 0.001; Figure 1A). Furthermore, expression data from two independent HCC cohorts (The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and GEO accession number GSE14520) were employed for validation. Statistical analysis showed that MIR22HG expression was also decreased in HCC tissues in these two cohorts (P < 0.001 for both cohorts; Figure 1B, 1C). These findings confirmed that MIR22HG was consistently downregulated in HCC.

Low Expression of MIR22HG Correlates with Tumor Progression and Poor Prognosis in Human HCC

To assess the clinical significance of MIR22HG expression, we performed in situ hybridization (ISH) on 145 human HCC tissues. The ISH assay showed that MR22HG was expressed at low levels in HCC and mainly located in the cytoplasm (Figure 1D, 1E). Low MR22HG expression strongly correlated with poor pathological grade (P = 0.004), PVTT (P = 0.004), and advanced clinical stage (P = 0.005), indicating that MIR22HG was negatively correlated with the clinical progression of HCC (Table S3).

MIR22HG expression is down-regulated in HCC and is correlated with prognosis. (A) Expression level of MIR22HG in HCC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues (52-patient cohort) as measured by qRT-PCR analysis (P < 0.001); β-actin was used as an internal control. Data are shown as median with interquartile range. (B-C) Expression of MIR22HG in the TCGA and GSE14520 cohorts (P < 0.001). (D) Expression of MIR22HG in patients with HCC (145-patient cohort) detected by ISH. Representative images of non-tumor (N) and tumor (T) tissues are shown. The red arrow indicates microvascular tumor. (E) MIR22HG expression is correlated with clinical stage. Representative images of clinical stages I to IV are shown. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the overall and disease-free survival (log-rank) in the 145-patient cohort based on MIR22HG expression. (G) Kaplan-Meier analysis of the overall and disease-free survival in the TCGA cohort based on MIR22HG expression.

Survival analysis of the 145-patient cohort showed that patients with HCC and high MIR22HG expression exhibited better overall survival (OS; P = 0.001) and disease-free survival (DFS; P = 0.042) as compared with those with low MIR22HG expression (Figure 1F). This finding was validated in the TCGA cohort (P = 0.015 for OS; P = 0.003 for DFS; Figure 1G). Furthermore, univariate Cox regression analysis revealed that the mortality risk of patients with HCC was significantly associated with low MIR22HG expression (95% CI: 0.227-0.735; P = 0.003), PVTT (95% CI: 2.008-6.578; P< 0.001), clinical stage (95% CI: 1.077-3.101; P = 0.025), tumor relapse (95% CI: 1.164-3.249; P = 0.011), and tumor size (95% CI: 1.123-3.308; P = 0.017) (Table 1). In multivariate analysis, lower MIR22HG expression emerged as an independent prognostic factor for OS in patients with HCC (95% CI: 0.270-0.912; P = 0.024; Table 1).

Univariate and multivariate analyses of OS in the 145-patient cohort by Cox regression analysis.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | CI (95%) | P value | HR | CI (95%) | P value | ||

| Gender | 1.232 | 0.653-2.324 | 0.519 | ||||

| Age (years) | 1.092 | 0.653-1.827 | 0.736 | ||||

| Edmondson Grade | 1.234 | 0.655-2.327 | 0.515 | ||||

| Metastasis (distant) | 1.922 | 0.696-5.308 | 0.208 | ||||

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.854 | 0.481-1.517 | 0.591 | ||||

| Tumor number | 1.215 | 0.656-2.250 | 0.535 | ||||

| Portal vein tumor thrombus | 3.634 | 2.008-6.578 | 0.000* | ||||

| BCLC stage | 1.827 | 1.077-3.101 | 0.025* | ||||

| Relapse | 1.945 | 1.164-3.249 | 0.011* | ||||

| Tumor size | 1.928 | 1.123-3.308 | 0.017* | ||||

| MIR22HG | 0.409 | 0.227-0.735 | 0.003* | 0.496 | 0.270-0.912 | 0.024* | |

BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard radio; OS: overall survival

*The values had statistically significant differences.

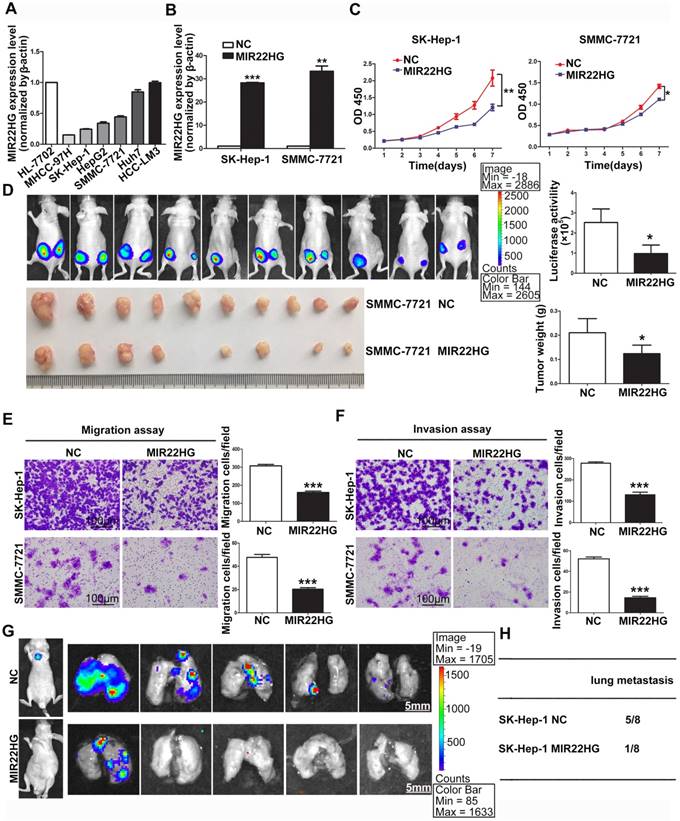

MIR22HG Overexpression Suppresses HCC Cell Proliferation, Invasion, and Metastasis In Vitro and In Vivo

MIR22HG overexpression suppresses proliferation, invasion, and metastasis in vitro and in vivo. (A) Expression of MIR22HG in the indicated HCC cell lines as determined by qRT-PCR analysis. The normal liver cell line HL-7702 was used as a control. (B) Human MIR22HG sequence was stably transduced into SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells by lentiviral vector. MIR22HG expression was detected by qRT-PCR. NC: negative control. (C) Cell proliferation was evaluated by the CCK-8 assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (D) Effect of MIR22HG overexpression in SMMC-7721 cells on tumor growth in vivo. A mouse HCC xenograft model was created as described in Materials and Methods. The volume and weight of subcutaneous xenograft tumors in the MIR22HG and control groups are indicated (n = 10). *P < 0.05. (E) Motility of SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells after transfection of lentivirus harboring either the full-length human MIR22HG sequence or the empty vector as evaluated by a migration assay. ***P < 0.0001. (F) Invasion ability of SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells after transfection of MIR22HG vector or the empty vector as determined by the Matrigel invasion assay. ***P < 0.0001. (G) MIR22HG-overexpressing SK-Hep-1 cells and control cells were injected intravenously into mice and bioluminescence images were obtained (n = 8). Representative images of pulmonary colonization at 6 weeks after injection are shown. (H) Numbers of mice with lung metastases in both groups.

Detection of MIR22HG expression in HCC cell lines indicated that MIR22HG was highly expressed in Huh7 and HCC-LM3 cells and poorly expressed in SK-Hep-1, SMMC-7721, HepG2, and MHCC-97H cells (Figure 2A). To evaluate the biological function of MIR22HG in HCC, the human MIR22HG sequence was introduced into SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells by lentiviral transduction for stable expression (Figure 2B). The results showed MIR22HG overexpression significantly reduced cell-proliferative capability (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the effect of MIR22HG overexpression on tumor growth in vivo was examined using mouse subcutaneous xenograft models. Tumor xenografts derived from MIR22HG-overexpressing SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells exhibited smaller volumes and lower weights than those from empty vector-transduced cells (Figure 2D and Figure S1C). Additionally, the positive rate of Ki-67, a marker of proliferation, was significantly reduced among MIR22HG-overexpressing cells (Figure S1D, S1E). These results demonstrated that MIR22HG inhibited HCC cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo.

Additionally, short-hairpin RNAs specifically targeting MIR22HG were introduced into HCC-LM3 cells to silence MIR22HG (Figure S2A), with the results indicating that MIR22HG deletion promoted cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo (Figure S2B, S2C). Moreover, the positive rate of Ki-67 was notably increased in MIR22HG-silenced HCC-LM3 cells. (Figure S2D).

The observation that low MIR22HG expression was significantly correlated with PVTT prompted us to examine whether MIR22HG might function as a suppressor of HCC-cell invasion and metastasis. Accordingly, both migration and invasion assays in vitro showed that MIR22HG upregulation dramatically decreased the mobility and invasiveness of SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells (P < 0.001; Figure 2E, 2F), whereas MIR22HG knockdown promoted the mobility and invasiveness of HCC-LM3 cells (Figure S3A). To confirm these data in vivo, MIR22HG-overexpressing SK-Hep-1 cells and MIR22HG-silenced HCC-LM3 cells were intravenously injected into nude mice via tail vein. As shown in Figure 2G, MIR22HG overexpression suppressed the metastasis of SK-Hep-1 cells to the lungs. In particular, at 6-weeks post-injection, 12.5% of mice (1/8) in the MIR22HG-overexpressing group exhibited lung metastasis as compared with 62.5% (5/8) in the mock-injected group (Figure 2H). Furthermore, metastatic foci were sparse and small in the MIR22HG-overexpressing group, whereas multiple metastases of different sizes were found in the control group. Statistical analysis indicated that MIR22HG overexpression significantly reduced the number of tumor nodules in the lung tissues (P < 0.05; Figure S1F). However, MIR22HG knockdown promoted the metastasis of HCC-LM3 cells to lungs (Figure S3B, S3C). Collectively, these data indicated that MIR22HG repressed HCC cell invasion and metastasis.

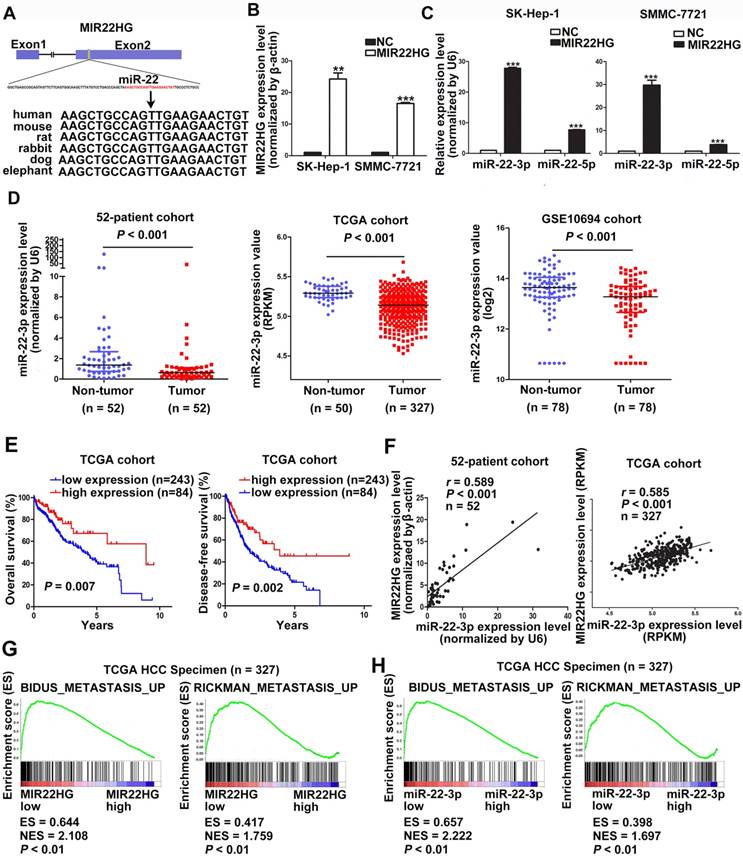

MIR22HG Inhibits Cell Invasion via miR-22-3p

The high degree of conservation of the miR-22-containing region of MIR22HG among mammals implied an important role for miR-22 (Figure 3A). Overexpression of MIR22HG markedly increased miR-22-3p expression level in SMMC-7721 and SK-Hep-1 cells (Figure 3B, 3C), whereas MIR22HG downregulation significantly reduced miR-22-3p expression in HCC-LM3 cells (Figure S4A). To determine the clinical significance of this miRNA, we analyzed miR-22-3p expression in the 52-patient, TCGA, and GSE10694 cohorts. The results showed that miR-22-3p was significantly downregulated in HCC tissues as compared with non-tumor tissues (Figure 3D; P< 0.001 for all three cohorts). Furthermore, miR-22-3p expression was significantly associated with both OS and DFS in HCC patients (P = 0.007 for OS; P = 0.002 for DFS; Figure 3E).

We subsequently evaluated whether the aberrant MIR22HG and miR-22-3p expression was correlated in HCC. A significant positive correlation was found in the 52-patient (r = 0.589; P< 0.001) and TCGA (r = 0.585; P< 0.001) cohorts (Figure 3F). Together, these results demonstrated that MIR22HG was positively correlated with miR-22-3p in HCC.

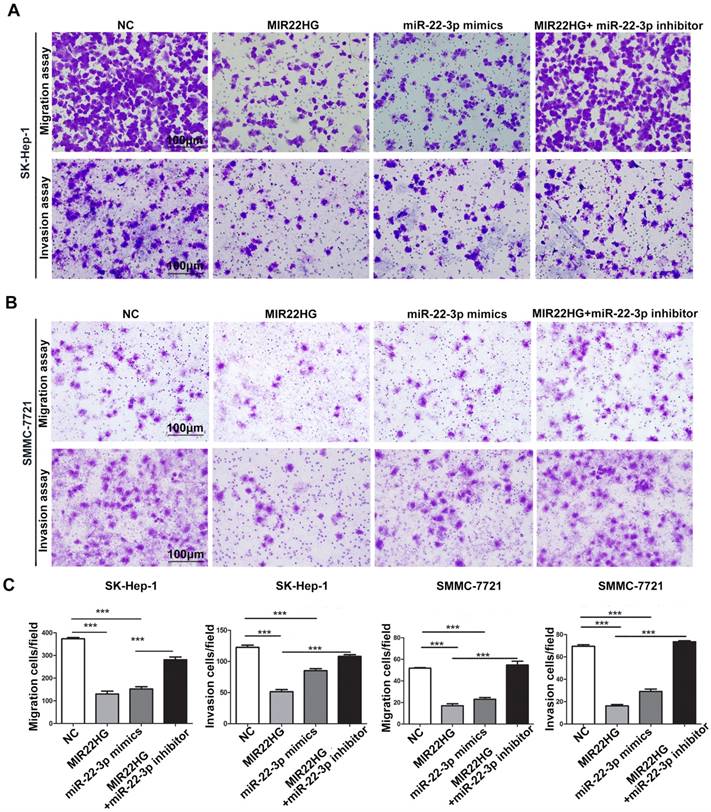

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the TCGA cohort demonstrated that the expression of both MIR22HG and miR-22-3p was inversely correlated with gene signatures of metastasis (Figure 3G, 3H). This suggests that MIR22HG and miR-22-3p have a concordant function in HCC metastasis. Additionally, in vitro migration and invasion assays indicated that cell mobility and invasiveness were impaired by miR-22-3p overexpression, but promoted by miR-22-3p inhibition (Figure S4B-D). Furthermore, repression of miR-22-3p expression in MIR22HG-overexpressing SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells showed that miR-22-3p inhibition rescued the migration and invasion capabilities decreased by MIR22HG overexpression (Figure 4 and Figure S5A). Conversely, miR-22-3p upregulation suppressed the promotion of migration and invasion by MIR22HG knockdown in HCC-LM3 cells (Figure S5B, S5C). Therefore, our data indicated that MIR22HG played a suppressor role in HCC via miR-22-3p.

HMGB1, a Direct Target of miR-22-3p, is Crucial for the Function of MIR22HG

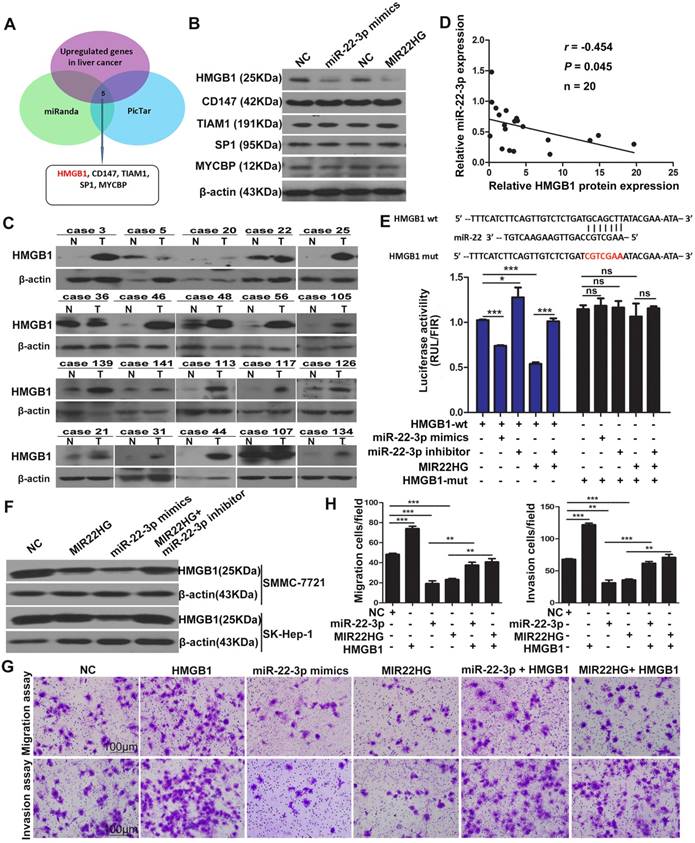

To investigate the targets of miR-22-3p regulated by MIR22HG, we performed bioinformatics analysis using the miRanda and picTar algorithms and found a set of potential target genes of miR-22-3p (Table S4). Overlapping these genes with those up-regulated in liver cancer (GSE14520 and GSE6762 dataset) yielded 5 candidate genes, including HMGB1, cluster of differentiation 147(CD147), T cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1(TIAM1), SP1, and c-MYC-binding protein (MYCBP) (Figure 5A). However, expression analysis showed that only the HMGB1 protein was downregulated in SMMC-7721 cells upon miR-22-3p or MIR22HG overexpression (Figure 5B and Figure S6A-C). Correlation analysis showed that the relative expression of the HMGB1 protein was negatively correlated with miR-22-3p expression in 20 HCC samples (r = -0.454; P = 0.045; Figure 5C, 5D, and Figure S6D). These findings indicated that HMGB1 might represent a target of miR-22-3p in HCC.

MIR22HG is positively associated with miR-22-3p in HCC. (A) Human miR-22 is located in exon 2 of the MIR22HG gene. miR-22-3p is conserved between humans, mice, rats, rabbits, dogs, and elephants. (B) MIR22HG expression level was detected in MIR22HG-overexpressing SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells by qRT-PCR. (C) miR-22-3p and miR-22-5p expression levels in MIR22HG-overexpressing SK-Hep-1 and SMMC-7721 cells. U6 was used as an internal control. Data are shown as median with interquartile range. ***P< 0.001; ***P< 0.0001. (D) miR-22-3p expression in the 52-patient, TCGA, and GSE10694 cohorts (P < 0.001). (E) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall and disease-free survival in the TCGA cohort based on miR-22-3p expression. (F) Correlation of MIR22HG and miR-22-3p expression in the 52-patient and TCGA cohorts. Results of Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) were plotted to visualize the correlation between the expression of MIR22HG (G) or miR-22-3p (H) and gene signatures of metastasis in the TCGA cohort (P < 0.01).

To verify the direct interaction between miR-22-3p and HMGB1, the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of HMGB1 was cloned into a luciferase reporter vector (psiCHECK-wt-HMGB1), which was transfected into SMMC-7721 cells together with an miR-22-3p mimic. To exclude non-specific binding, we mutated the miR-22-3p-binding site of the 3′ UTR of HMGB1 to generate the psiCHECK-mut-HMGB1 vector. Luciferase reporter assays showed that miR-22-3p mimic transfection significantly reduced the luciferase activity of psiCHECK-wt-HMGB1, but had no effect on the activity of psiCHECK-mut-HMGB1 (Figure 5E). Additionally, the results showed that transfection with an miR-22-3p inhibitor led to increased luciferase activity (Figure 5E). These data indicated that HMGB1 is directly targeted by miR-22-3p.

miR-22-3p mediates the inhibitory effect of MIR22HG on the migration and invasion of HCC cells. Representative images (A-B) and quantification (C) of migration and invasion assays of the indicated cell lines following overexpression of MIR22HG or miR-22-3p alone or with the addition of a miR-22-3p inhibitor. Each bar represents the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.0001, ns: not significant.

We then evaluated whether HMGB1 is regulated by MIR22HG. Luciferase assays showed that MIR22HG overexpression significantly reduced the luciferase activity of psiCHECK-wt-HMGB1; however, this effect was rescued by applying the miR-22-3p inhibitor (Figure 5E), indicating that MIR22HG produced miR-22-3p to bind the 3′ UTR of HMGB1. Furthermore, HMGB1 expression was decreased upon MIR22HG overexpression and increased following MIR22HG knockdown in HCC cells (Figure 5F and Figure S6E). Conversely, HMGB1 expression was restored in MIR22HG-overexpressing cells treated with miR-22-3p inhibitor (Figure 5F) as well as in MIR22HG-silenced cells transfected with the miR-22-3p mimic (Figure S6E). Additionally, the expression of the HMGB1 downstream effectors MMP9 and p-ERK was also altered concomitant with miR-22-3p and MIR22HG overexpression (Figure S6F), suggesting a regulatory effect of MIR22HG and miR-22-3p on HMGB1 expression and its downstream pathway. Furthermore, restoration of HMGB1 expression abrogated the inhibitory effect of MIR22HG or miR-22-3p on mobility and invasion in HCC cells, suggesting that HMGB1 mediated the function of MIR22HG and miR-22-3p. (Figure 5G, 5H). Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of sections of xenograft tumor demonstrated that HMGB1 was expressed at low levels in MIR22HG-overexpressing xenografts as compared with control tumors, demonstrating that HMGB1 is regulated by MIR22HG in vivo (Figure S6G).

HMGB1 is regulated by MIR22HG in HCC. (A) Schematic diagram of the protocol used to search for candidate genes regulated by miR-22-3p. (B) Protein levels of HMGB1, CD147, TIAM1, SP1, and MYCBP in SK-Hep-1 cells overexpressing miR-22-3p or MIR22HG as detected by western blotting. (C) Western blot of HMGB1 protein levels in 20 tumor (T) and non-tumor (N) tissues. (D) Correlation between miR-22-3p and HMGB1 protein expression in 20 HCC tissues (P = 0.045). (E) Top: diagram of miR-22-3p putative binding sites in the 3′ UTR of HMGB1. The mutant sequences used in the luciferase reporters are indicated in red. Bottom: The luciferase expression vectors psiCHECK-wt-HMGB1 and psiCHECK-mut-HMGB1 were co-transfected with a miR-22-3p mimic, miR-22-3p inhibitor, or MIR22HG vector, followed by measurement of the luciferase activities. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.0001, ns: not significant. (F) Protein level of HMGB1 as detected by western blotting in SMMC-7721 and SK-Hep-1 cells overexpressing miR-22-3p, MIR22HG, or MIR22HG plus a miR-22-3p inhibitor. (G-H) Representative images of migration and invasion assays of the indicated cell lines. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

HuR Mediates the Functionality of MIR22HG

To identify whether the function of MIR22HG was entirely dependent upon miR-22-3p, we mutated the miR-22-3p region of MIR22HG to generate the MIR22HG-mut vector and established stable HCC cells overexpressing mutant MIR22HG (Figure S7A). The expression of miR-22-3p was increased upon wild-type MIR22HG overexpression, but not following mutant MIR22HG overexpression (Figure S7A). Additionally, mutant MIR22HG significantly impaired the proliferation, migration, and invasion capacities of SMMC-7721 cells (P < 0.01; Figure S7B, S7C). However, the inhibitory effect of mutant MIR22HG was weaker than that of wild-type MIR22HG (P < 0.01; Figure S7B, S7C), which indicated that MIR22HG plays its suppressor role in part through miR-22-3p.

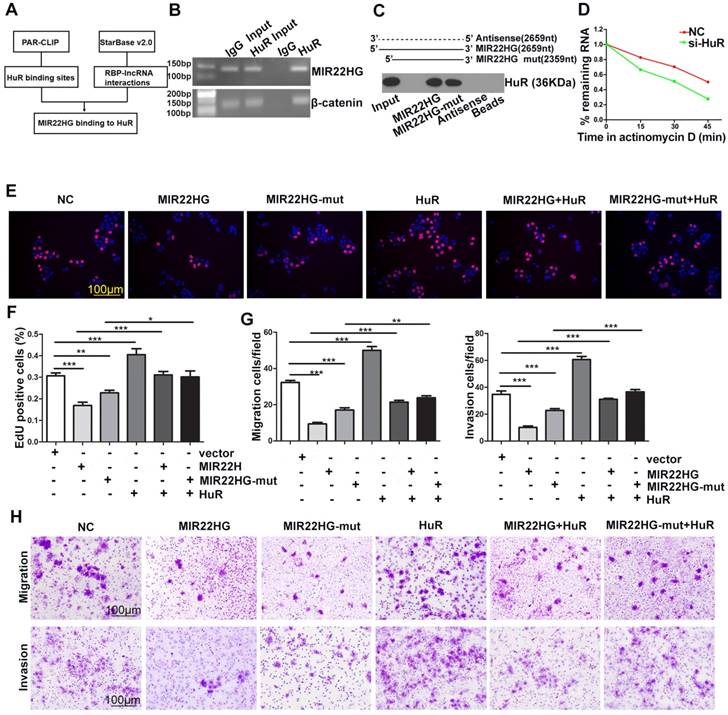

HuR binds to MIR22HG and increases its stability. (A) Bioinformatics analysis using HuR photoactivatable-ribonucleotide-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP, GSE 28865) analysis and StarBase v2.0 software. (B) RIP assay of HuR and MIR22HG binding in SMMC-7721 cells. CTNNB1 (β-catenin) was used as a positive control. (C) RNA pull-down assay showed that both MIR22HG and MIR22HG-mut interacted with HuR. (D) Effect of HuR knockdown on the half-life of MIR22HG. (E-F) Effect of MIR22HG and MIR22HG-mut alone or with HuR on cell proliferation as measured by EdU assays. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001. (G-F) In vitro migration and invasion assays showing the effects of overexpression of MIR22HG and MIR22HG-mut alone or with HuR on cellular migration or invasion abilities. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

The results of ISH (Figure 1D) and cytoplasmic and nuclear RNA fraction assays (Figure S7D) demonstrated that MIR22HG was mainly located in the cytoplasm of HCC cells and tissues. Bioinformatics analysis using HuR photoactivatable-ribonucleotide-enhanced cross-linking, immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP; GSE28865) analysis and StarBase software v2.0 (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/rbpLncRNA.php) predicted that MIR22HG might interact with the HuR protein (Figure 6A). Accordingly, an RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay confirmed a direct binding relationship between MIR22HG and HuR (Figure 6B), and RNA pull-down assay further confirmed the interaction of both MIR22HG and MIR22HG-mut with HuR (Figure 6C). Furthermore, HuR knockdown significantly decreased MIR22HG expression by shortening the half-life of MIR22HG in SMMC-7721 cells (Figure 6D and Figure S7E, S7F). This phenomenon demonstrated that HuR bound and stabilized the MIR22HG RNA. To gain further insight into the relationship between HuR and MIR22HG, we first detected HuR mRNA and MIR22HG expression in HCC tissues. As shown in Figure S7G, no significant correlation was found between HuR mRNA and MIR22HG expression (P = 0.334; r = 0.033). Consistently, weak correlations were also observed between the expression of these two genes following analysis of expression data from GSE14520 (Figure S7H, P = 0.013, r = 0.023). We then examined HuR protein expression levels in HCC tissues. Interestingly, in HCC tissues with higher HuR protein expression, MIR22HG was found to be expressed at high levels, although the expression of MIR22HG still remained low in HCC tissues as compared with non-tumor tissues (Figure S7I, S7J). Additionally, HuR overexpression reversed the wild-type or mutant MIR22HG-mediated suppression of proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCC cells (Figure 6E-H), suggesting that HuR mediated the function of MIR22HG in HCC cells.

HuR can directly bind and control the functions of a subset of mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs [19-22]. The effect of HuR is modulated in part through adjustment of HuR abundance. Notably, we found that overexpression of wild-type or mutant MIR22HG induced translocation of HuR from the cytoplasm to the nucleus in SMMC-7721 cells (Figure S8A, S8B). Furthermore, MIR22HG deletion induced HuR translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm in HCC-LM3 cells (Figure S8C, S8D). This indicated that MIR22HG could regulate the subcellular localization of HuR and decrease its cytoplasmic abundance.

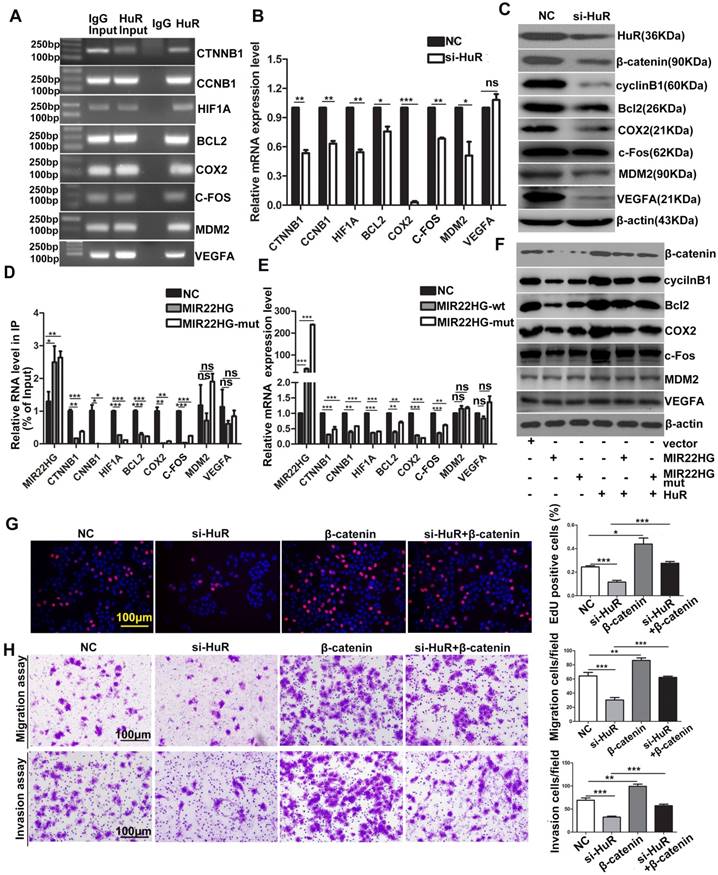

HuR targets include many oncogenic mRNAs such as CTNNB1, CCNB1, HIF1A, BCL2, COX2, MDM2 (encoding mouse double-minute-2 homolog MDM2), VEFGA (encoding vascular endothelial growth factor A) and C-FOS that encode proteins involved in cellular proliferation, invasion, and metastasis [23, 24]. The RIP assays confirmed that HuR directly bound to these mRNAs (Figure 7A), and HuR knockdown significantly reduced the mRNA and/or protein levels of β-catenin, HIF-1α, cyclinB1, Bcl2, COX2, MDM2, VEGFA and c-Fos (Figure 7B, 7C), indicating that HuR influenced the stability and/or translation of these genes. We then investigated whether MIR22HG affected the interaction between HuR and these oncogenes. RIP assays demonstrated that in the presence of MIR22HG, a marked increase in binding was observed between MIR22HG and HuR, which thereby reduced the binding capabilities of HuR to the oncogenes including CTNNB1, CCNB1, HIF1A, BCL2, COX2, and C-FOS (Figure 7D), but not MDM2 and VEGFA. Accordingly, both mRNA and protein levels of β-catenin, HIF-1α, cyclinB1, Bcl2, COX2, and c-Fos were dramatically reduced in cells overexpressing wild-type or mutant MIR22HG (Figure 7E, 7F), but highly induced in MIR22HG-silencd cells (Figure S9A, S9B), indicating that MIR22HG competed with these oncogenes to bind HuR. miR-22-3p targets various genes in diverse cancer type. Here, the expression of β-catenin, HIF-1α, cyclinB1, Bcl2, COX2, and c-Fos was examined in SMMC-7721 cells transfected with an miR-22-3p mimic or inhibitor to determine whether MIR22HG inhibited the upper genes via miR-22-3p. The results showed that miR-22-3p did not alter the expression of the indicated genes (Figure S9C, S9D), suggesting that MIR22HG downregulated the indicated genes independent of miR-22-3p. Additionally, overexpression of wild-type or mutant MIR22HG reversed the oncogene up-regulation caused by HuR overexpression (Figure 7F), suggesting that MIR22HG could inhibit the effect of HuR on these oncogenes. Moreover, overexpression of these oncogenes blocked the effect of HuR knockdown in HCC cells, as demonstrated using β-catenin (Figure 7G, 7H). Collectively, our data suggested that HuR might play a critical role in MIR22HG-mediated tumor suppression.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this represents the first study to investigate the biological function of MIR22HG in cancer. We presented strong evidence that MIR22HG is expressed at low levels in HCC tissues as compared with non-tumor liver tissues based on 4 cohorts. Our results showed that low MIR22HG expression correlated with tumor progression, and that MIR22HG expression represented an independent predictor of prognosis in HCC patients. Functionally, MIR22HG overexpression repressed tumor cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis. Therefore, our data indicated that MIR22HG expression serves as a decisive factor for controlling human HCC progression.

Numerous studies demonstrated the complicated relationship between miRNAs and their host genes, and that each might be subject to different regulatory mechanisms under different circumstances. For example, miR-579 targets its host gene zinc finger RNA-binding protein (ZFR) by binding the 3′UTR, whereas simultaneously it also targets the 3′-UTR-processing factor CPSF2, thereby leading to changes in the 3′UTR of ZFR and decoupling of the negative feed-back circuitry [25]. miR-11 directly represses the expression of Drosophilia rpr and hid, which are transcriptionally up-regulated by the miR-11 host gene dE2F1 [26]. In our study, both miR-22-3p and its host gene MIR22HG were down-regulated in HCC, whereas high expression of either strongly correlated with the beneficial prognosis of HCC patients. We also found that MIR22HG expression was positively associated with that of miR-22-3p in HCC, consistent with results associated with leukemia and breast cancer, although the number of tumors analyzed was smaller in the other studies [27, 28].

MIR22HG and MIR22HG-mut influence the binding of HuR to its target mRNA. (A) RIP assays indicating the binding of HuR to CTNNB1, CCNB1, HIF1A, BCL2, COX2, MDM2, VEGFA and C-FOS. (B) qRT-PCR assay showing the effects of HuR knockdown on the mRNA expression levels of the indicated genes. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001. (C) Effect of HuR knockdown on the expression of the indicated proteins. (D) Effect of MIR22HG or MIR22HG-mut overexpression on HuR binding with the indicated mRNAs according to RIP assays. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001. (E) Effect of MIR22HG or MIR22HG-mut overexpression on the expression of the indicated mRNAs. ***P < 0.0001. (F) Effect of MIR22HG and sMIR22HG-mut overexpression or either of these in the presence of HuR on the expression of the indicated proteins. (G, H) Effects of HuR silencing alone or with β-catenin on (G) cell proliferation, as detected by EdU assays or (H) cell migration and invasion, as detected by in vitro migration and invasion assays. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.0001.

Furthermore, the expression of miR-22-3p and its target gene (HMGB1) was altered by both MIR22HG overexpression and knockdown, indicating that they are functionally related. In HCC cells, MIR22HG and miR-22-3p repressed migration and invasion by inhibiting HMGB1. Additionally, miR-22-3p inhibition or HMGB1 overexpression were able to reverse the suppressive effect of MIR22HG on these processes. Together, these data demonstrated that MIR22HG and miR-22-3p were co-expressed and functionally coordinated.

Notably, mutation of MIR22HG in the miR-22-3p region demonstrated that the mutant MIR22HG retained the ability to inhibit HCC cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. This indicated that the function of MIR22HG was not totally dependent upon the derived miR-22-3p. Investigation of the molecular mechanisms involved in MIR22HG contributing to tumor suppression identified the involvement of HuR, which regulated the splicing, stability, or translation of thousands of coding and non-coding RNAs [19, 29]. Our data showed that HuR also regulated the stability of MIR22HG and mediated the function of MIR22HG in HCC.

We also found that HuR stabilized many oncogenic mRNAs, including CTNNB1, CCNB1, HIF1A, BCL2, COX2 and C-FOS, consistent with previous studies [24, 29-31]. However, decrease in the mRNA or protein levels of β-catenin, cyclinB1, HIF1A, Bcl2, COX2 and c-Fos in wild-type or mutant MIR22HG-overexpressing cells indicated that MIR22HG preferentially bound to HuR and decreased the expression of these oncogenes. Furthermore, our data demonstrated that MIR22HG competed with these oncogenic mRNAs, thereby influencing their affinity with HuR. In this context, HuR mediated the stabilization of the tumor suppressor MIR22HG, thereby destabilizing many oncogenes.

Cumulative research shows that an aberrant nucleus/cytoplasm ratio of HuR correlates with tumor initiation and development [32, 33]. Cytoplasmic HuR accumulation is associated with unfavorable clinical outcomes in patients with malignant diseases, such as breast cancer, esophageal cancer, lung cancer, and bladder carcinoma [34-37]. In the present study, we found that MIR22HG regulated HuR subcellular localization, and that overexpression of wild-type or mutant MIR22HG promoted the translocation of HuR from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Therefore, our data indicated that although HuR represents an attractive target for cancer treatment, in some cases, the presence of HuR is necessary for the stabilization of certain tumor suppressors.

In summary, our data demonstrated that MIR22HG was negatively correlated with HCC progression and prognosis. MIR22HG suppressed HCC cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by deriving miR-22-3p and competitively binding HuR, leading to the downregulation of multiple oncogenes and deactivation of HMGB1 signaling (Figure S10). We also found that MIR22HG could regulate the HuR subcellular localization. Our findings support that understanding the key roles of lncRNA modules in HCC will likely lead to identification of new therapeutic targets for treating HCC.

Materials and Methods

Human HCC Samples

“52-patient cohort”: HCC samples and paired noncancerous specimens from 52 HCC patients who underwent hepatectomies between January 2012 and January 2013 at Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China) were included in this study. Tissues were frozen with liquid nitrogen instantly after hepatectomies and stored in a refrigerator at -80ºC. Patient clinical information is listed in Table S1.

“145-patient cohort”: Randomly selected paraffin-embedded tissues from 145 HCC patients who underwent resection of liver cancer between January 2006 and July 2009 were obtained from the Department of Pathology of the same hospital. Neither chemotherapy nor radiotherapy was used as a treatment for these HCC patients before curative resection. The patients were followed-up for 5 years. Patient information is shown in Table S2. Criteria proposed by Edmonson and Steiner were used to determine tumor differentiation. Tumor staging was defined according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system.

Informed consent was acquired from patients in the 52- and 145-patient cohorts. The study was reviewed and approved by the Nanfang Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Cell Lines

HL-7702, MHCC-97H, SK-Hep-1, HepG2, SMMC-7721, Huh7, and HCC-LM3 cells were obtained from the Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection (Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China). Cells were cultured under the conditions provided by the supplier.

Animal Studies

A subcutaneous xenograft model was established to estimate the effect of MIR22HG on tumor growth in vivo. BALB/c nude mice (males, 4-5-weeks-old) were purchased from the Central Laboratory of Animal Science, Southern Medical University (Guangzhou, China). Experimental procedures in this study were performed according to our institutional guidelines for using laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanfang Hospital. In total, 1 × 107 SMMC-7721, SK-Hep-1 or HCC-LM3 cells stably expressing MIR22HG or sh-MIR22HGand vector control were subcutaneously injected into the bilateral flanks of the mice. Prior to injection, the cells were transfected with pCMV-luciferase (Genechem Company Ltd., Shanghai, China). After 30 days, the fluorescence intensity in the tumor was detected using an IVIS@ Lumina II system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA) before the mice were sacrificed. Tumors were weighed after removal, and tumor tissues were embedded in paraffin for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemical (IHC) staining.

An extra-hepatic metastasis model was established to explore the effects of MIR22HG on extra-hepatic metastasis. In total, 3 × 106 SK-Hep-1 or HCC-LM3 cells were intravenously injected into the mice via tail veins. Prior to injection, the cells were transfected with pCMV-luciferase. After 6 (SK-Hep-1 cells) or 3 weeks (HCC-LM3 cells), fluorescence intensity in the lungs was examined and the mice were sacrificed. The lung tissues were embedded in paraffin for H&E and IHC staining.

Gene-expression Datasets

“TCGA cohort”: A cohort from the TCGA (https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/) database including 327 HCC patients with MIR22HG or miR-22-3-expression data, as well as follow-up information, were included in our study to explore the expression levels of MIR22HG or miR-22-3p in HCC. A total of 50 cases among these patients included MIR22HG- or miR-22-3p-expression data for both HCC and paired non-tumor specimens. OS and DFS were also assessed according to MIR22HG- or miR-22-3p-expression level as follows: Patients were split into two groups on the basis of MIR22HG- or miR-22-3p- expression status in the primary tumor. Those with an MIR22HG- or miR-22-3p-expression level ranked in the top quartile were classified into the high expression group and the rest into the low expression group [38, 39].

“GSE14520 and 10694 cohorts”: Two sets of microarray data (GEO accession numbers GSE14520 [40] and GSE10694 [41]) were downloaded from the GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) to validate MIR22HG- or miR-22-3p-expression level in HCC. The GSE14520 (platform GPL3921, Affymetrix HT Human Genome U133A Array) dataset was utilized to analyze MIR22HG expression in HCC, and the GSE10694 (platform GPL6542, CapitalBio Mammalian miRNA Array Services V1) dataset was used for miR-22-3p expression level analysis in HCC.

GSEA

GSEA was performed to confirm which gene sets or signatures were correlated with MIR22HG or miR-22-3p expression in the TCGA dataset. The genome-wide expression profiles, including 377 samples, were downloaded from the TCGA dataset. Among these samples, a total of 327 with MIR22HG- or miR-22-3p-expression data were entered for GSEA after being split into two groups (MIR22HG low- or high-expression groups; miR-22-3p low- or high-expression groups). The GSEA software (GSEA v. 2.0, http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea) was utilized to test whether members of the gene sets or signatures were randomly distributed at the top or bottom of the ranking (genes from patients were ranked based on the correlation between miR-22-3p or MIR22HG expression). Once most members of a gene set were positively correlated with low expression of MIR22HG or miR-22-3p, the gene set was considered as having been correlated.

CCK-8 and EdU Assays, qRT-PCR, Plasmid Construction and Transient Transfection, Lentiviral Construction and Transduction, miRNA Transfection, Luciferase Reporter Assays, RNA Interference, In Situ Hybridization (ISH), Immunohistochemistry (IHC), Western Blot, RNA-Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation (RIP) Analyses, RNA Pull-Down Assay, Immunofluorescence Assay

These methods were performed as described previously and are detailed in Supplementary Material.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) from three separate experiments, except for a special annotation. The t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparison of two groups, multi-way classification ANOVA for cell proliferation, Pearson's correlation for analyzing the correlation between miR-22-3p and MIR22HG or HMGB1, Kaplan-Meier for survival analysis, and univariate and multivariate Cox regression for determining the independent factors of survival were used in this study. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). A P < 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81773008, 81672756, and 91540111), Guangdong Province Universities and Colleges Pearl River Scholar Funded Scheme (2015), and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2014A030311013, and 2017A030311023).

Abbreviations

ANOVA: one-way analysis of variance; BCLC: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CD147: cluster of differentiation 147; CI: confidence interval; DFS: Disease-free Survival; ENCODE: Encyclopedia of DNA Elements; GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus; GSEA: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HMGB1: high mobility group box 1; HuR: human antigen R; HR: hazard radio; ISH: in situ hybridization; IHC: Immunohistochemical; lncRNA: long non-coding RNA; MIR22HG: miR-22 host gene; MYCBP: c-MYC-binding protein; NC: Negative Control; OS: Overall Survival; PVTT: portal vein tumor thrombus; PAR-CLIP: HuR photoactivatable-ribonucleotide-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation; qRT-PCR: quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; RIP: RNA-binding protein immunoprecipitation; SEM: standard error of the means; TCGA: The Cancer Genome Atlas; TLAM1: T cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1; UTR: 3'-untranslated region.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials and methods, figures and tables.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108

2. Waghray A, Murali AR, Menon KN. Hepatocellular carcinoma: From diagnosis to treatment. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1020-9

3. Bodzin AS, Busuttil RW. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Advances in diagnosis, management, and long term outcome. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1157-67

4. Ding T, Xu J, Zhang Y, Guo RP, Wu WC, Zhang SD. et al. Endothelium-coated tumor clusters are associated with poor prognosis and micrometastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Cancer. 2011;117:4878-89

5. Zhang Y, Shi ZL, Yang X, Yin ZF. Targeting of circulating hepatocellular carcinoma cells to prevent postoperative recurrence and metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:142-7

6. Liz J, Esteller M. lncRNAs and microRNAs with a role in cancer development. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015

7. Beermann J, Piccoli MT, Viereck J, Thum T. Non-coding RNAs in Development and Disease: Background, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Approaches. Physiol Rev. 2016;96:1297-325

8. Lavorgna G, Vago R, Sarmini M, Montorsi F, Salonia A, Bellone M. Long non-coding RNAs as novel therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2016;110:131-8

9. Takahashi K, Yan I, Haga H, Patel T. Long noncoding RNA in liver diseases. Hepatology. 2014;60:744-53

10. Cao C, Sun J, Zhang D, Guo X, Xie L, Li X. et al. The long intergenic noncoding RNA UFC1, a target of MicroRNA 34a, interacts with the mRNA stabilizing protein HuR to increase levels of beta-catenin in HCC cells. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:415-26.e18

11. Zheng J, Xiong D, Sun X, Wang J, Hao M, Ding T. et al. Signification of Hypermethylated in Cancer 1 (HIC1) as Tumor Suppressor Gene in Tumor Progression. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:285-93

12. Zhao X, He M, Wan D, Ye Y, He Y, Han L. et al. The minimum LOH region defined on chromosome 17p13.3 in human hepatocellular carcinoma with gene content analysis. Cancer lett. 2003;190:221-32

13. Franca GS, Vibranovski MD, Galante PA. Host gene constraints and genomic context impact the expression and evolution of human microRNAs. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11438

14. Liu G, Xiang T, Wu QF, Wang WX. Long Noncoding RNA H19-Derived miR-675 Enhances Proliferation and Invasion via RUNX1 in Gastric Cancer Cells. Oncol Res. 2016;23:99-107

15. Guan GF, Zhang DJ, Wen LJ, Xin D, Liu Y, Yu DJ. et al. Overexpression of lncRNA H19/miR-675 promotes tumorigenesis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. IntJ Med Sci. 2016;13:914-22

16. Lv J, Wang L, Zhang J, Lin R, Wang L, Sun W. et al. Long noncoding RNA H19-derived miR-675 aggravates restenosis by targeting PTEN. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.011

17. Augoff K, McCue B, Plow EF, Sossey-Alaoui K. miR-31 and its host gene lncRNA LOC554202 are regulated by promoter hypermethylation in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:5

18. Farhana L, Antaki F, Anees MR, Nangia-Makker P, Judd S, Hadden T. et al. Role of cancer stem cells in racial disparity in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5:1268-78

19. Abdelmohsen K, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional regulation of cancer traits by HuR. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2010;1:214-29

20. Legnini I, Morlando M, Mangiavacchi A, Fatica A, Bozzoni I. A feedforward regulatory loop between HuR and the long noncoding RNA linc-MD1 controls early phases of myogenesis. Mol Cell. 2014;53:506-14

21. Noh JH, Kim KM, Abdelmohsen K, Yoon JH, Panda AC, Munk R. et al. HuR and GRSF1 modulate the nuclear export and mitochondrial localization of the lncRNA RMRP. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1224-39

22. Pang L, Tian H, Chang N, Yi J, Xue L, Jiang B. et al. Loss of CARM1 is linked to reduced HuR function in replicative senescence. BMC Mol Biol. 2013;14:15

23. Kotta-Loizou I, Giaginis C, Theocharis S. Clinical significance of HuR expression in human malignancy. Med Oncol. 2014;31:161

24. Dormoy-Raclet V, Cammas A, Celona B, Lian XJ, van der Giessen K, Zivojnovic M. et al. HuR and miR-1192 regulate myogenesis by modulating the translation of HMGB1 mRNA. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2388

25. Hinske LC, Galante PA, Limbeck E, Mohnle P, Parmigiani RB, Ohno-Machado L. et al. Alternative polyadenylation allows differential negative feedback of human miRNA miR-579 on its host gene ZFR. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121507

26. Truscott M, Islam AB, Lopez-Bigas N, Frolov MV. mir-11 limits the proapoptotic function of its host gene, dE2f1. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1820-34

27. Patel JB, Appaiah HN, Burnett RM, Bhat-Nakshatri P, Wang G, Mehta R. et al. Control of EVI-1 oncogene expression in metastatic breast cancer cells through microRNA miR-22. Oncogene. 2011;30:1290-301

28. Wang J, Xiang G, Zhang K, Zhou Y. Expression signatures of intragenic miRNAs and their corresponding host genes in myeloid leukemia cells. Biotechnol Lett. 2012;34:2007-15

29. Kim J, Abdelmohsen K, Yang X, De S, Grammatikakis I, Noh JH. et al. LncRNA OIP5-AS1/cyrano sponges RNA-binding protein HuR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:2378-92

30. Fernandez-Ramos D, Martinez-Chantar ML. NEDDylation in liver cancer: The regulation of the RNA binding protein Hu antigen R. Pancreatology. 2015;15(Suppl 4):S49-54

31. Chou SD, Murshid A, Eguchi T, Gong J, Calderwood SK. HSF1 regulation of beta-catenin in mammary cancer cells through control of HuR/elavL1 expression. Oncogene. 2015;34:2178-88

32. Govindaraju S, Lee BS. Adaptive and maladaptive expression of the mRNA regulatory protein HuR. World J Biol Chem. 2013;4:111-8

33. Gauchotte G, Hergalant S, Vigouroux C, Casse JM, Houlgatte R, Kaoma T. et al. Cytoplasmic overexpression of RNA-binding protein HuR is a marker of poor prognosis in meningioma, and HuR knockdown decreases meningioma cell growth and resistance to hypoxia. J Pathol. 2017;242:421-34

34. Yuan Z, Sanders AJ, Ye L, Jiang WG. HuR, a key post-transcriptional regulator, and its implication in progression of breast cancer. Histol Histopathol. 2010;25:1331-40

35. Zhang C, Xue G, Bi J, Geng M, Chu H, Guan Y. et al. Cytoplasmic expression of the ELAV-like protein HuR as a potential prognostic marker in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:73-80

36. Giaginis C, Alexandrou P, Tsoukalas N, Sfiniadakis I, Kavantzas N, Agapitos E. et al. Hu-antigen receptor (HuR) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in human non-small-cell lung carcinoma: associations with clinicopathological parameters, tumor proliferative capacity and patients' survival. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:315-27

37. Guo J, Lv J, Chang S, Chen Z, Lu W, Xu C. et al. Inhibiting cytoplasmic accumulation of HuR synergizes genotoxic agents in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Oncotarget. 2016;7:45249-45262

38. Hou Z, Zhao W, Zhou J, Shen L, Zhan P, Xu C. et al. A long noncoding RNA Sox2ot regulates lung cancer cell proliferation and is a prognostic indicator of poor survival. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53:380-8

39. Gomez-Maldonado L, Tiana M, Roche O, Prado-Cabrero A, Jensen L, Fernandez-Barral A. et al. EFNA3 long noncoding RNAs induced by hypoxia promote metastatic dissemination. Oncogene. 2015;34:2609-20

40. Roessler S, Long EL, Budhu A, Chen Y, Zhao X, Ji J. et al. Integrative genomic identification of genes on 8p associated with hepatocellular carcinoma progression and patient survival. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:957-66.e12

41. Li W, Xie L, He X, Li J, Tu K, Wei L. et al. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of microRNAs in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1616-22

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Prof. D. Wu, Department of Radiation Oncology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China. Tel: 86-20-62787693; Fax: 86-20-62787631. E-mail: wudehua.gdcom or Prof. L. Liu, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Viral Hepatitis Research, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China. E-mail: liuli.fimmucom.

Corresponding authors: Prof. D. Wu, Department of Radiation Oncology, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China. Tel: 86-20-62787693; Fax: 86-20-62787631. E-mail: wudehua.gdcom or Prof. L. Liu, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Viral Hepatitis Research, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, China. E-mail: liuli.fimmucom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact